Olga Bushkova (1988) was born and grew up in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, now is a Zurich-based artist.

Graduated from Rostov State University with a Master degree in Applied Math, she began working with photography, both artistically and commercially, in 2011 when she and her partner moved to Zurich, Switzerland. To date Olga has produced two photo projects A Google Wife (book published by Dalpine), and How I tried to convince my husband to have children (to be published by Witty Books). Olga’s books have been shortlisted or awarded at such festivals like: Prix Photoforum, Images Vevey Photobook Award, Unseen Dummy Award, FLIP Photobook Award, Author Book Reward at Les Rencontres de la Photographie, Fiebre Dummy Award, Photoboox Award etc.

How I tried to convince my husband to have children

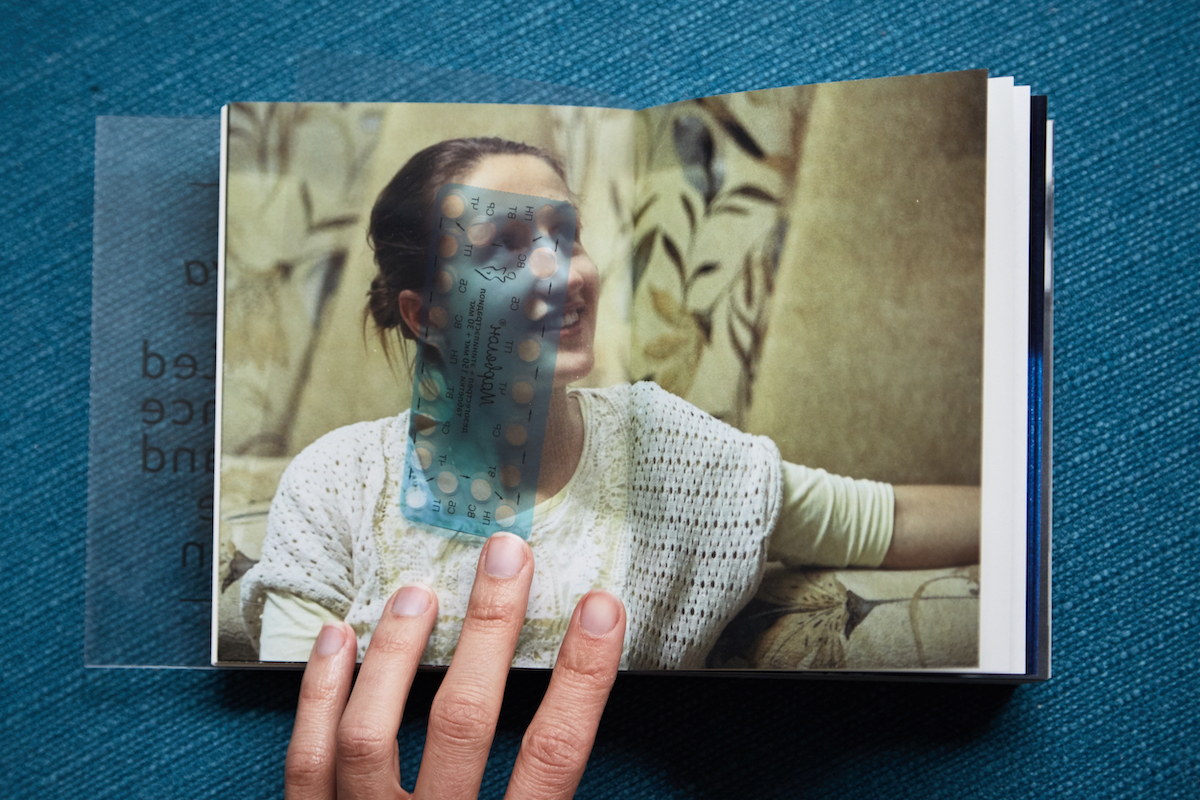

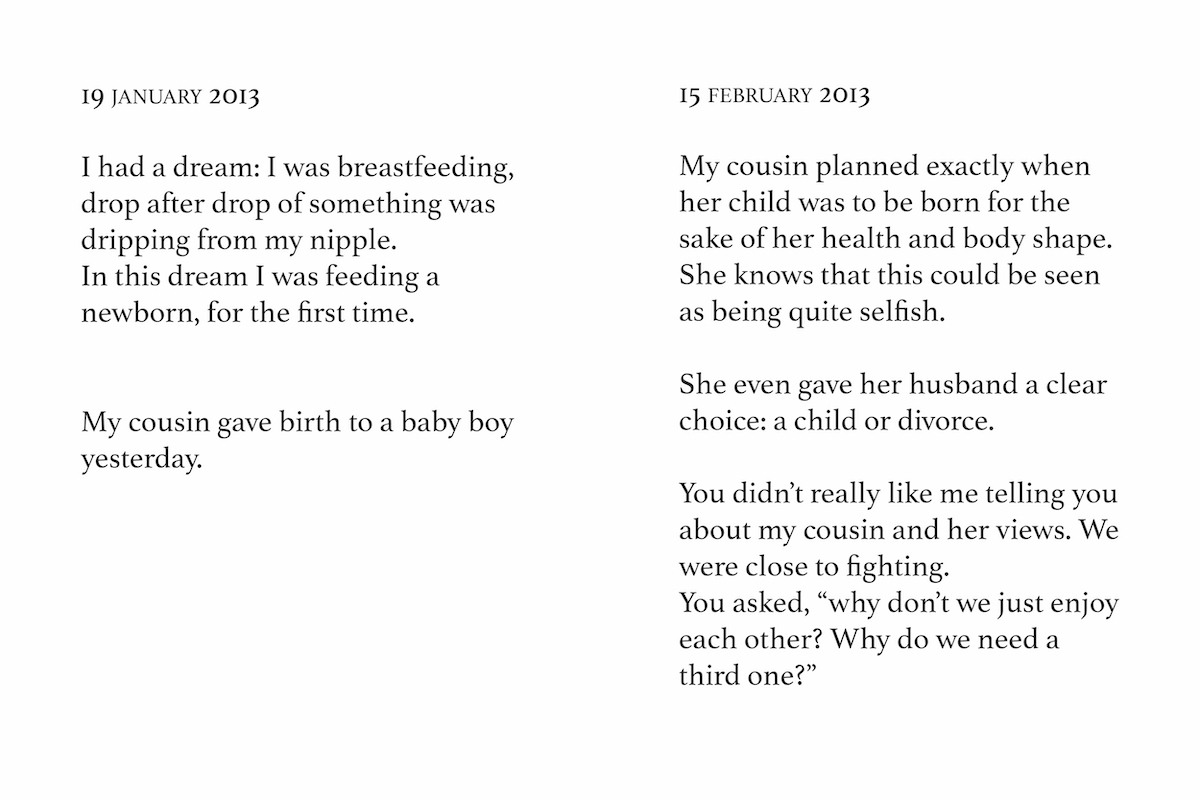

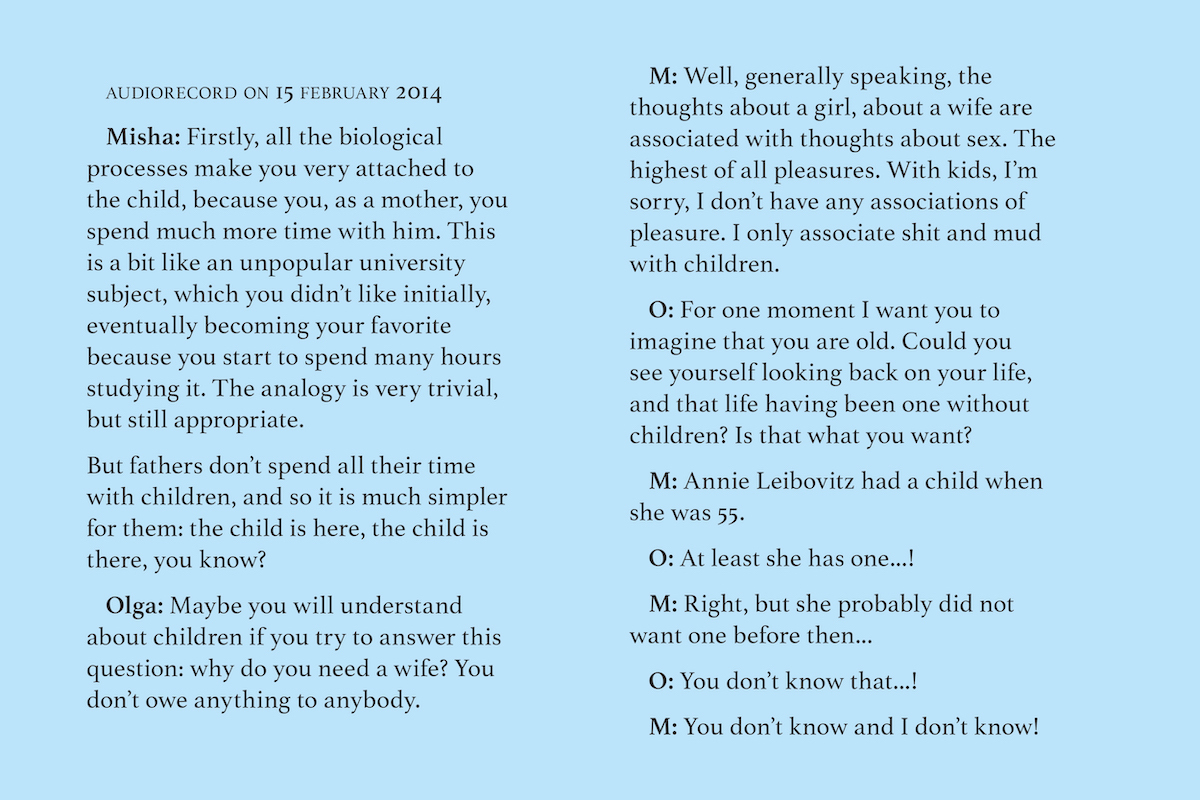

How I tried to convince my husband to have children is an autobiographical book about a woman’s obsession with becoming mother and her constant discussions with her partner in order to convince him. Through a powerful visual narrative using mixed- media approach, combining photography with private diaries and conversations recordings, Olga Bushkova tells a bittersweet and moving story of a woman and her relationships with herself, her partner and the world, and how communication can sometimes be more important than finding answers.

