From Outside Looking In to Inside Looking Out by Stephanie Bailey

Enri Canaj is a photographer who has been very busy lately, given he is based in Greece. A country buckling under the pressure of almost five years of straight recession coupled by a social crisis that has been worsened by an EU treaty ratified in 2003 that essentially forced Greece into becoming the main processor of all illegal immigration into the European Union despite its lack of resources to do so. Canaj has been an eyewitness of this complex cocktail that has rendered Greece a country that speaks not just of history, but of a world in crisis.

In 2010, statistics stated that some 90% of all illegal border crossings into the EU take place in Greek territory, with immigrants coming mostly from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, a reflection of the geopolitical conflicts currently ravaging each region, and the influx continues. These people are common a sight in Athens, as western tourists take part in the cultural tourism that keeps this city alive; peddling cheap products made in China – a crude image of capitalism eating its own tail. And yet, despite the ease with which this situation might be covered in bursts by the mainstream press, Canaj’s work has consistently surrounded themes of migration within the Balkans, and more specifically the experience of immigrants in Greece, suggesting a dedication to a cause, rather than a newsworthy story.

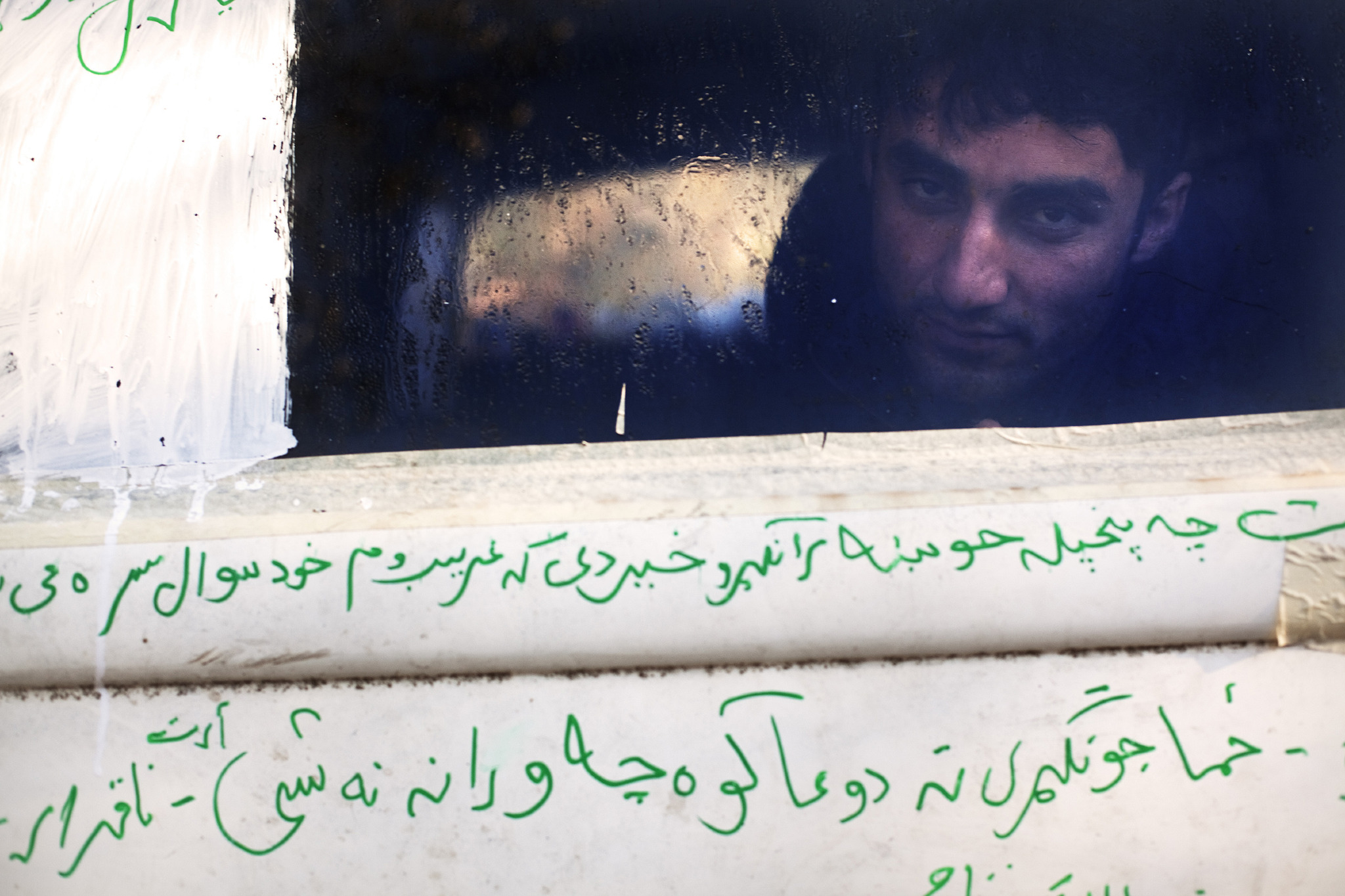

Since 2007, when he took part a yearlong project on migration with Magnum photographer Nikos Economopoulos entitled the City Streets Project organized by the British Council, this focus has become one of the key aspects to his work. And despite his professional status as a photojournalist, Canaj’s images reveal a more personal relationship to the situation of the migrant on the ground, given that Canaj himself was an immigrant who came to Greece from his native Albania in 1991 at the age of eleven. Having experienced first hand what it’s like to exist on the outside looking in, Canaj translates what he sees, and sends it back out into the world so as to reflect a sense of humanity in the lives of those so often treated as less than.

