Jon Feinstein is a Seattle and New York City-based curator, writer, photographer, co-founder of Humble Arts Foundation. Jon has curated numerous exhibitions over the past decade, including Future Isms at Glassbox Gallery in Seattle, WA; Radical Color at Newspace Center for Photography, in Portland, Oregon; Another NY for Art-Bridge at The Barclays Arena in Brooklyn, NY; and 31 Women in Art Photography at Hasted Kraetleur in NYC. His own photography and curatorial projects have been featured in Aperture, The New York Times, The New Republic, BBC, VICE, The New Yorker, Hyperallergic, Feature Shoot and American Photo, and his writing has appeared in TIME, Slate, GOOD, Daylight, and PDN.

Breathers

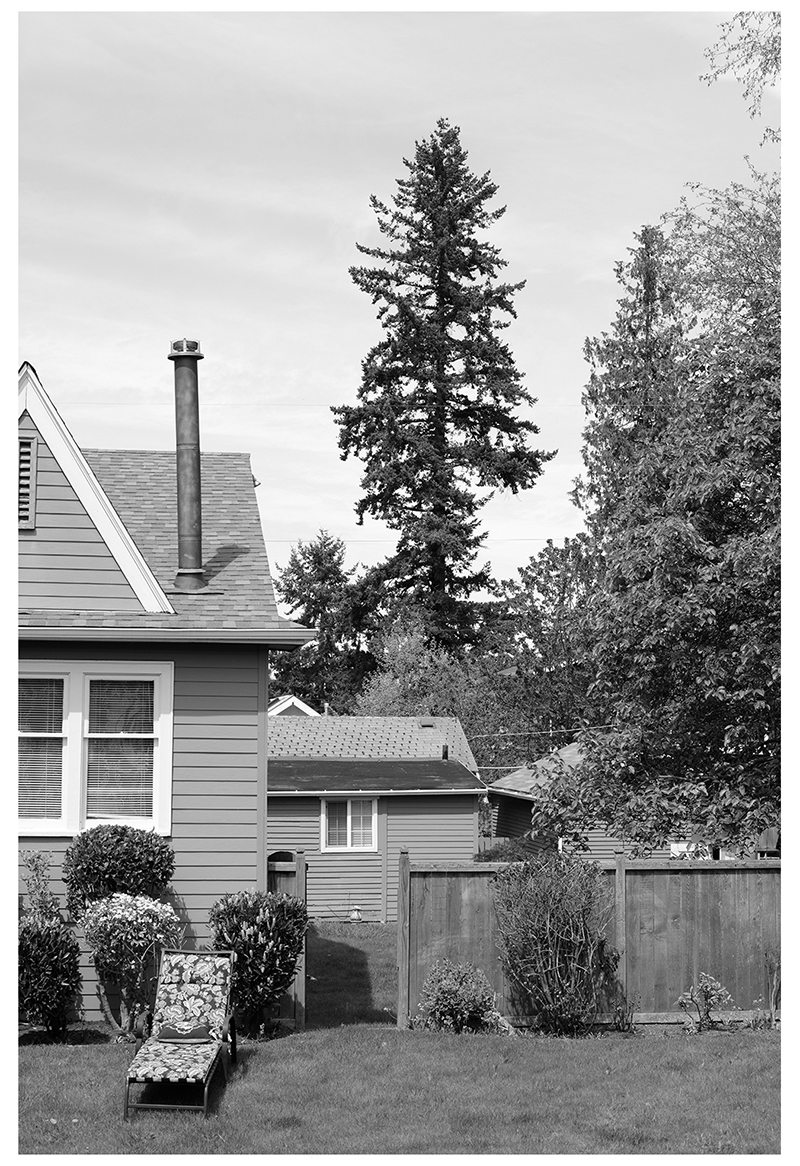

