Noah Rabinowitz is an American photographer, writer and filmmaker based between NYC and Paris. His photographic clients have included The New York Times Magazine, Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, Rolling Stone, The FADER, Bloomberg Businessweek, Harpers BAZAAR, The Wall Street Journal, Virginia Quarterly Review and The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard. Aside from independent projects, and frequent editorial and commercial commissions, Noah is also an editor with OSMOS, an editorial and curatorial platform focusing on contemporary art and photography, and a contributing editor with Guernica Magazine, the award winning literary journal of art and politics. His writing has also appeared in VICE and The Wall Street Journal. Today we share his series Deep Space Control.

Deep Space Control

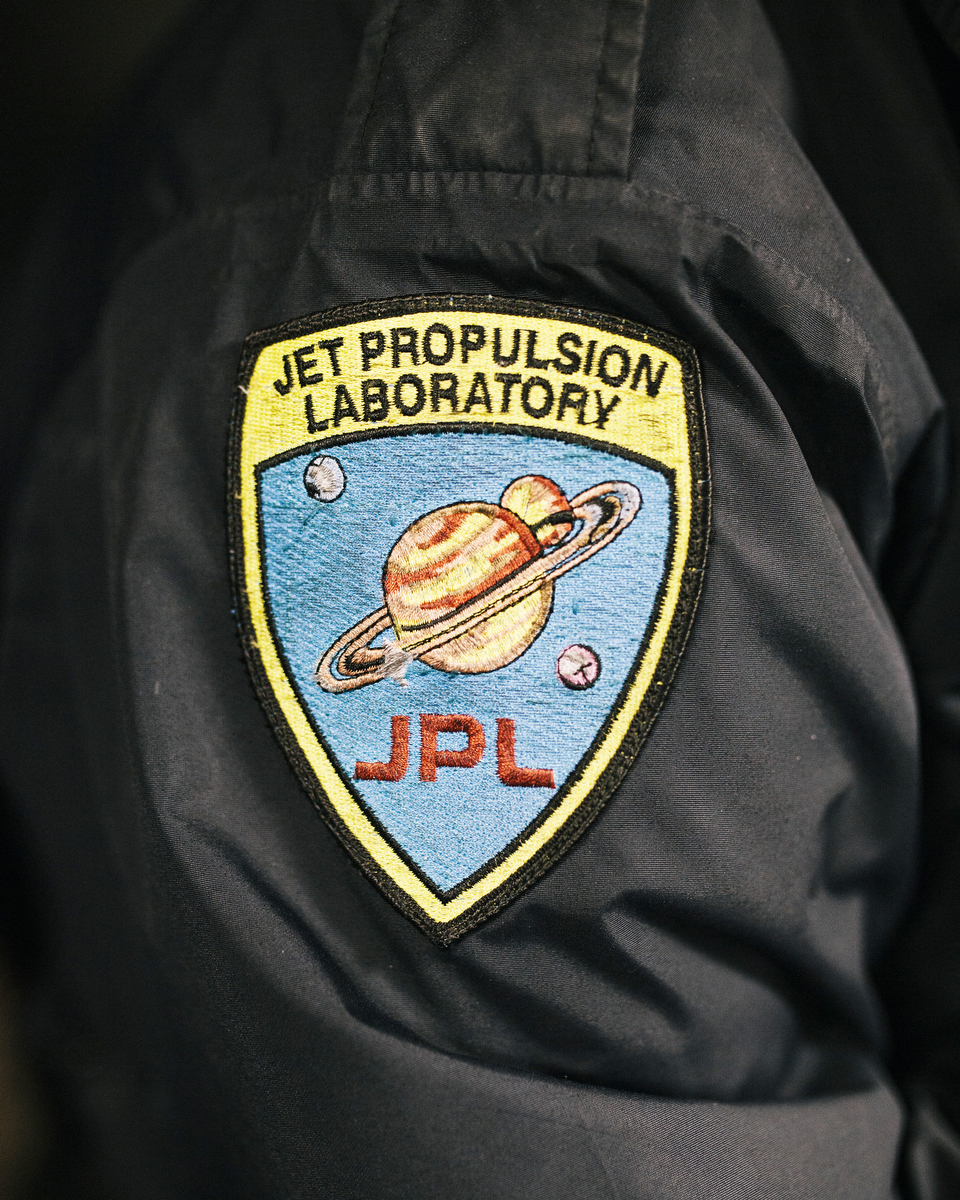

ALL IMAGES : JPL Labs, Pasadena, CA 2014

Two years ago, Voyager 1 became the first man-made object to enter interstellar space, a mind-boggling 18 billion kilometers from the sun. Its sister, Voyager 2, is not far behind, exploring the edge of our solar system in a mission that began 36 years ago.

