Deborah Orloff is a Professor and Associate Chair of the Department of Art at the University of Toledo. She teaches all levels of Photographic Art at UT’s Center for Visual Arts, and has been a professional artist for over 20 years. Originally from New York City, Orloff received her MFA from Syracuse University and her BFA from Clark University. Although her primary medium is photography, she has also worked in video and installation. Her artwork has been included in numerous exhibitions at national and international venues including: the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City; the Toyohashi Museum of Art & History in Toyohashi, Japan; and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, Scotland. Her current series, Elusive Memory, was included at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography as part of their Midwest Photographers Project. Deborah Orloff has been the recipient of dozens of grants and awards including corporate sponsorship by Hahnemühle Paper and the Ohio Arts Council’s 2019 Individual Excellence Award.

Are our memories our own? Deborah Orloff’s mysterious photographs of photographs – with their illusory juxtapositions and otherworldly details – meditate on this exact question. Her work imagines potential narratives, encouraging us to question our predisposition with information in an era contrived of images. I recently had the privilege to connect with Deborah over her most recent body of work “Elusive Memory”. In this interview, we engage in a discussion on photographic representation, memory and objecthood as such themes surface in this compelling body of work.

Elusive Memory

In America, the photographer is not simply the person who records the past, but the one who invents it … – Susan Sontag