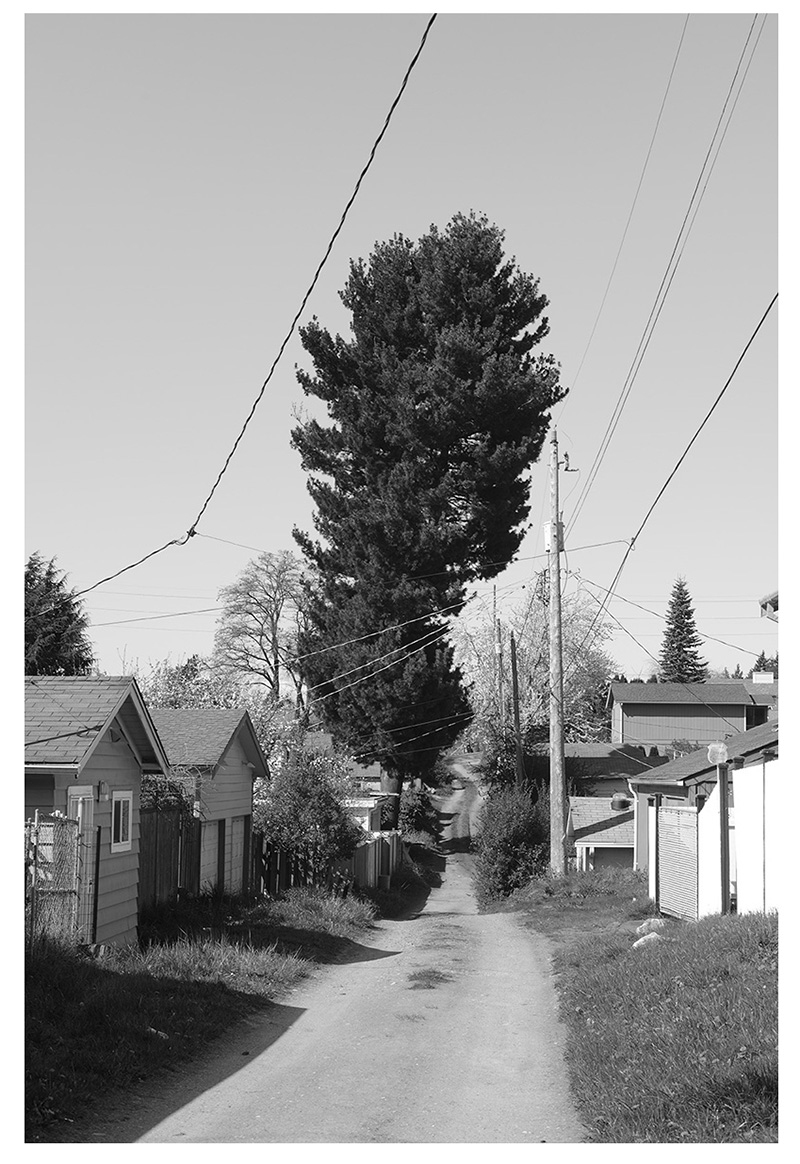

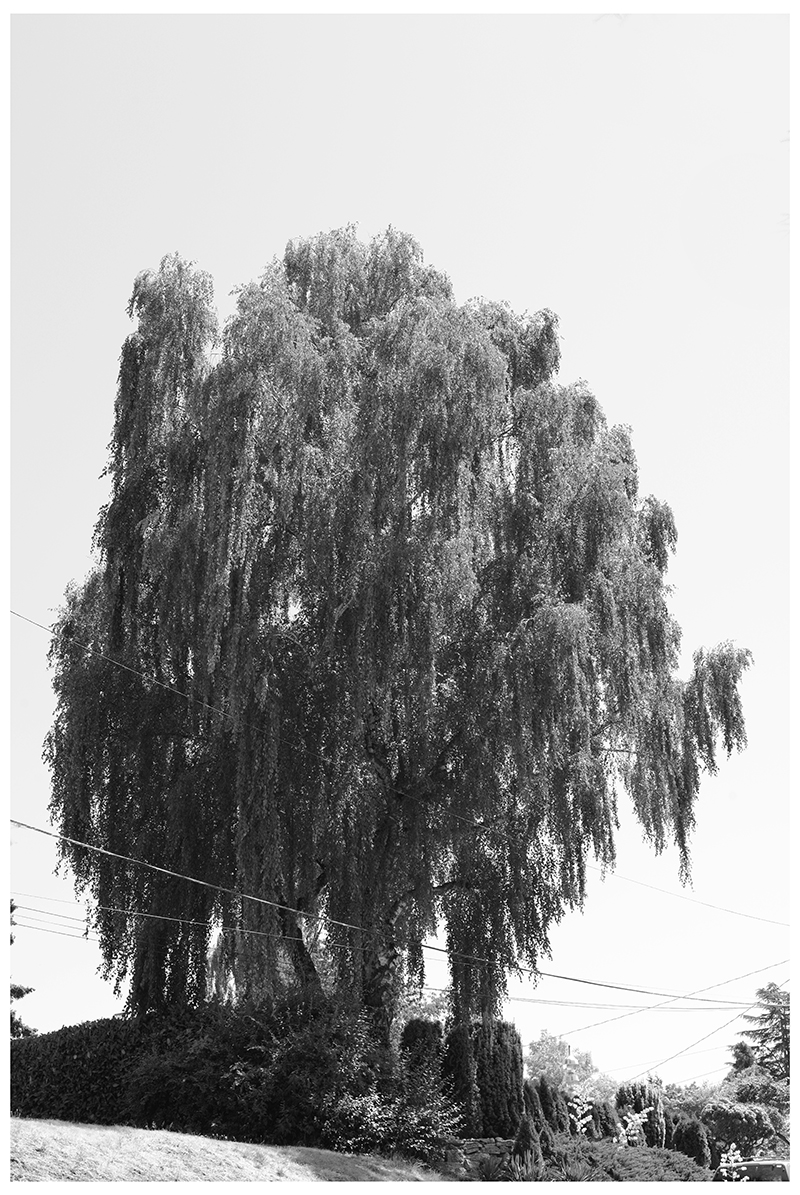

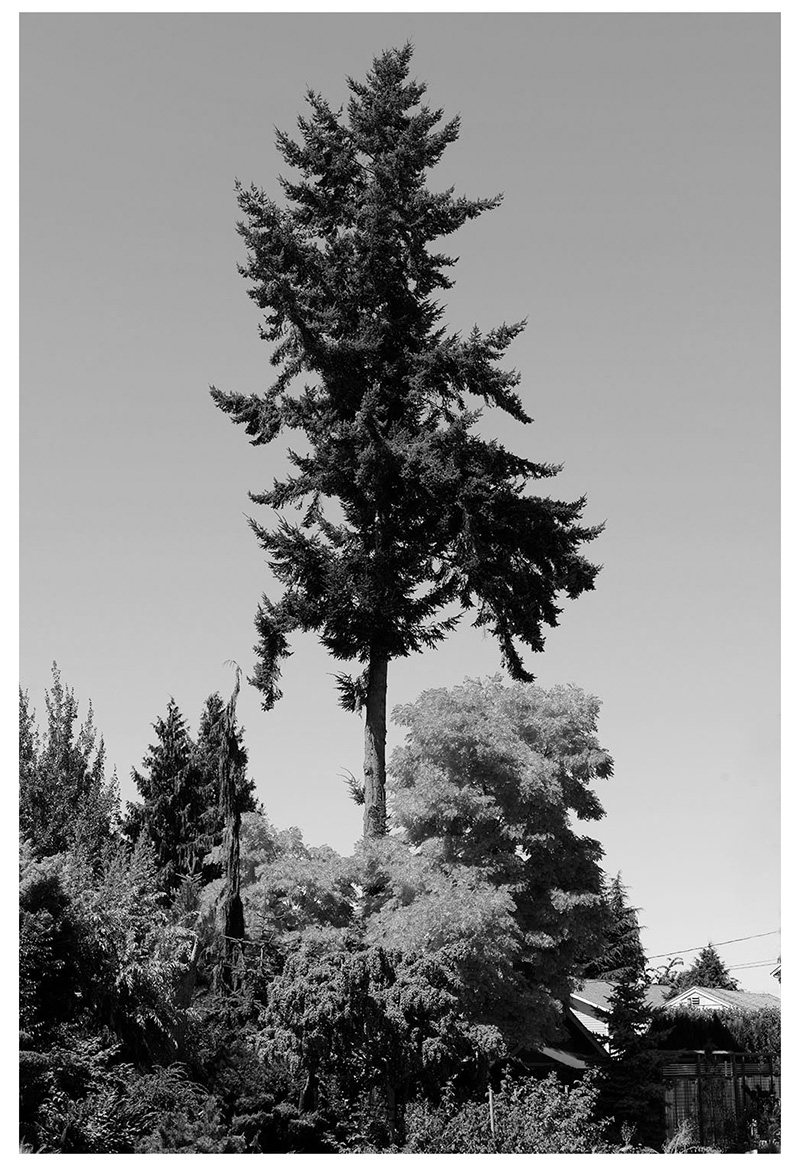

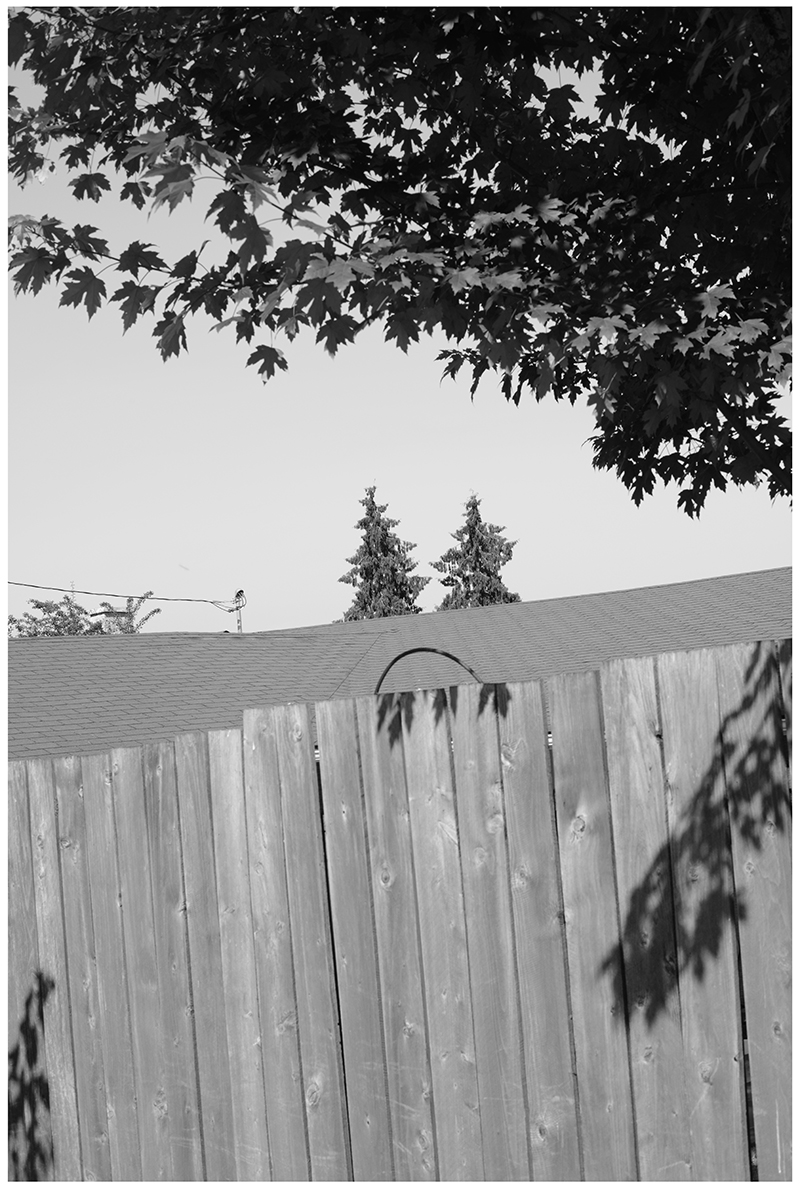

“Breathers” is an emotional portrait and near-typology of Pacific Northwest trees and their relationship to a developing landscape – a backdrop to the early onset of my mother-in-law’s Alzheimers. Trunks dart upward and hover over homes, set against skies that isolate them like studio backdrops. They have seen everything, heard everything and hang – breathing – through it all. This work processes a move and adaption from New York City’s mess of concrete to the Pacific Northwest’s proximity to fresh air, alongside the reasons for moving – a disease that’s claimed a rapidly vanishing memory, and the toll it’s taken on our family. In this context, the trees serve as listeners and emotional guardians that have witnessed trauma and change.

DS: Jon, tell us what sparked your interest in photography?

JF: Probably my dad. When I was around 6 or 7, we took a family vacation somewhere north of New York, and went on a few hikes through foggy woods. I remember my dad taking pictures of the fog and later getting “enlargements” (does anyone use that term aymore?), framing them, and hanging them around our apartment. Something about that, plus a exhibition poster of Edward Steichen’s “Heavy Roses” elevated how I saw photography – from simple family snapshots to “art” that could be in a gallery or museum. My first exposure to the more conceptual aspects of photography came from my sister, who, when I was in early high school, took me to see Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills exhibition at MoMa. I owe my writing to my mom who edited the hell out of likely every single paper I wrote in high school. Clearly there was a lot of family influence on everything I do. Haha.

DS: From looking at your different projects and bodies of work, what caught my eye was your use of ‘low’ and ‘high’ visual aesthetics – by that I mean, that it seems that you use different tools to capture your images yet they all seem to work well together. Can you tell us about these choices?