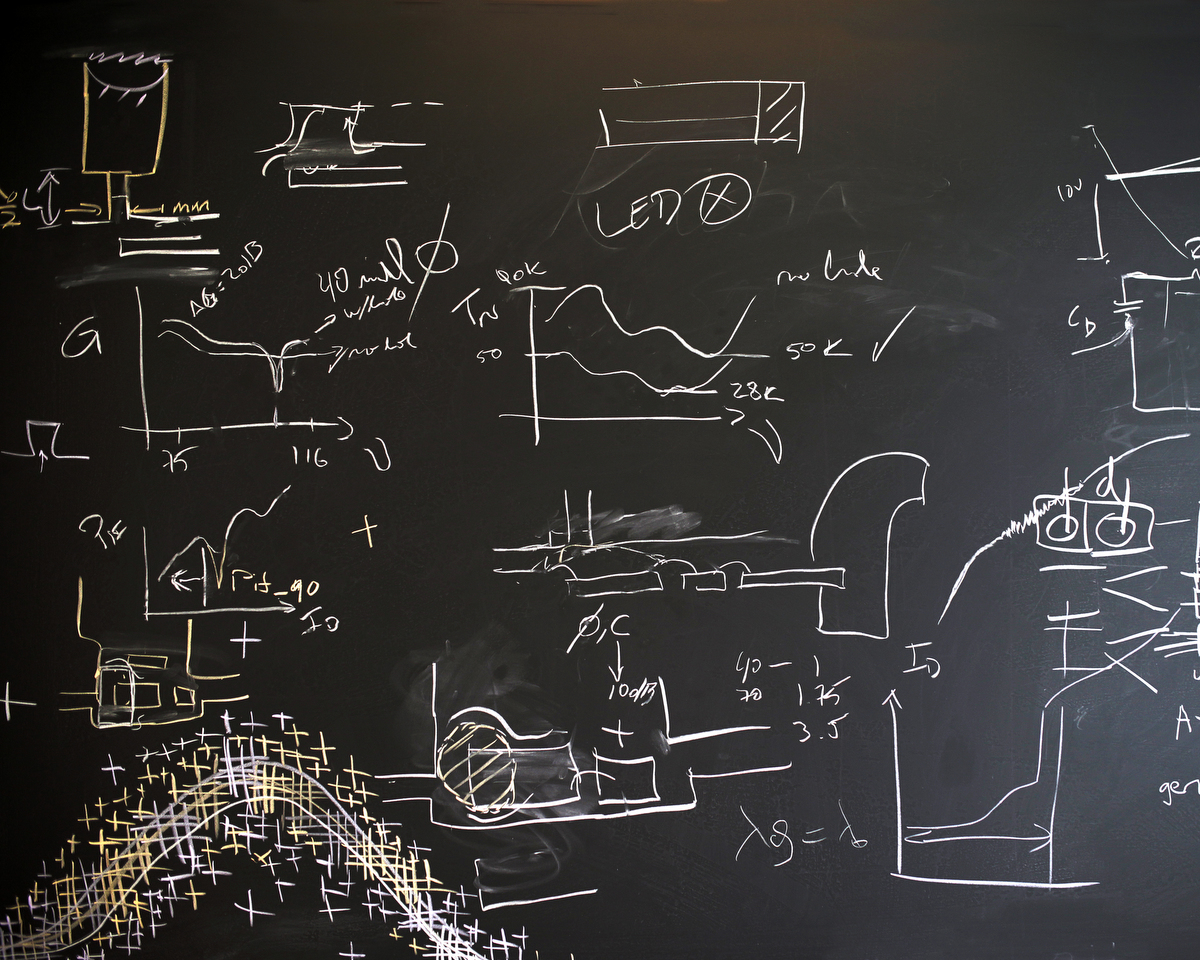

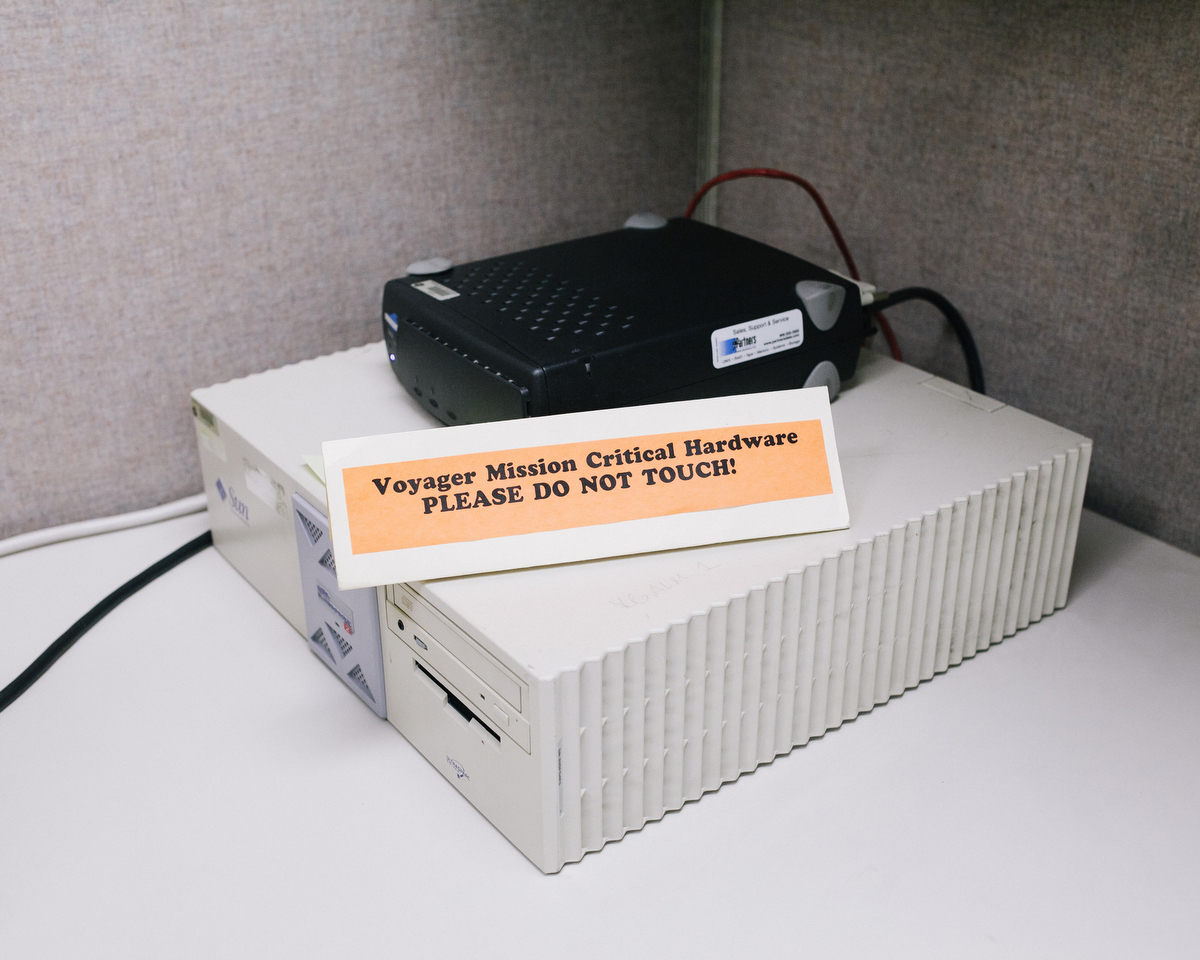

The probes, which have performed far beyond our best expectations, continue sending invaluable information to the most ordinary of places: An office between a dog training school and a McDonald’s on a nondescript street in LA. It looks more like something out of Office Space than mission control for a milestone in our space program.

“The mission control room is really just some screens, a couple rolling chairs and a fax machine,” says photographer Noah Rabinowitz, who was allowed to photograph there as well as the mission control replica at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

NASA launched Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 from Cape Canaveral, Florida, in 1977. They were designed to study Jupiter and Saturn, and each carries a Golden Record that contains images, sounds and greetings to any extraterrestrial civilizations. Voyager 1‘s primary mission ended in 1980 and its sister’s in 1989, but the little probes kept going. And going. And going. Voyager 1 passed Pluto in 1990, and NASA announced on September 12, 2012 that it had entered interstellar space. Despite the vast distance, the two probes continue transmitting information. That means there must be someone at home to receive it.