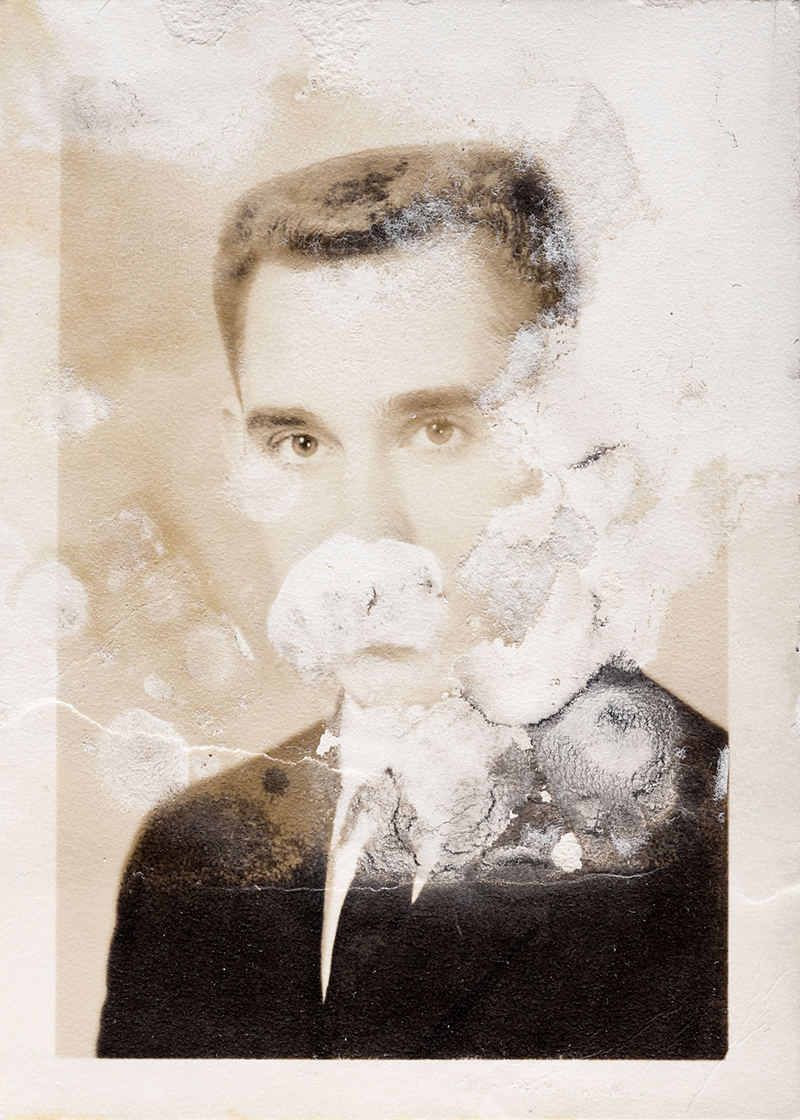

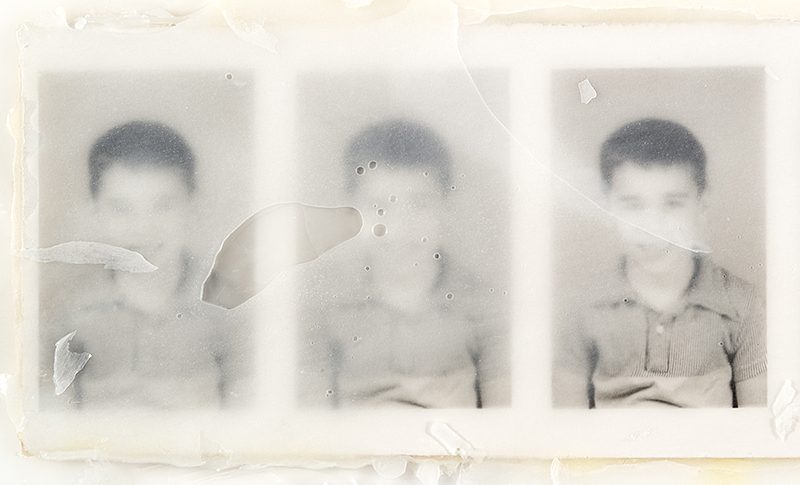

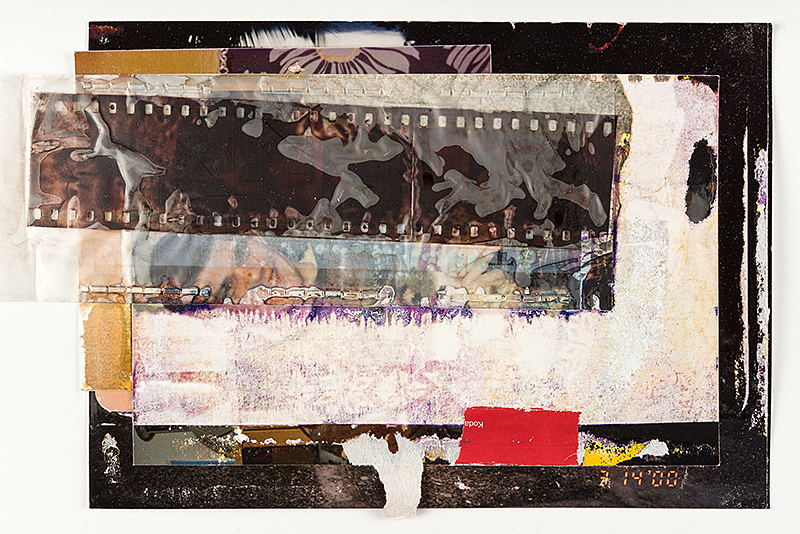

The relationship between photography and memory is complicated; it is dubious at best. Do we remember our past? Or is it the photographs we have seen so many times that retain these memories for us? I have always been fascinated with family photos and have collected them most of my life. Recently, I’ve been drawn to the abandoned pictures that were relegated to my parents’ basement. These once precious objects have been neglected and forgotten. Inadvertently exposed to water, heat, and humidity, they have undergone a powerful transformation. My new work utilizes these severely damaged pictures as subject matter. Elusive Memory explores the significance of vernacular photographs as aesthetic objects and cultural artifacts. The resulting large-scale photographs make commonplace objects monumental and emphasize their unique details. In their final representation, these banal objects become simulacra of loss and speak to the ephemeral nature of memory.