JF: There are a lot of self-proclaimed “Instagram influencers” posting mantras about the idea that “the best camera is the one that’s in front of you,” which I think is only partially true, and a bit pseudo-inspirational.

For me, it’s just about making pictures using whatever tool works best for the project in front of me. The best camera is the one that’s going to work best for the project (or individual photo) you’re trying to make. With my 2007-8 “Fast Food” series, that was a scanner, for its high resolution – almost like having a negative the size of the flatbed – and the scientific, specimen-like way it captured the food. With earlier series, it happened to be a large or medium format camera. With my latest project Breathers – photos of trees as Alzheimer’s metaphors – I’ve been using a digital SLR, though I tend to approach making these images with a similar kind of formalism and organization of space that I use when shooting with a view camera.

DS: Still life photography would be the category that I feel your images belong in. You find a way to capture moments that are unique because you decided to highlight them and convert them in to compositions that a viewer can enjoy and relate to. What is it about these objects in general that you gravitate towards?

JF: I never thought about it that way before, but that completely makes sense! My latest series, Breathers may technically look like landscape typologies, but I agree, they can be seen as still life photographs. I’m drawn to looking more closely at objects we’re used to passing by, to better understand them and experience their metaphorical possibilities. One of the first questions I often ask my Visual Literacy students when looking at images, is “how does this photograph make you feel?” – and in making these pictures with that kind of “still life” approach you describe, I hope they elicit some kind of emotional response beyond what one might normally tie to the objects, trees, or whatever it is in front of the camera.

DS: In your body of work Breathers you say that the project is “an emotional portrait” of trees that relate to your Mother-in-Law’s illness of Alzheimer’s. I found it interesting that you describe these trees as not only portraits but ‘emotional portraits’ – could you tell us more about this notion and the process around that course of thought?

JF: Great question. For me, there’s a deep sense of sadness in them.

This work processes a move and adaption from New York City’s concrete mess to the Pacific Northwest’s proximity to fresh air, alongside the reasons for moving – a disease that’s claimed a rapidly vanishing memory, and the toll it’s taken on our family. In this context, the trees serve as listeners and witnesses to trauma and change.

I’ve photographed strange trees for years, and for a while, was working on a “northwest vs southeast” photo conversation in trees with Lindsay Metivier for the online platform A New Nothing. But over the past year and a half, as my Mother-in-Law’s Alzheimer’s continued to worsen and make a permanent mark on my consciousness, I started seeing these trees as thick hosts for all the pain associated with it.

I haven’t organized these pictures in a specific sequential order (yet), but I started seeing parallels between gaps in the branches, holes between leaf patterns, areas where branches had been cropped prematurely, to different stages of prematurely deteriorating memory. The more I photograph them, the more they feel like giant sponges – absorbing, and retaining memory and pain. I’m sure I’ll make new associations as I continue to make this work.

DS: Many see black and white photographs as a visual of the past or of nostalgia – Can you tell us why you chose to use black and white photographs in this project?

JF: It’s interesting you bring that up – I was weary of that too at first, but think these are nostalgic and I’ve come to embrace it. Not like in the way the tv show “Stranger Things,” JNCO Jeans, or other 90s pop culture references distract us from the present, but my decision to present these in black and white relates to nostalgia for a time I never knew. When I first met my Mother-In-Law, she was already several years into the disease, already losing language and a huge chunk of memory.

I never got to know her before it began taking its toll, so there is sentimentality, or longing for that missed time. I should note that my own grandmother died of Alzheimer’s when I was a young child, and while I got to know her on some level, the memory of her is in small bits and pieces – the gefilte fish she made from scratch, her knowing who I was one year, and then having nor recognition a year later when we visited her in a nursing home, and various stories my parents have told about who she was, and how that faded.

DS: In general what is your workflow? What makes you feel like you took a good photograph? What would you never consider photographing?

JF: With this series specifically, it was a lot of aimless wandering. I was laid off from my job of 12+ years around the same time I really started going on this, which became a gift of sorts because it afforded me the time to spend making these pictures, going on extended hunts. It was (and continues to be) an incredibly meditative and therapeutic process. I’m not sure if that constitutes as workflow, but it’s some insight into my process on this series. As for a “good photo” – there have been plenty of images that I thought were my strongest when I shot them, but was unhappy with once I got them on a computer screen or made a print. So I think seeing and sitting with the final form is when I decide whether it’s a successful image.