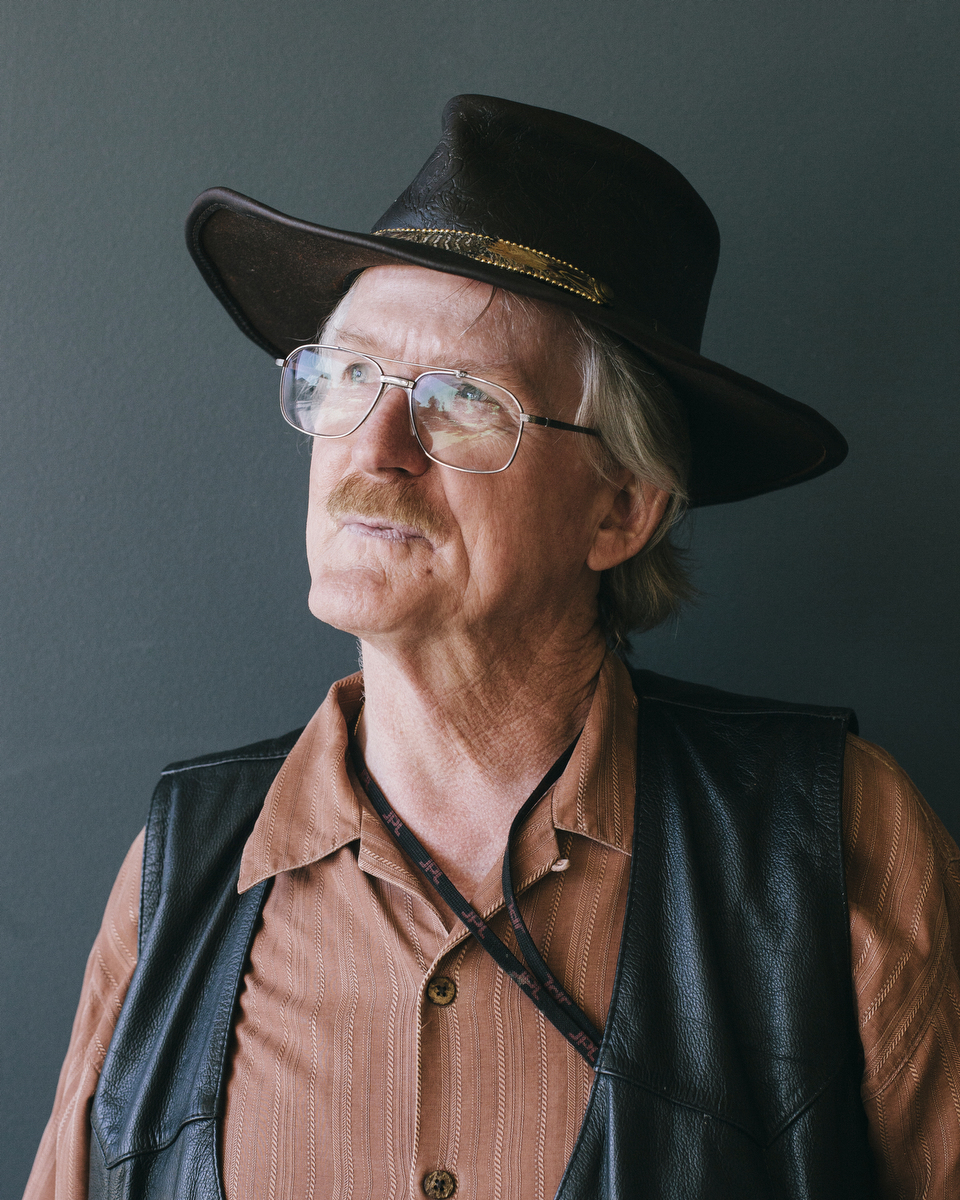

As fascinating as the probes, and the far corners of the solar system, may be, Rabinowitz’s most revealing photos capture the quiet quiet moments and wonderful personalities within mission control. Take, for example, Tom Weeks, a position controller who looks like he could be playing in a Guns N’ Roses cover band. He was part of the original launch, left NASA to attend film school, played in a few bands, had kids and came back.

“I tended to focus on the people because they are the kind of untold story of these space missions,” Rabinowitz says. “And in this case, everyone I met was pretty extraordinary.”

Programmer Larry Zottarelli is in his late 70s. He’s been with NASA for 55 years, and is so crucial—and dedicated—to the Voyager program that he hasn’t allowed himself to retire. He says he’d be happy to “simply fall over dead, right here.”

That may yet happen. According to NASA, the two probes have sufficient electricity and fuel to operate for another decade or so. Beyond that, NASA starts taking a much longer view, noting that in 40,000 years or so Voyager 1 will drift within 1.6 light-years or 9.3 trillion miles of AC+79 3888, a star in the constellation of Camelopardalis. And even that will not be the end. NASA says both probes “are destined—perhaps eternally—to wander the Milky Way.”

To view more of Noah’s work, please visit his website.