Michael Adno is an artist and writer based in New York City, born in Florida as a first generation American. He works as a contributing editor for At Large magazine. His work has appeared in Oxford American, The Surfer’s Journal, Camera Austria, SRQ, Huck, OZY, and Autre magazines among others. During the last year, he was a fellow at the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation, a resident in the Lower East Side Printshop’s Keyholder Residency, and a finalist for the Smithsonian’s Artist Research Fellowship. He just finished a long form piece on the restoration of the Everglades, and he’ll be a fellow at Hermitage Artist Retreat later this year. Recently I asked Michael a few questions about his work and his passion for photography.

Memories Lounge, North Sarasota, Florida, 2016

After reading the text you sent me about the work, I couldn’t help but think this is the perfect for a detective / murder mystery novel. Are you approaching this subject matter as a detective of sorts? Do you think this makes it more fun or engaging for you as an artist to keep probing deeper into this subject?

Yeah, sometimes I think it can seem a bit clandestine. And to that point, I mean a lot of bits and bobs that make up the historical record happen to be clandestine, politics, folklore, and so forth. And to the mystery, detective tinge, I’d say sure, but it’s just what’s on the surface. I’ve worked with two people closely in the field (Matt Town and Jordan Blumetti) who were not particularly familiar with the more out of the way places in Florida, and they both felt that way. It’s hard not to project upon a double-wide trailer set back a quarter mile in the pine scrubs. Add a full yard of detritus, children’s toys, and an assortment of vehicles, and you might think True Detective etc. At the end of the day though, that’s just ruin porn, misguided assumptions about place, and I hope that my work and others’ works against that. And sure sometimes, you do meet people who fit within the archetype of backwoods hicks, but the most interesting of people are those who challenge that understanding, that banal platitude of what it means to be southern. There’s a number of artists and writers who work against that, from James Agee, William Christenberry, William Eggleston, Sally Mann, Zora Neale Hurston, Stetson Kennedy. The list goes on and on. But for some reason, we as audience tend to prefer those wildly romantic notions of the South. Hell, I often do.

As to my approach, definitely. I mean I see it as more akin to longform, investigative journalism. And for the past few years, my work kept edging closer and closer to that approach, so inevitably I started writing, and I never could have predicted that. In fact, I probably would have been reluctant to the suggestion. I would never have guessed that I’d be making photographs or working as an artist either. Never!

For me, I want to work with something for a while. All the things that I take up become an obsession. I have no trouble seeing this project or this subject making up the breadth of what I work towards over my lifetime. It comforts me actually, which might be a problem. In the esoteric art speak lexicon, we refer to that as “project based practice,” but that’s obviously wildly vague and open-ended. For me, I just privilege long term investment, and I recognize that in the work of artists and writers whom I admire dearly. My dream would be to have the opportunity to show my work in a number of ways, continually engage in a more public dialogue, and to write for national outlets about the same things I’m looking for with a camera. My practice of making photographs wed to writing is the ultimate goal.

Clear-cut near Interlachen, Florida, 2016

Brown-Stallings’ Home, Little Orange Lake, Florida, 2016

The name Cracker Politics is bold and a little jarring, how did you decide on this title?

