Millee Tibbs’ work derives from her interest in photography’s ubiquity and the tension between its truth-value and inherent manipulation of reality. Tibbs is an associate professor of photography atWayne State University in Michigan. She holds an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. She is the recipient of two MacDowell Colony fellowships, as well as multiple national and international artist residencies awards. Her work has been published and exhibited internationally, including at the Pingyao International Photography Festival, China, and at the George Eastman Museum, NY.

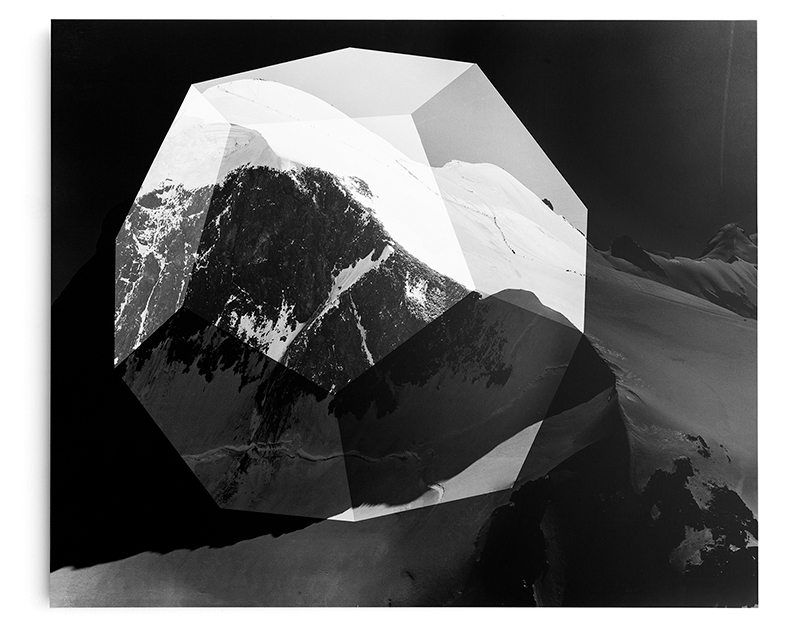

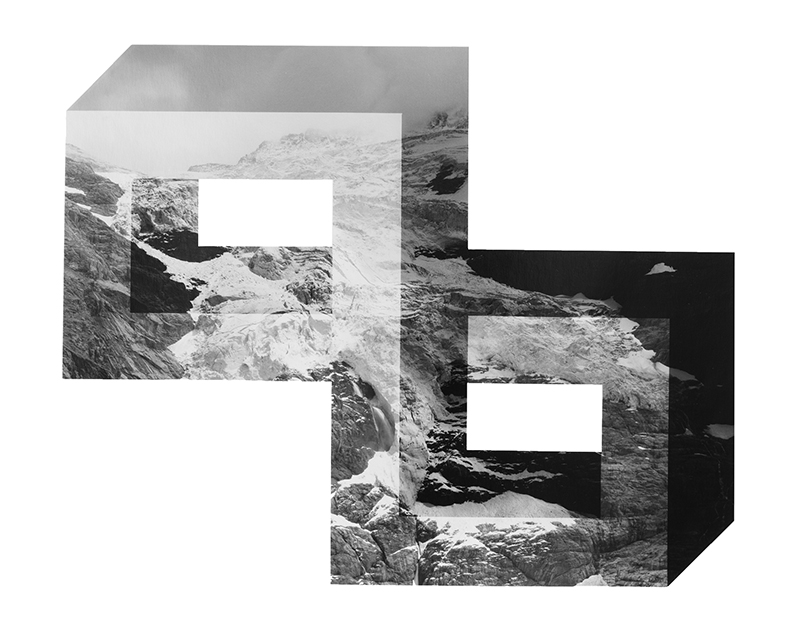

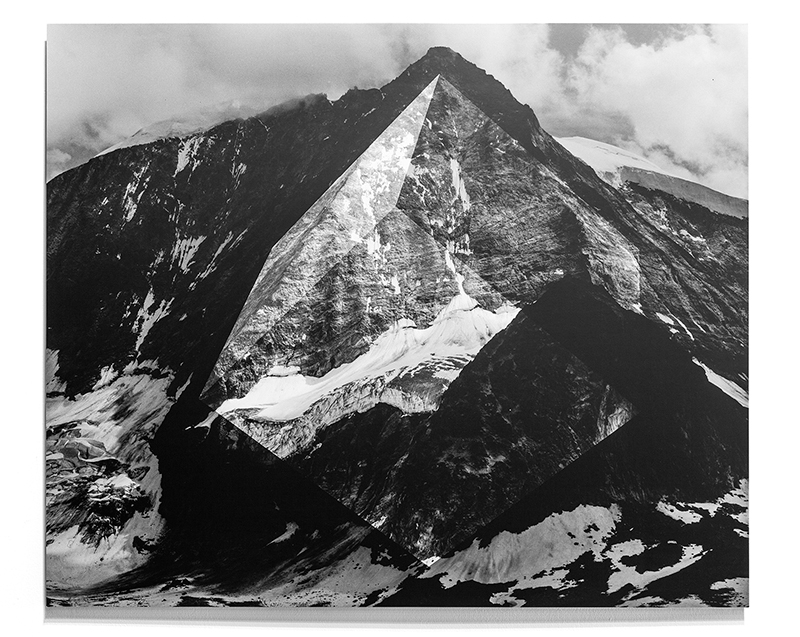

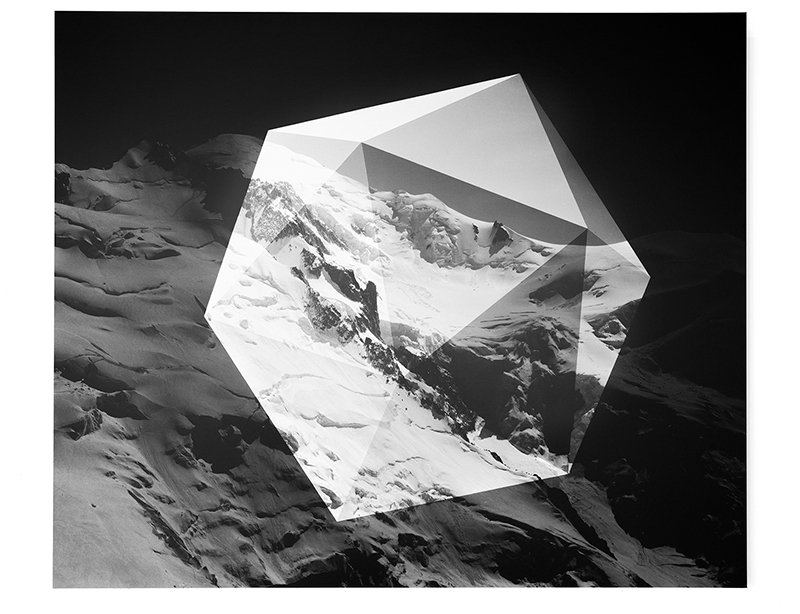

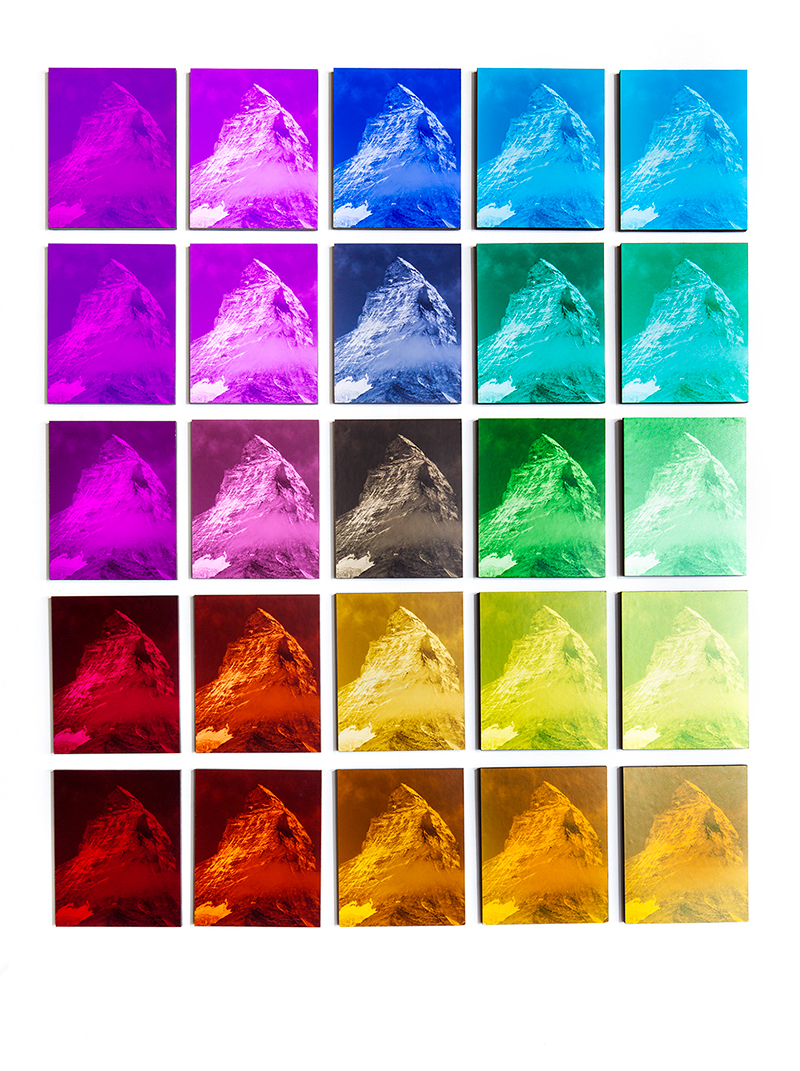

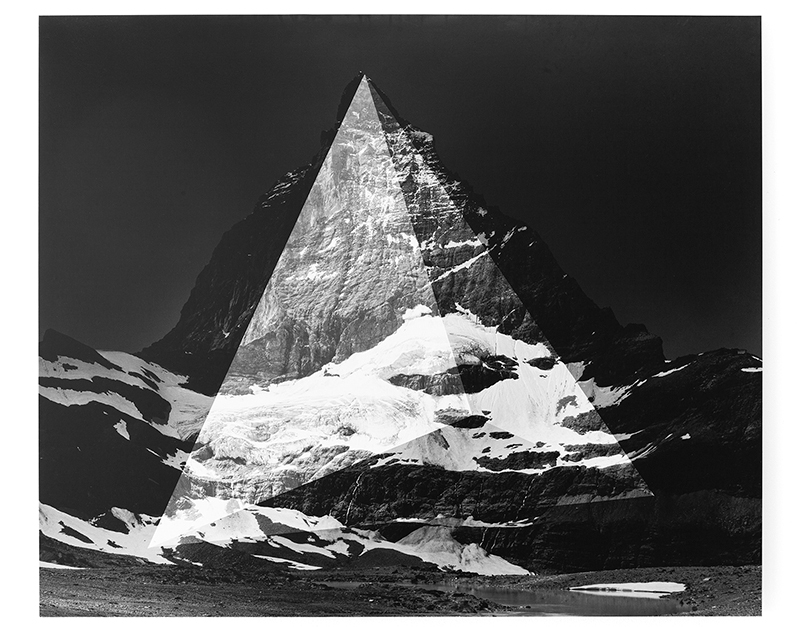

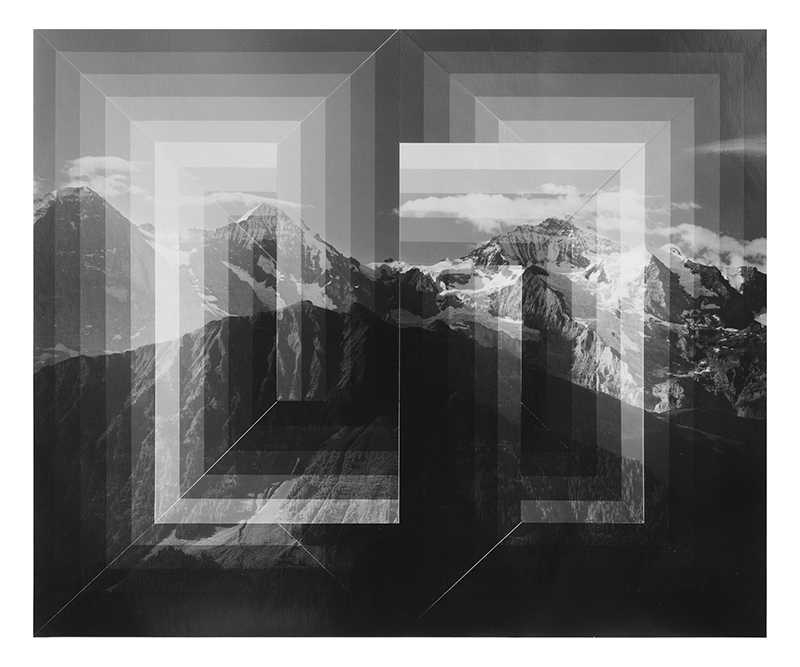

Mount Analogue

Using photographic images of mountains as a surrogate for the sublime experience, Mount Analogue explores the paradoxical relationship between photography, which can only represent what is in front of the camera’s lens, and the ineffable