Bryan Schutmaat is a Texas-based photographer whose work has been widely exhibited and published in the United States and abroad. He has won numerous awards, including the Aperture Portfolio Prize and an Aaron Siskind Fellowship, among many others. His first monograph, Grays the Mountain Sends, was published by the Silas Finch Foundation in 2013 to international critical acclaim. His most recent publication, Good Goddamn, was released in 2017 by Trespasser Books. Bryan’s photos can be found in the collections at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Pier 24 Photography.

Good God Damn

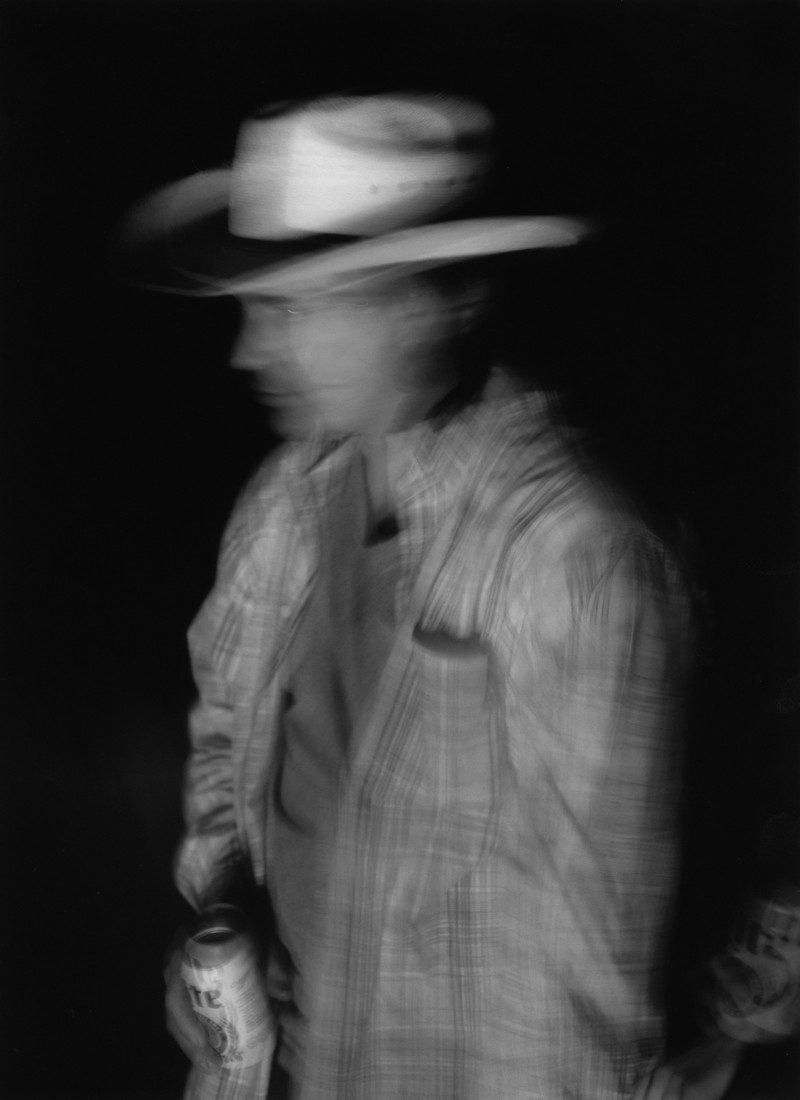

Good Goddamn is a short photo book about a man named Kris from rural Texas and his last few days of freedom before going to prison.

Porter: Could you start by telling us the story behind this book? Did you know it was going to be a book from the beginning?

Bryan: I didn’t think a lot about the project before I shot it, and I didn’t know it would be a book. It all sprang up pretty naturally. I first met Kris several years ago when my parents bought some land alongside Kris’s family’s farm in rural Texas. We got to know each other pretty quickly when I’d go to visit my folks. He’s a ranch hand and often came around to help out with things on the property. From the beginning, I was struck by his style and presence. He’s one of the few people I know who’s just totally real. With him, there’s no pretense and no concern for how others view him, so I was drawn to that, as well as his energy and mannerisms, etc. I used to tell him, “One of these days I’m going to take your picture,” but I didn’t get around to it until he told me that he would be going away to prison. It was my last chance to photograph him for while, given that he got a five-year sentence. At the outset, I just wanted to make a few portraits, but after looking at the photos from the first-day shooting, I recognized something in the work — a psychological atmosphere that I wanted to look into further. I’m not sure if this was real or imagined, but the weight of the impending incarceration and Kris’s emotional state became evident in the photos to me. In the following few days, we made photos each evening when he got done with work.

Porter: On one side, these photos are filled with somewhat juvenile antics – days fueled by mudding in trucks, drinking beer, smoking cigarettes, and shooting guns – and on the other side there is a mature emotion of two longtime friends having to come to terms with a harsh reality. I am curious how these photos worked as a way to cope?