Well, I began the project working heavily in archives, everything from the Library of Congress to small unremarked historical societies. And at that point, I was interested in this idea of the way in which the colonial record fashions or molds our understanding of history hence, “The Limits of Colonial Knowledge.” The title “Cracker Politics” though has just continually updated itself and enveloped the categories of my project over the past three years, so I’m sticking with it. Cracker is known as a derogatory term for white people generally, its etymology evades any definitive point though. The origin stories are really interesting, everything from the noise of a cow whip cracking to the diet of poor white settlers. In Florida, Cracker culture was an agrarian culture made up of pioneers and settlers in the late eighteenth century up until the territory became a state. That whole period of subsisting on the land, taming the wild in so much as to live comfortably in the territory undoubtedly make up the contemporary psyche of the modern day Florida Cracker, sometimes redneck, sometimes ranch hand, sometimes intimidatingly intelligent persons whom live forty minutes from a stop light. And that’s to say that the every day politics of Florida natives derives from this time long long ago when your worth was less about monetary wealth or modern notions of success but the ownership of land, the cultural capital of subsisting on swamp cabbage, crops, and a constant back and forth with the environment. And that persists, for that sub-strata of Floridians and Southerners, and just rural folks generally. For some its just a part of every day life in which in order to maintain a parcel of land, species like the Spanish boar have to be eradicated among other invasive species. I should add that I don’t mean to lionize that culture as it was just as volatile and brutal as it was admirable. To your next question, these were the days of fair-weather death over broken social contracts and regrettable words. The one thread I always come back to with Cracker culture is this relationship to land. Think about how cherished and coveted private property is in the South. Unfortunately, that cherished land is in some cases kept private from those who seek to protect it and from those who want to elucidate all the history in its soil. So next time you hear some nearly intelligible, machismo saturated declaration from some redneck, think back to the time of the Cracker. It might make it a bit more palatable.

Janis and Bonita’s Office, Historical Society, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

What is one of the most interesting / unbelievable rumors or stories that you have learned during your investigation into this subject matter?

I’ve heard stories of mass genocide pertaining to the Spanish settlers, of Andrew Jackson lynching men for selling goods to Indians and people of color in Palatka, and hell have you ever heard of the Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida, the lynching of Claude Neal, Stetson Kennedy penetrating the Ku Klux Klan? John Baumgardner’s boot from the conventional Ku Klux Klan for being too radical? Rosewood, Florida? How about our Governor Rick Scott? The relationship between big agriculture and all tiers of political office are mind boggling. Pick up a Zora Neale Hurston anthology, Peter Matthiessen’s Shadow Country. I mean to say that truth is stranger than fiction. It’s fitting that a southerner, Mark Twain, should be the origin of that idiom. I think the idea that people still meet in groups to burn crosses in the annals of wooded properties is often unbelievable to people. And while that diminishing group of white supremacists seems less and less dangerous, just take a look at stormfront.org for some fodder. Take a look at the FBI’s field offices based in Northern Florida or the Southern Poverty Law Center’s hate map. Last year, three Florida corrections officers were arrested by the FBI for conspiracy to commit murder. They belonged to the Keystone Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. I could literally list pages of documented, recorded, real events that would trouble, confuse, and ultimately dull your sense of surprise but they go unreported. Of course, there are countless stories that are as encouraging, warm, and uplifting as those that are troubling.

Did it prove to be true?

Yes. Some of the stories that I’ve heard from a litany of locals are true. What’s funny is that I’ve noticed how people tend to be more compelled by fictional accounts and stories shrouded in mystery than clear historical records, but like I said I do truly believe truth is stranger than fiction. Clichés and age-old adages have a bit more depth than we tend to notice right? I think it’s the role of the artist or writer to draw out those kernels.

Georgia-Pacific Plant near Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

North Jetty Fish Camp, Nokomis, Florida, 2016

Site of Moses Levy’s Pilgrimage Plantation near Wacahoota, Florida, 2016

John, Micanopy, Florida, 2016

What has your family said about this work? Are they equally as curious as you are?