nature of the sublime experience that, by definition, exceeds the limits of perception. Using darkroom sleight of hand in tandem with perceptual abstraction, I explore the assertion of the logical mind’s attempt to rationalize and tame the incomprehensible. Just as the mountain symbolically bridges heaven and earth, my images attempt to transcend the objective limitations of the photographic to approximate the sublime experience.

Kyra Schmidt: Millee, I have to say I am a big fan of your scholarship. I began this interview wondering to myself if there are questions you might have not yet been asked before.. then chuckled. It seems like a fitting start to discussion on landscape photography.

You are traversing new territory with your most recent series Mount Analogue. Akin to digital manipulation but in the darkroom. Photography always seems to come back around, turning in on itself again and again. What made you aspire to explore the darkroom once more?

Millee Tibbs: Thank you, Kyra! I am a fan of your work, too.

There are a few different reasons I turned to analog for this project. In general, I am interested in where “truth” and “fiction” coexist, which is why I am drawn to photography in the first place. In many of my recent works, I bring together contrary visual systems to generate tension between truth value and manipulation.

For Mount Analogue, I wanted to explore the contradiction between the Sublime, an ineffable experience beyond imitation, and the photographic, an image which can only represent what is in front of the camera’s lens. I love the poetry of the indexical tie between photograph and subject ⎼ this string of light that traverses time and space to bind a photo to its referent. So much of the truth value of photography is bound up in that. I am also fascinated by the alchemical properties of the analog photographic process ⎼ the quest for immortality through the transformation of metals ⎼ and how this relates to the mountain as a site of physical and mystic transformation. So… it seemed like the best way to achieve sublime photographic transformation, while undermining truth value, would be in the darkroom.

On a more personal level, I love being in the darkroom. It’s a magical place that is much more satisfying to me that the digital realm, although working digitally revealed the possibilities of analog manipulation to me.

KS: With Mount Analogue, your making visible the filtering and sleight-of-hand that landscape pioneers such as Ansel or Weston fought so hard to hide. The things that you were never supposed to see in a photograph. How did this aesthetic decision manifest?

MT: One of my gripes with photography is its inferred transparency ⎼ as if the photograph represents some unmediated truth. Adams and Weston presented us with unmarred and “virgin” vistas of the American West. What’s left out of those images are the roads that got them there, the people who displaced the land’s original inhabitants, and the tourist industry that exploits an extremely patriotic version of American history. That exclusion is an act of mediation. I don’t want to disguise mediation, I want to emphasize it. So many decisions are a part of the creation of any photograph ⎼ I want to draw attention to those decisions and use the tools of photography to highlight the abundance of choices that are available to every photographer and are a part of every photograph.