Kyra Schmidt: Deborah, I am delighted that we could connect with you at SPE. Your photographic series, Elusive Memory, explores complexities between photography, memory, representation, and objecthood. Could you talk about the path that lead you to found imagery? What makes this process of repurposing old photographs then highlighting their thingness important for you?

Deborah Orloff: I had been thinking about the connection between photography and memory since my father’s death in 2007. As I was writing his eulogy, I realized that just about every memory I had of him was connected to a photograph. The more I thought about it, the more I wondered if I remembered these moments at all, or if the pictures had created false memories. I wanted to make work about this phenomenon, but the project didn’t actually take form until many years later. About 5 years ago, I inherited thousands of neglected prints and slides that had been in my father’s basement where they were damaged by flooding. I started photographing them in the studio, not knowing what I would do with the images, but hoping to salvage some of the family pictures for posterity. It wasn’t until I saw them enlarged on a computer screen that I recognized their poignancy and greater relevance; I saw metaphors for loss and the fragmentary, ephemeral nature of memory. I was also intrigued by their strange beauty and significance as cultural artifacts. So much of their symbolic quality resonated for me.

KS: I think that your discussion of the photograph as cultural artifact and aesthetic object highlights the medium’s slippery, discursive nature. As a heuristic device, photography’s material forms, enhanced by its presentational forms, are central to the function of photographs as socially salient objects – and these material forms exist in dialogue with the image itself to make meaning. I’ve noticed that you further assert the photograph as object in their physical layering. What brought about this aesthetic decision?

DO: As you point out, photography encourages exploration and discovery but the layering only makes visible bits of visual information and clues (date stamps, curtains, parts of faces, clothing) to be deciphered. The layers hide important details including the subjects’ identities. Yet, they simultaneously add a sense of mystery as we ponder the hidden images and try to make sense of the signifiers. Ironically, the very device that thwarts recognition also encourages us to look more carefully; it elevates our curiosity and allows us to discover more.