Hmmmm. This one gives me pause. Well first of all, my family is tiny. My mother and step father live here in the states. My father lived in South Africa and passed away last year. Other than that, I have a few cousins, an aunt, an uncle, and a lovely grandmother. And they are spread across the world, South Africa, Austria, and elsewhere. I’m also not from an intellectual or particularly creative family. Neither of my parents went to college, and when I was growing up (for the most part in Florida) we did not visit museums, think or talk about art. So just at its outset, they are a bit in the deep end. My mom is incredibly supportive. She’s the sole reason I graduated high school, moved to New York, and I wouldn’t have a damn thing without her. She’s a bit skeptical and neurotically worried at times. She’s on edge when I go out on trips to work, but that’s not unordinary of course. She’s my unparalleled Jewish mother. My dad never really had the chance to engage with the work, but he was the most supportive person of me pursuing art when I was in college. I wouldn’t have taken the loans to attend school in New York if he hadn’t told me to go. It felt downright stupid and indescribably impossible then. My dad and I always had a really healthy relationship as far as political discussion went. We were diametrically opposed, but we could always talk on the same plane and avoid total derision. Not a day goes by that I don’t wish I could call him up and explain some dense kernel of information I’m parsing apart. He grew up in the twilight of Apartheid in South Africa, and our family were originally Jewish refugees fleeing Russia, so he had this incredibly tangible relationship to civil rights in America, which remains acutely extant. As for my mother, I bet she could explain the waves of Ku Klux Klan membership and has a bearing on the colonial eras of Florida. I know she looks off the interstate overpasses towards Micanopy with a bit more curiosity now. How’s that for a soppy saccharine answer?

Historical Society, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

Billboard near Interlachen, Florida, 2016

You say that you aim to address critical questions facing our country. Do you think that a fine art documentary approach to this subject is the most successful way to reach a large audience? What other methods are you using to reach the public at large with the information you are discovering?

Well I understand both the naïve assumption of critical agency within the art sphere and the solipsistic counter, but I feel like those boundaries and edges are important in so much as they ultimately determine what a medium or form is capable of. That’s why I want to work towards publishing my first book, an anthology of sorts. And moreover, that’s why I want to write in addition to showing and making work. Whether it’s Harper’s or a lower tier gallery, they have their place, their audience, and of course their own limits. I believe that the more we can vary what constitutes art and break down the insider ethos of art, the more relevant art will be. Understanding that the timeline involved with an exhibition could never match digital journalism is important. For me, I want to ask how do we make contemporary art more relevant? More urgent? More applicable to fields such as activism or investigative journalism?

Hitchcock’s Grocery, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

Trail Camera, Little Orange Creek Nature Preserve, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

Michael, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

I will admit though, I am dreadfully pessimistic, and I try so so hard to ignore a great deal of artistic “discourse” as it just drives me mad. I want art to be about culture, to operate in the world. I just finished a longf orm piece about the restoration of the Florida Everglades and the immensely delicate political dance taking place, and I feel like that was a more apt, more effective means to engage than just making photographs. I was able to have U.S. Sugar, the largest producer of sugar cane in the United States, reply to my piece publicly. That is a public dialogue right? But I also know that my photographs would do things that the article could not. It’s really rewarding for me to see the response something like that gets and to be able to track a piece through data analytics. You’d be hard pressed to do that with a print. Regardless with all this in mind, I just want to tell stories, and more importantly I want to become better and better at telling stories, to be able to take some dense, impenetrable thing and weave it into a story anybody can understand or find meaning in ultimately.

When we first spoke, we discussed the natural progression of this work turning into a book. Can you tell us how you ideally see this work being published and when?

Well, that’s my big goal for the year. I’m planning to spend a few weeks working on the idea in November when I go to a residency at the Hermitage Artist Retreat in Florida. I see Cracker Politics as a book with long form essays, stories, reported pieces, and plates of photography, among other things. I’m really interested in making podcasts along with the book. I guess my big question is to self publish or pitch the book.

The when is what keeps me up at night. But I was hoping you might tell me?