KS: In our contemporaneous moment there are many photographers interested in the ineffable nature of experience or photography’s ubiquity, adopting a hand-altered approach to image-making ⎼ their aesthetic often organic or chaotic. I’m thinking of artists such as Letha Wilson, Meghann Riepenhoff, Aim Deuelle Luski, to name a few. With your exploration of similar issues, I’m interested, where does the geometry that we see recurring within your work gain its footing? How does it tie in to your process and ideation?

KS: In our contemporaneous moment there are many photographers interested in the ineffable nature of experience or photography’s ubiquity, adopting a hand-altered approach to image-making ⎼ their aesthetic often organic or chaotic. I’m thinking of artists such as Letha Wilson, Meghann Riepenhoff, Aim Deuelle Luski, to name a few. With your exploration of similar issues, I’m interested, where does the geometry that we see recurring within your work gain its footing? How does it tie in to your process and ideation?

MT: Like a lot of contemporary photographers, I am interested in interrupting the image and drawing attention to its artifice. My artistic development was strongly influenced by Post-modern artists and theorists. I love contemporary work that combines self-reference and materiality into a new aesthetic language.

The geometry in Mount Analogue is borrowed from 1960’s and 70’s Op Art. For me, these perceptual abstractions most closely embody a sublime experience – an image that is indeterminate and in a constant state of becoming. They playfully reveal the limits of perception. Like them I want to draw attention to the mechanics of vision, specifically photographic vision, and combine two optical illusions (landscape and geometry) to see how they affect one another.

KS: Your reference to Op Art as an influence for Mount Analogue is an important connection for me ⎼ one I hadn’t yet considered. You’ve expanded the geometry to the frame as well, toward a non-traditional presentation of imagery. Why?

MT: The rectangle can feel a little oppressive, no? It’s a remnant of Western art historical painting. Shouldn’t photographs really be circular? Eastman thought so, even though that never caught on…

Anyway, with a selection of works from Mount Analogue, I wanted to echo the internal geometries in the frame while still referring to conventional framing techniques. I kept the mat and the black frame, but shaped them to emphasize the sleight of hand you referred to earlier, instead of presenting the landscape as though through a window.

KS: I appreciate how your unconventional framing and darkroom processes foreground the materiality of each image. Artist and theorist Barbara Bolt would suggest that by attempting to order the world, whether that world be material or subject, we close ourselves off from it. For me your work does just this. The gleaming, sublime mountaintops become secondhand to contrast filtering, geometry, and framing ⎼ I almost don’t see a mountain anymore. Is this your intention?

MT: Yes, I think so… although I wasn’t thinking about it specifically in those terms. This question might link back to ideas of ubiquity. I’m curious what you would see in these images without the geometry. It takes an incredibly intimate experience with a mountain to be able to distinguish it from other mountains. They all kind of look the same, at least they share very similar properties. The mountains I am photographing are incredibly iconic ones (the Matterhorn, the Jungfrau Range, Mount Blanc…) so maybe they are a little bit more recognizable. They have also been imaged many (!) times. My unaltered photographs are no different than any that preceded them. Would those images bring you closer to the experience of the mountain, or would they instead present you with a simulacrum that points to the recirculation of these images? Would you see the mountain that straddles the Swiss and Italian border, the mountain first summited by Edward Whymper that killed four of his climbing party on descent, or the Toblerone logo? Sometimes what we see has very little to do with what is present, but rather with what we know. I am dubious that photography in any form can bring us closer to an experience. Maybe I am trying to see how far I can stretch the photograph from the referent before it snaps?

KS: Looking at both your images and your installation, you are exploring the possibilities of exhibition making as something to be encountered. You’re putting forth a different model of how things might be ⎼ art getting released into the world as an event, not a personal experience.