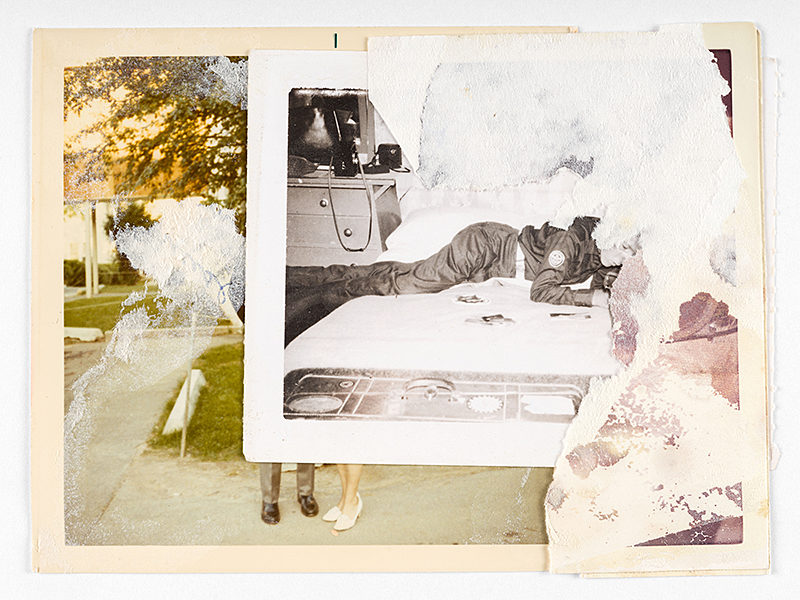

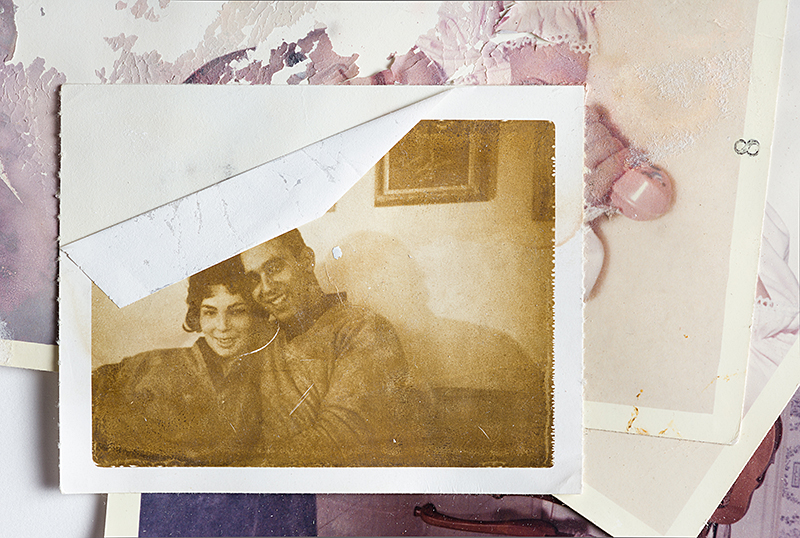

When I first found the damaged photos, many of them were stuck together and I photographed some of these small assemblages. I had to make aesthetic and conceptual choices about how much to include in the frame, but I loved they way I initially saw a chaotic mass of information that revealed itself layer by layer. In some cases, I was able to recognize part of a picture from family albums I’d seen growing up, but more often than not, the layers were permanently sealed and there was no way to know their contents. That of course contradicts so many ontological notions about photography and its relationship with reality. We expect to know what we’re seeing when we look at a photograph, so that denied gratification is especially intriguing to me.

After making photographs of pictures that were stuck together, I started experimenting with my own layering. I’m especially interested in the random juxtaposition of unrelated pictures that imbue the composition with new meaning. For example, in Writing Home, a young man appears to be lying on a bed writing letters. His surroundings and clothing suggest he may be at a Boy Scout camp, in which case he could be writing to his parents. The color photograph underneath only reveals an anonymous couple’s feet. They’re probably not his parents but we can’t help making the connection.

KS: The photographic medium has a unique way about it that enables its ongoing reorganization of our mental and physical landscape, you highlight this in your artist statement. These found snapshots start to become talismans of recollection, but then our “window” is suddenly disrupted by stains, scratches, or decay. The photographic material reasserts itself. Why have you chosen to highlight these unique details?

DO: My images become simulacra for the experience of remembering. We often recall people and events in bits and pieces; some parts may be clear while other aspects are obfuscated, or we see a vague image in our minds with important details veiled or missing altogether. On another level, emphasizing the decay underscores the fact that we are looking at objects with their own history. In the 1950s and 60s, when most of these pictures originated, people didn’t document every moment of their lives the way we do now. Pictures were made when there was something important to mark. The photographs were precious. They were held in someone’s hand, carried in a wallet, or maybe framed and displayed. But now these abandoned objects have been transformed by the effects of time and negligence, and in spite of a sort of violence that’s been enacted upon them, there’s something beautiful about the textures and details that have emerged. The enlarged surfaces look more like peeling paint or frescoes than photographic prints. They have a physicality and a presence – unlike today’s vernacular pictures which are seldom printed.

KS: You are completely right, in an era that is increasingly digital, the majority of photographic images are viewed on a screen rather than as physical objects. Do you think these material changes in the nature and practice of photography will alter society’s relationship to memory?

DO: That’s a great question. I do think the nature and our practice of photography is changing our relationship to memory. Everyone who owns a phone has a camera and we clearly generate more photos than ever. On one hand, you could argue that taking so many photos reinforces memory. However, with the pervasiveness of digital technology, instead of trying to commit things to memory, we tend to pull out our phone and snap a picture, hardly paying attention to what we’re shooting. The visual reference is stored for potential use. We even use our cameras to take “notes” now. It’s certainly efficient, but I think it gives us license to forget as we’re not fully present in the moment. Instead of experiencing places and events we take photos, that we may never look at, often without really stopping. How can we expect to remember anything beyond the superficial? We process an overwhelming quantity of visual material daily, but we really don’t see most of it.

