William Chan is a photographer and filmmaker. His work reflects upon the ramifications of U.S. foreign policies in the Middle East. He received his MFA from the School of Visual Arts. His first book, Ten Years After Iraq, was nominated for the ICP Infinity Award among other accolades and belongs to many collections including the Tate Modern, The Met, ICP, Harvard, and Yale library.

Ten Years After Iraq

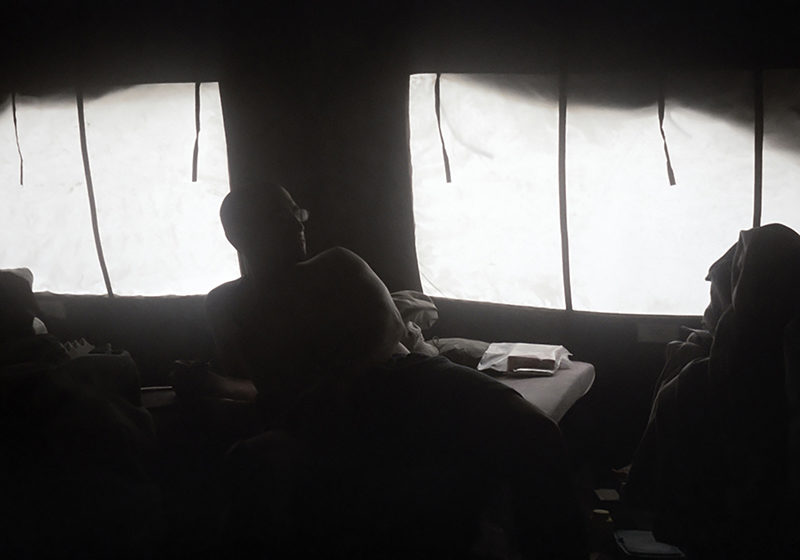

William Chan served in the U.S. Army during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Ten Years After Iraq is the journey of many veterans who have to reconcile the pride of one’s service with the outcome of the war in which they fought. It is a plea for individual release, and a hope for his country to reflect on its past decisions.

Could you first tell us a little about your army service. What made you decide to join the army?

I served 12 years in total, mainly in the Reserves component. I joined partly to serve my country, do something different, and maybe to seek an identity. I’m an Asian-American and immigrant. Growing up I was taunted a lot with racial slurs. Somewhere I am sure that played a part in me joining the Army. To validate my “Americanness.”

10 years after Iraq deals with your experience as a soldier, but mainly from the perspective of a veteran, years after you came back from the war. What triggered you to create this book? What is the experience looking back, 10 years later, at these memories?

I loved being a soldier and in combat. I wanted to be in war. Be part of history. In a very selfish way, soldiers train all their life for something that is catastrophic for everyone else. I drank the Kool-aid and romanticized being an American soldier and saving Iraq from its dictator.

I think we could have done something positive there if that was our focus but it wasn’t. Iraq was the classic “others” to us. As the Iraq war went on and Iraq became more of a mess I couldn’t repress my conscience. My country made a huge mistake and I was a part of it, both as a citizen and a participant. Making this book was my way of dealing with all of it, the pride, guilt, shame and so on. The pictures remind me of the brotherhood which I miss so much today. To go out on missions and to know the people you serve with would literally give their life for you if needed. On the other hand, the images of smiling kids remind me of the mess my country created for them. Where are they now? Are the kids alive today?

What made you, ten years ago, try and document Iraq using a disposable camera? What did you expect to capture? What did you think you would do with those images once you got back home?

I wasn’t a photographer back then. I wasn’t really documenting anything besides taking pictures for fun like a trip. Hence, in hindsight, I was totally guilty of treating Iraq as the “others.” I printed the pictures and stored in a box and didn’t think much of it.

The images in the book do not show ‘war’ in its typical sense or as we are used to seeing war in photography. Can you explain what stands behind these images. What story are you trying to tell us about this place, this time and this war?

The book is really about the psychological aftermath of war. Because of that, the images used are really quiet. Nothing overt or bloody. The book is equal parts text and images, and it plays off of each other. I wanted to convey the contradiction that exists in my head. The images are soft and unassuming but the text are charged. Stephen Mayes described better than I can, “this small book hits its target fast and hard, but so quietly that it’s hard to understand the quivering emotional vibration left in its wake.” The book is still very much from a first world perspective and I hope it makes us reflect on our view of ourselves in the global sense.

Photography is such a key player in depicting wars around the world, for years now. Photography as a “truth teller” and as a valid document of tragedies that accrue around the world – do you think that is still a valid pov on photography and war? How do you think war photography has changed over the years ?

Totally. As long as the viewer does the legwork and not get stuck in a vacuum. No one outlet will give you the complete picture but different outlets from different countries and platforms will definitely paint a better picture of war in 2018 than whatever was available in 1975. I think the economic shift from print to the internet has pushed many war photographers to use other means to tell their stories. A conflict story can now be told on facebook, twitter, instagram, periscope and such.

How did your fellow veterans, or army people in general have reacted to your book? Did some people have a problem with the books critical statement about the US role in the war?

Most of my Army friends haven’t reacted well with the book but they all have been respectful. No one cursed me out or anything. The truth is many people die as a result of the U.S. led invasion of Iraq. Some studies suggested 500,000 deaths on top of those displaced and wounded. It’s not easy to face your mistakes but what kind of people are we striving to be if we simply ignore this? It’s not just the soldiers or politicians that should be held accountable but all adult citizens too.

What do you hope people take from your book? Especially people who might not have a connection to the army or this specific war?

I hope people become more thoughtful about war. If the U.S. ever enters into another war, I hope we really think about it and be considerate of those who will be affected. What do we mean when we say “Make America Great Again?”

On a personal level, I hope people are more aware of the issues afflicting veterans. I had two friends that I served with pass away since last summer and that shook me. Their passing became the catalyst for me to seek help. I know that it could have been me. Soldiers are told to shoulder a lot but sometimes war and its memories are too much to digest.

You have started some great projects related to the book and your experiences in general, do you want to tell us more about them?

While the book was more emotional and cathartic, I felt it was meant as a precursor to real changes I can make in the world. I went back to Iraq in 2015 and met with an Iraqi photo agency. They employ local photographers to tell their own stories to the rest of the world. I really liked what they were trying to do. Eventually, I sponsored some projects they created and help bring their editor-in-chief to New York to meet with U.S. editors. I also help set up some panels for him to introduce his agency. Another thing I did was raise about $5,000 through the sale of the book for this great organization called RISC. They train journalists in combat life saving skills for free.

What was the best part of making the book? what was the worse part?

I am very proud of the book. It truly works as a book and not a collection of pages. The book was made during two crit classes while I was at SVA MFA Photo. A lot of credit goes to Charles Traub, Joe Maida, and my classmates. I don’t know if there was a worse part except I cried a lot in front of people. There were a few times I cried like 15 minutes straight. It was all those emotions I bottled up since Iraq.

Any advice for fellow artists who are thinking of making a self published book themselves?

1) Ask yourself why you are making it and what you want the book to do for you.

2) Make a book that’s memorable. Something you love and believe in.

3) Don’t over design it. Get a professional if you can’t design yourself.

To view more of William’s work please visit his website.