DS: What would you say is your biggest struggle as a photographer, and how do you try and overcome it?

JF: For a while it was having the time between working full time, running Humble, and writing/curating independently, but, as I mentioned above, I think it’s really just about time management. Then a lot of self doubt, especially with so many photographer making work, and so many submission/rejection opportunities. Also, being able to turn what seems like a great idea into an actual project. There’s at the very least, 100 ideas for projects I’ve come up with over the past 5-10 years that I regret never actually pursuing. Finding time to just go out and do it, make the work.

DS: In addition to being an artist, you and Amani Olu have created a photography-dedicated platform that many of us follow and even submit work to, Humble Arts Foundation. Can you tell us what made you start this platform and what was its main mission back in 2005?

JF: We started Humble when we were both working at Shutterstock – our CEO introduced us for our shared interest in art photography. Amani had just moved from Philly and wanted to start something online that in some way responded to, or replicated the white-box gallery world. We started a project called “group show” – online group shows of 24 photographers each month with one image per photographer. The idea was that we would create a completely democratic platform in which photographers did not need to have family connections to the art world, a trust fund, or anything aside from the a great vision and aesthetic chops.

We began inviting former classmates, friends, and other acquaintances who were making interesting work and posted some open calls on Craigslist. We also wanted to find a way to elevate the work of “unknowns” so we cold-call invited a few “famous” photographers such as Alec Soth (around the time he was in the Whitney Biennial) and Todd Hido, who we thought could give these emerging photographers an opportunity to say they’d been in a show with.

We’ve had many forms over the years – brick and mortar exhibitions and collaborations with major auction houses like Phillips de Pury, two dense publications called “The Collectors Guide to New Art Photography,” grants, our recent book “Humble Cats” with Yoffy press and our continued online exhibitions and blog content. What drives it all is a commitment to getting new, often unseen photography in front of the folks who can make an impact on photographers careers.

DS : What is it like sifting through artist’s work as an artist yourself? I am sure that the act of rejection comes with some conflict as an active artist and the personal knowledge of the artistic struggles.

JF : It’s conflicted, challenging and inspiring all at once. With any open call I jury or curate, there’s a large pool of submissions that I have to reject just because there’s only so much room in the exhibition – even if it’s online. It’s likely that a significant percentage of those I reject, I actually think are strong, am moved by, etc and just can’t fit them in.

I’ve submitted my own work to several open calls over the past few months and been rejected from some, and accepted into some. So I know first hand how awful it feels to have work “not make the cut,” to feel slighted, and to have self-doubt. Being a curator and juror of many exhibitions helps me move past this stage relatively quickly and understand that it’s not personal and not always a reflection of unsuccessful work – jurors have a ton of submissions to wade through.

DS : Since you see so much work with all of the various hats you wear – how would you describe today’s photography scene?

JF : I think I would describe it – in your words – as “various hats.” Photography is splintered and evolving – both technically and conceptually – faster than ever before. I think it’s difficult to pinpoint, and is perhaps (for me) the best description of its current state.

DS : What is the best advice you can give to fellow artists and photographers?

JF : Here’s a top ten:

1) Keep making work.

2) Join a crit group with artists you respect and trust.

3) Pursue every idea you have or you’ll regret it later.

4) Be self aware – don’t be defensive.

5) Stop fearing the dreaded artist statement. It can help you think more clearly about what and why you photograph. That said – avoid the word “explore” like the hand of death itself.

6) Rejection isn’t personal – if you get rejected from an open call, take a breath, scream in a pillow, and get back to making work.

7) Email curators, writers, gallerists who you admire (and seem to have a taste for the kind of work you make) to get them familiar with your work.

8) Don’t be dismayed if you don’t hear back right away – people are incredibly busy. If they’re moved by your work, they’ll get back to you.

9) Be gracious of people’s time – say thank you.

10) Support your fellow artists – champion work you believe in.

To view more of Jon Feinstein’s work please visit his website.

Details :

8.25″x10.75″, 256 pages,

Perfect Bound

Edition Size 1500

ISBN : 978-1-944005-18-4

Printed in the Netherlands

Introduction by : The Editors

Guest Curators and Interviews by :

Alan Rothschild

Amy Elkins

Anna Skillman

Heavy Collective

Jennifer Murray

Kris Graves

Michael Itkoff

Paloma Shutes

Paul Kopeikin

Rachel Reese

Robert Lyons

Small Talk Collective

Susan Laney

Zemie Barr