KS: Certainly, this transformation has enabled photographs to reach a wider audience than ever before and yet, somehow it’s as if this ubiquity has left us less informed or less aware. As you highlight in your artist statement, (we) rely on photographs to preserve memory. Susan Sontag would argue in unison “photographs supplant and corrupt the past, all the while creating their memories.” Does this fact of the photographic distress you?

DO: Actually, it does! I can’t help wondering if I really remember my past or I just know the photographs – which fabricate “memories.” My Favorite Dress is a perfect example. When I first came across the damaged photo of myself in nursery school wearing a gray velvet dress, I immediately smiled and thought “That was my favorite dress!” I even remembered the pink satin bow that’s no longer visible in the image. Then I realized how unlikely it would be to remember a garment I wore when I was four years old. Over the years, I had seen photos (that were not damaged) of myself in that dress and I know my mother told me repeatedly how much I loved it. Realistically, the repetition of her stories, along with regular exposure to family pictures, created an artificial memory of the dress and my nostalgia for it.

Similarly, the focal point of my installation, Threads, is a manipulated photograph of a folded, hand-written letter. The writing, while visible through the paper, is faint and illegible. I found the letter in a trunk of memorabilia I hadn’t seen for many years. When I read the letter – which was quite heartfelt and personal, I had no recollection of the author. That was quite distressing as I obviously had some relationship with this person. The experience made me wonder if I will eventually forget everything that lacks a photographic “prompt.”

KS: Baudrillard would agree with you (as would I), arguing that we have lost all ability to make sense of the distinction between nature and artifice – there is only the simulacrum. Do you think there is any coming back from this contemporary state of distraction?

DO: It’s ironic that you ask that because people often assume this work is manipulated. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked what my process is. When I say “they’re photographs” I get really perplexed reactions. In all fairness, my last two bodies of work were digital photomontages so maybe that contributes to the assumption, but I love the fact that that my images don’t always read as straight photographs. For the record, I am shooting the objects you see with a camera and studio lighting. The trompe-l’oeil effect I achieve, which often misleads people to think the pieces are mixed media and physical collage, is accomplished through the lighting. I do make minor enhancements in post-production but I’m not creating the content on the computer; everything you see was in front of the camera.

We’ve been theorizing about the veracity of photography for decades, and we all know that photographs are manipulated, but I think we’re at a critical juncture in which many of us are starting to assume a photographic image is manipulated before we consider the possibility that it’s not. And yet, we don’t think about how much the images we see in the media, that are meant to look “straight,” are actually altered. So in addition to the uncertainty of the photographic memory, the reliability of the medium itself is called into question. I guess we are stuck in a “contemporary state of distraction.”

KS: What is in store for you this year?

DO: Right now I’m getting ready for a solo exhibition that’s coming up in May at WorkSpace Gallery in Lincoln, Nebraska. I’m also giving a talk about my work at the Clinton Arts Center in Clinton, Michigan as part of their speaker series on April 28th. Shortly after I return from Nebraska, I’ll be spending a week in New York City (where I’m from), and then traveling to South America for a few weeks.

I’m extremely honored to be the recipient of the Ohio Arts Council’s Individual Excellence Award, and will be using the rest of the summer to make new work with the grant. I’ll also be gearing up for 2 more shows: a solo exhibition at Youngstown State University’s Solomon Gallery in October, and a 2-person show with Kris Sanford at the Shircliff Gallery at Vincennes University in February.

KS: This all sounds fantastic. I think we are all looking forward to see the results of this new work from your grant! Before we part ways, and as a seasoned Professor of photography, are there any words of advice or encouragement you might offer the emerging artist?

Thanks! The best advice I can give is really quite simple: work hard, be true to yourself, and follow your passion relentlessly!

To view more of Deborah Orloff’s work please visit her website.