Can you talk about how you developed this focus on immigration?

The issue of immigration has always bothered me. It has been in my mind from the moment I started photographing in 2006, there was a massive wave of immigrants coming into Greece from Asia and Africa. It was interesting because this brought different cultures into Greece that were, back then, unfamiliar. This has become an important theme in my work because I try to show how the situation has changed from when I began to now, that is to say, much worse, and in Greece, these people come from countries that are very far from the philosophy of Europe. In the past decade, Athens has changed rapidly and it has been interesting, even necessary, to record this and explore how these two realities interact – the difficulties of the immigrant entering into a society that is clearly experiencing its own difficulties. I think about how people have walked here on foot, taking risks to find a better life, and then finding themselves trapped in a situation they did not expect to find themselves in.

It is around this trend of immigration that the project with Nikos Economopoulos emerged after ten months of discussions and workshops and looking at immigration in Athens. What also played a role was a curiosity I had to meet these people. The immigrants who have been coming to Greece in the last decade or so don’t want to stay here, but in these small spaces where they reside, they try to bring something from their past; a photo of their parents, something that reminds them of the places they have left behind. In Greece, the people who they live shoulder to shoulder with become their family as large numbers of people are usually living together in one space.

You have said that your experience of moving to Greece from Albania in 1991 has given you a closer perspective to the life of the migrant. How has this affected the way you capture your subjects, and how you interact with them?

As an immigrant from Albania I lived for many years on the margins of society as someone who existed illegitimately in this country. I was eleven years old back then, and Greece did not keep records of its immigrants as it does now because it did not have experience of this kind of immigration. It was as if you were not in the country yet, even though you were physically present.

Even now after so long, sometimes it still feels as if you don’t belong anywhere: An immigrant who goes to a new country has a sort of rebirth in that they have to start from zero, often with nothing. Knowing that I’m an immigrant, too, I develop a friendship with those I photograph in that I am also considered one of them. This gives me a certain freedom as a photographer to enter into situations and move amongst the people I try to represent.

Your images portray a very difficult existence that is not always shown or dwelled upon in mainstream media. What is it like to work with people who have been directly affected not only by the EU’s immigration policies — the 2003 Dublin II Treaty, for example — but also by geopolitical events in Africa and Asia that have driven so many people to seek refuge in Europe via Greece?

A lot of the time I try not to show the actual conditions, which are much worse than as they are portrayed because I also have a need to show these people as proud and beautiful, despite the tragedy and the hardship. The conditions are such that I want to bring my own eyes to transform what I see; it’s something like going against ugliness, which is always very easy to record in these areas and spaces where immigrants live. These people have gone through a lot and it is not always easy for you to believe that they have risked their lives to get here. It always affects me. For example, a majority of those from Afghanistan are minors and at first, I could not understand how a child of fourteen years of age could travel alone, across lands, in very dangerous circumstances, all the way to Greece.

Everyone has a story to tell, especially those who have been forced to migrate, and everyone has a reason for leaving their home. Arriving in Greece, however, they soon realize this is not the Europe they imagined. The reality for them is much worse than fiction.

How have you seen Greece change through your focus on immigration?

Greece has changed a lot. In the beginning, it changed for the better, until and shortly after the Olympic Games in 2004, and then things started to change. The immigrants were one of the first sections of society hit by the crisis and remain one of the hardest affected: vulnerable and trapped because it is not easy to leave the country, so they are somewhat locked into a very difficult situation. On the other hand, they have also paid a lot of money to come to Greece, and have to find a way to return, which is also tough. Now things are even more difficult and there are no detention centers or places for people to learn the Greek language and become part in society.

In Greece as there is no work, they do not get medical help and are often left looking for food in the garbage. They are trapped by the fact that they cannot get their asylum application processed, caught in some kind of limbo, or they simply don’t have the money to continue their journey. And even though the European Union has since provided funding for people to return to their countries, this doesn’t fix the situation – everyday more people come to take their place and the cycle begins again. Since 2011, I have noticed that more people have been coming into the country in comparison to the years before that.

You have said you want to give immigrants dignity through your images. How is this important for you?

In working with these themes of migration, I try to keep a distance in order to see things more clearly. I try to show a different face, not of the hungry and suffering immigrant, though this is often the case, but instead to show dignity and hope. I want to show something different to what people have heard in the press, or to show a side to the situation that they were not aware of. I want to add with my subjective eye in these difficult circumstances, to beautify in my mind what I see, and to give that beautification to these people: to show them in a different light as they hold on to their dignity so as to have the strength to move forward in life.

If there is a universal quality to your work, which is rooted in very specific localities, what do you think such qualities are?

I think it is respect for people and between people, and the hidden beauty that everyone has inside of them, which can so often act as the light of optimism that makes a bad situation more bearable, more dignified, more human.

For more work by Enri Canaj, visit his website

Stephanie Bailey is an art writer based in London and Athens, where she has covered contemporary art extensively both as Art and Culture Editor for Insider Publications, regular art contributor for Odyssey, as well as contributor to Aesthetica, Art Papers, Art Forum online, LEAP and Yishu Journal for Contemporary Chinese Art.