KS: It’s funny, as you stated earlier, the photographic is often tied to truth value via its index. And yet, traditional photographic representation seems to offer us (or maybe just me?) a frozen slice of life furthest from real, lived experience. The sensation of being-in-the-world ⎼ feeling warmth from the spotted sun on your skin or experiencing the aura of grandeur mountain tops ⎼ lost to the thing-ness of the photograph. Ansel might have been close to capturing such phenomena in his heavily altered silver gelatin prints, as is Meghann Riepenhoff in her raw and rooted cyanotypes, and you in these reverberating illusions of landscape. There is something more truthful here for me.

As we go deeper into the re-use of images and the further abstraction of the medium, what do you think this says about the state of contemporary photography? What, for you, is the function of photography once it has been shorn of its claims to verity?

MT: Those are good questions and ones I am curious about, too. I suspect that many contemporary artists who are drawn to photography, like myself, explore abstraction because it is the thing that the medium does least well and therefore presents an interesting challenge. How can I take something that is familiar and ubiquitous and make it unfamiliar and unsettling? I also think that as digital technologies dominate our daily lives there is a longing for analog tactility.

I’m not sure that photography can ever be completely severed from the real, which is why it is so much fun to try.

KS: In this period, a critical mass of artists have embraced an expanded definition of photography that is open and fluid to move across media, process, or history. As an educator, do you feel that photography in academia should be reshaped in light of contemporary practices?

MT: Yes and no. While most contemporary artists embrace a pluralistic practice, I still believe that we approach art-making through the lens of media, which determines how we respond to the world around us. The things that concern photographers are very different than those that concern sculptors, for example. First and foremost, photography contends with light. Sculpture has the challenge of gravity. Both mediums deal with space, but in very different and, arguably, oppositional ways. Yet, some incredibly interesting work results from sculptors who engage photography: Letha Wilson turns photographs into sculptures, while Thomas Demand builds sculptures to be photographed. Both began their careers as sculptors even though they are lauded in the contemporary photographic canon.

So, regarding academia, I think that undergraduate students should have a strong medium-specific foundation (which is an increasingly unpopular viewpoint) that addresses craft and concept in equal measure, but I don’t think that this should be restrictive or constricting. Graduate students, on the other hand, should really be pushing against the boundaries of convention, which might mean abandoning photography entirely. What I don’t think is useful is a fetishization of process or form that eclipses content.

KS: I have a very similar opinion to yours in this respect. I feel that the artist as creative and critical thinker is important now, in our cultural and political climates, more than ever. One of the aspects that draws me to your work is the scholarship behind it. As an artist interested in such discourse, I am interested, how did you come to navigate this space? The intersection of being the artist, the critic, the writer/researcher, the theorist, etc.

KS: I have a very similar opinion to yours in this respect. I feel that the artist as creative and critical thinker is important now, in our cultural and political climates, more than ever. One of the aspects that draws me to your work is the scholarship behind it. As an artist interested in such discourse, I am interested, how did you come to navigate this space? The intersection of being the artist, the critic, the writer/researcher, the theorist, etc.

MT: Some of these roles came naturally, others are a result of choosing a career path in academia. Thinking about and responding to how we make meaning through images has been at the crux of my practice since the beginning, as has reading photographic theories, so it’s no surprise that these have found a home in my work. Research and writing fold a little more neatly into my role as an educator, but also create a symbiosis with my art work. I am continually surprised how much teaching influences my creative practice. I enjoy that my work can serve as a platform to discuss questions of photography, or that my artistic research can lead me to curatorial and writing projects.

KS: Millee, it has been such a pleasure speaking with you. To leave us off: What are you working on this summer? ⎼ What is in store for you this year?

MT: Thank you, Kyra! Your questions have been so thoughtful! I’ve really enjoying thinking about them. As for the eminent future… I am working with some photographs that I made on a trip to the Himalaya last summer. It’s another phase of Mount Analogue. Aside from that, it’s home renovation and hopefully some camping!

To view more of Millee Tibbs’ work please visit her website.