Portraits for Sale, Stagecoach Shop, Micanopy, Florida, 2016

Near the Railroad Tracks that Divide Town, Hawthorne, Florida, 2016

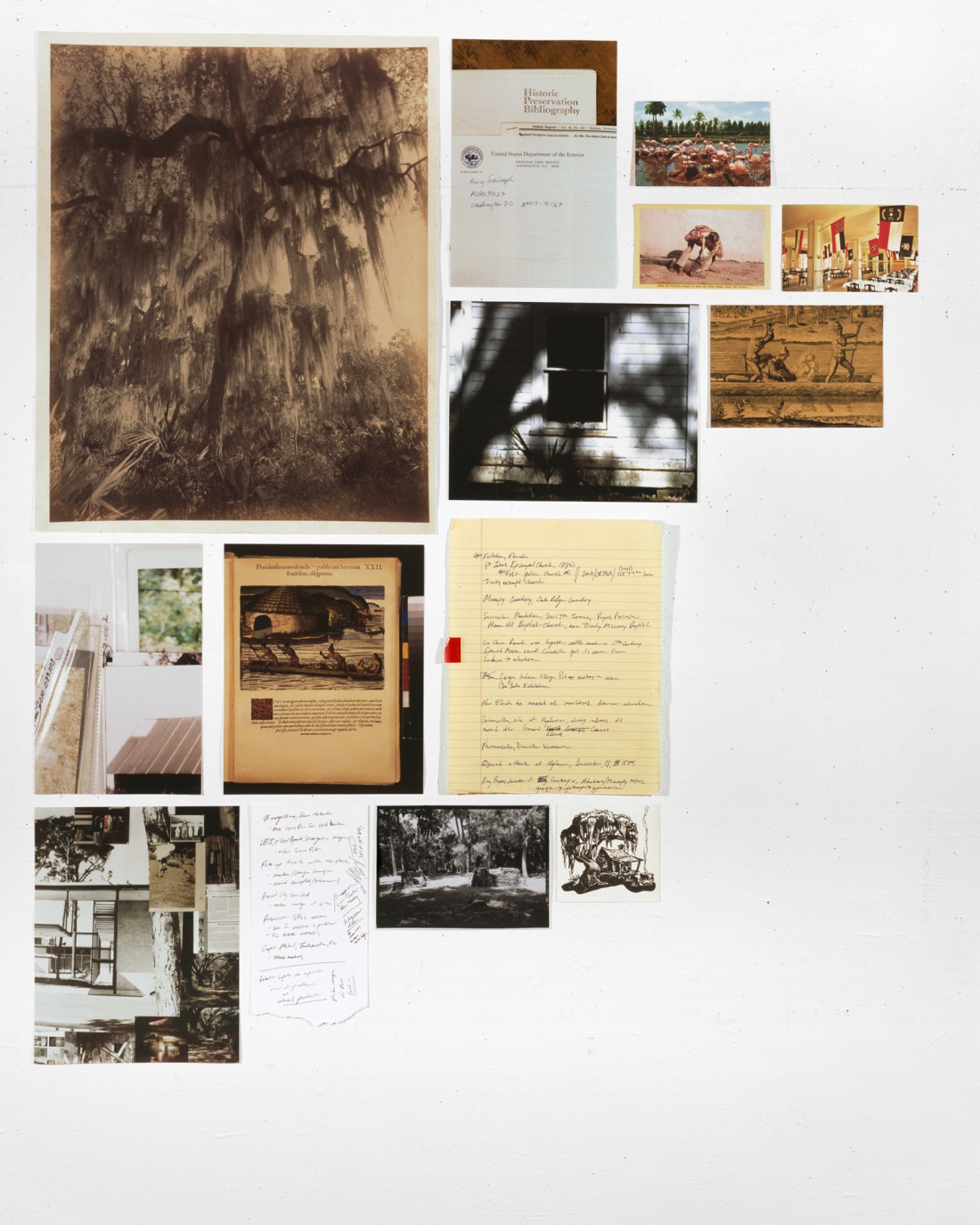

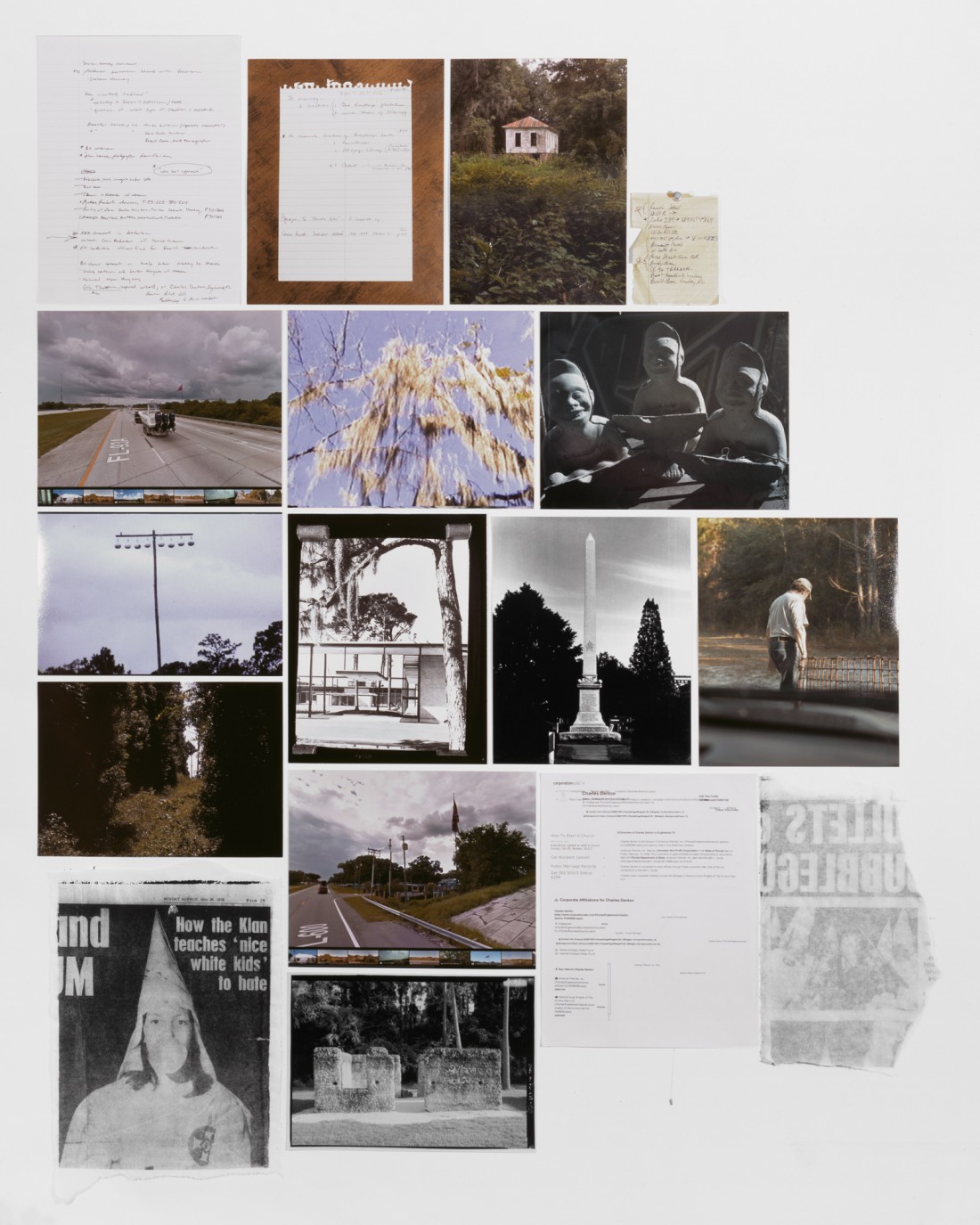

Atlas 1, Shadow Cultures, 2015

Atlas 2, Salus Populi, Lex Suprema, 2015

Atlas 3, Memory Suits Desire as if Free from History, 2015

Atlas 4, Phantom Documents, Invisible Monuments

Check out Michael’s recent essay on the Sugar Industry here, and their response here.

To view more of Michael’s work, visit his website.