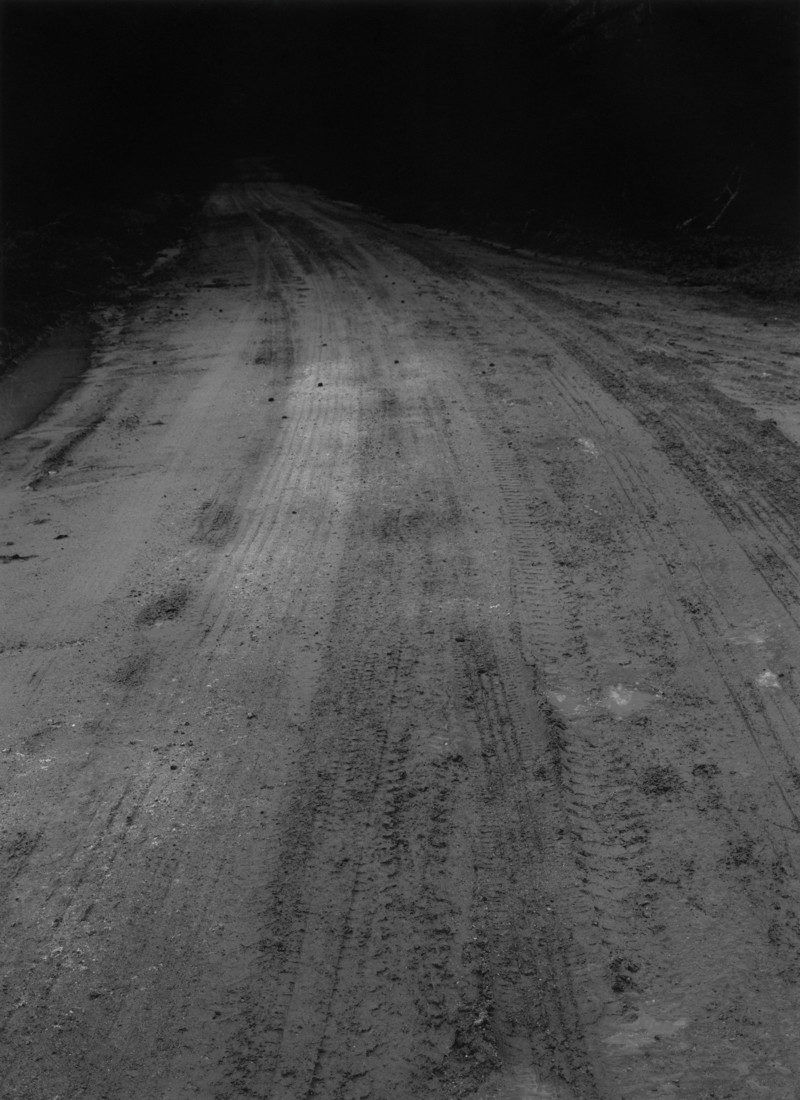

Bryan: In some ways Kris is a bit of a loner. Most of the time he’s secluded on his family’s land, which is down a dirt road, hidden by pines, seemingly far from friends and the outside world. Aside from his father and some occasional guests, Kris is usually on his own, finding solace in his relationship to the land, not people. But as neighbors, my family and I became close to him. I don’t know if the photo making process itself was a way to cope or if it was just our proximity and friendship that eased the pain somehow, and maybe photography could have been any activity that brought us together, like going fishing or grilling out or whatever. Many nights we stayed up late just drinking and talking about life and the difficulty of it all. Beyond the prison sentence, Kris has had it rough in all kinds of ways.

Porter: There is a great quote by Cartier-Bresson, that is “one eye of the photographer looks wide open through the viewfinder, the other, the closed, looks into his own soul.” Of course, all photographs are subjective to the photographer, but you seem to be doing more of the looking in to yourself than through the lens. What is the importance of this book for you? As much as I have enjoyed having this book, it’s not for me, is it?

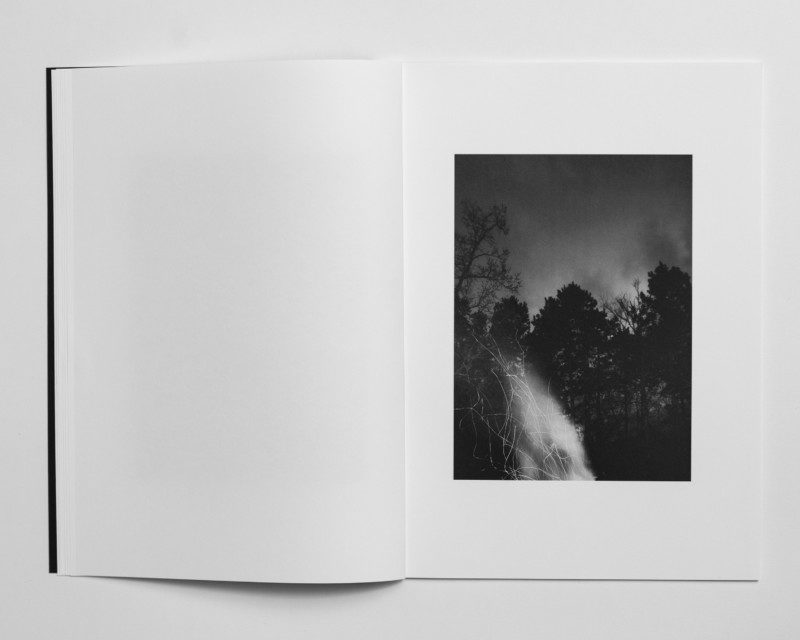

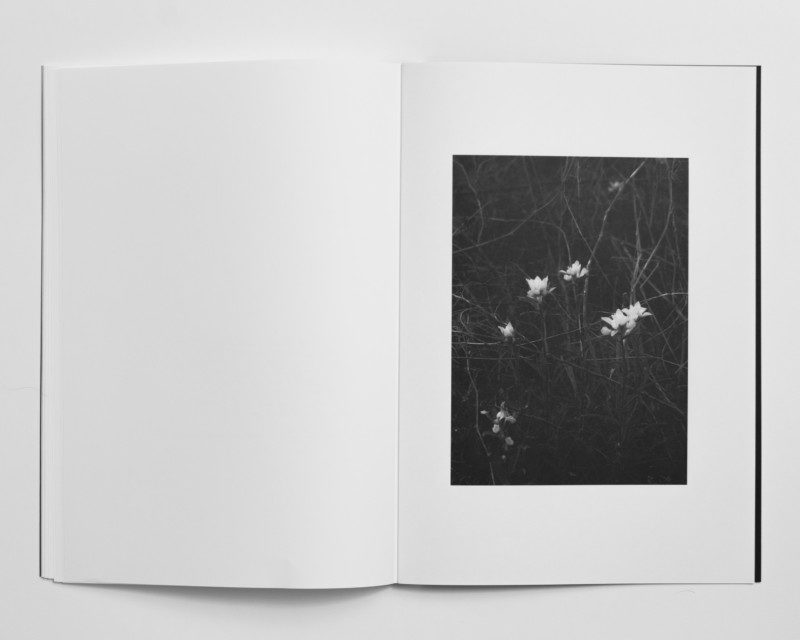

Bryan: Yeah, I think the book is mainly a record for Kris and me. With this work, I was definitely looking into a subject that was more personal and more emotionally charged than what might be called the “social documentary” work I had done prior. But even with a book like ‘Grays the Mountain Sends’, I think my entire approach to photography is to use the surfaces of people and places to express the inner life of some kind. The best photos are metaphors for something more than what’s depicted; often this is the turmoil inside the hearts of people, particularly the authors. Sometimes I try to work things out with photography in therapeutic ways, using it as a tool to contemplate issues and make my life better. Whatever the subject, it becomes personal and inward. And more generally, I think of myself as the most important audience member, striving to meet my own ideals and so on. I take the kind of pictures I want to see and be moved by. But I definitely want an audience. Inherent in photography is ease of distribution, and it’s beautiful that photos can be released out into the world for other people to see and contemplate. So this book is for you, too. Ultimately, it’s dedicated to Kris, so it’s for him as well. But honestly, photographers take more than they give, and I’m the one who gets the most out of this pursuit. I really think photography means the most to photographers.

Porter: You said in an interview once that you photograph “mountains, people and things” and while I can’t argue that those do not hold true in this book — more so against the peoples and things — there is a defining change in the photographic style in this work compared to the work you made for ‘Grays the Mountain Sends’. Can you speak a little bit about that this?

Bryan: This project was brief and cathartic, and the process wasn’t conducive to my usual, more meticulous aesthetic. I usually shoot large format, but this was shot mostly handheld so it’s looser, more gestural, and somewhat gritty. Still, I wanted it to have a certain sensitivity and a continuity with my other work, not through the style, which was a departure, but through a feeling toward my subject matter — a kind of brotherly sympathy.

Porter: What other books were you looking at that inspired you in terms of design, materials, printing process, etc.?

Bryan: Ray Meeks was a big influence on the project overall, but not so much in terms of design and materials. My collaborators, Cody Haltom and Matthew Genitempo, and I were thinking of something more akin to a zine than a proper book — like the punk rock paraphernalia of our youth. I lifted the idea for the binding from Andreas Laszlo Konrath’s ‘The Following is for Reference Only‘, which was done with small staples, but for ‘Good Goddamn’, we went with bigger carton staples and drilled holes to give it a unique feel. We also referenced John Gossage’s ‘Hey Fuckface’. Both books have swear words and handwritten titles on the front. Each ‘Hey Fuckface’ was actually written by hand. Cody wanted me to handwrite the title on every ‘Good Goddamn’ cover, but I didn’t want to do that a million times so we printed it offset.

To view more of Bryan Schutmaat’s work please visit his website.