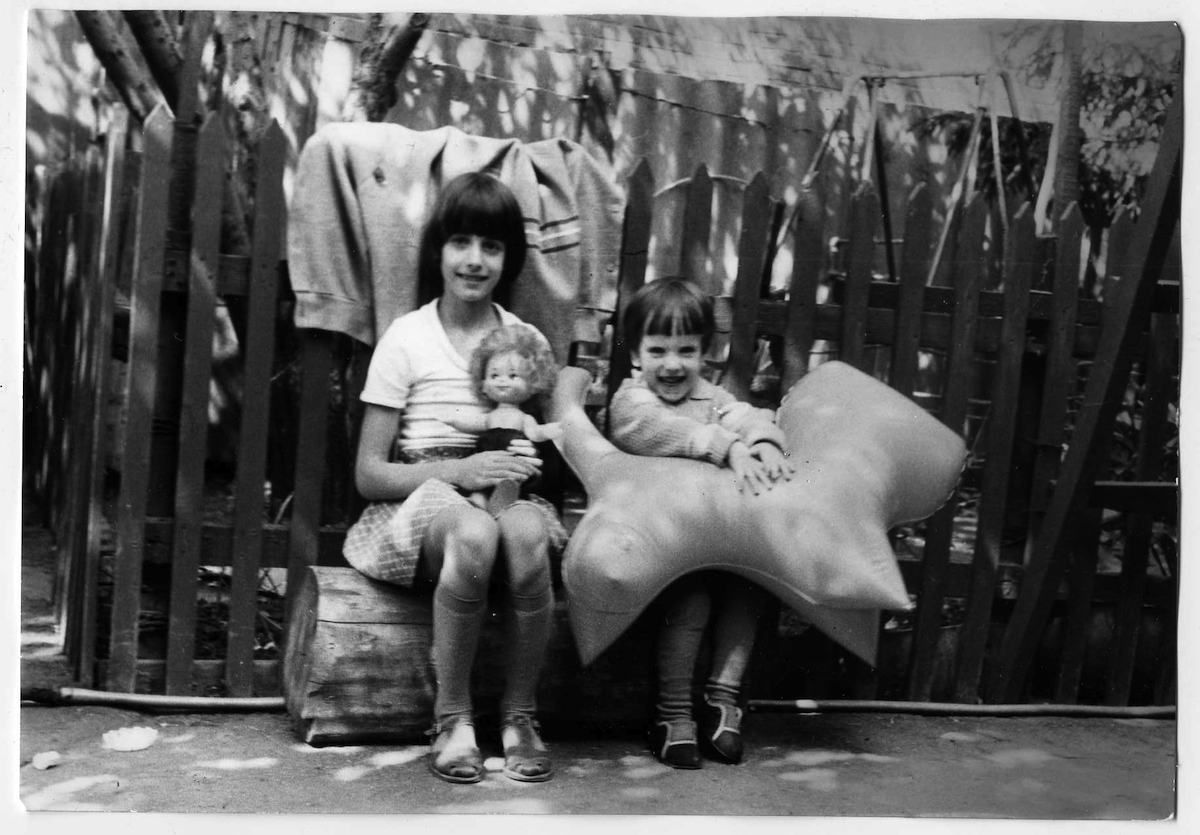

“Is it just me or do you also discuss with your partner whether to have children or not? If so, then how many children? When? Why? Where does this idea to have them come from at all? I didn’t ask these questions myself when I was young. I always wanted to be a mother. I was always obsessed with children. Until I got married and understood that my husband had a different opinion. That he does ask those questions. He always offered rational arguments against the idea. His biggest argument was that women run the risk of turning into housewives if they become mothers before establishing themselves professionally. From 2008 onwards we had endless discussions about whether or not to have kids. I captured this journey in my book How I tried to convince my husband to have children. It includes photos, diaries, transcripts of dialogues with my husband and our archival pictures. It presents a dialogue between two opposite worlds, his and mine. The story in the book is not simply about children – it is about a couple, its struggles, aspirations and disappointments. ” – Olga Bushkova

The project has been completed in the form of a book dummy and is due to be published by the Italian publisher Witty Books in Spring 2020.

Claudia Bigongiari : How I tried to convince my husband to have children is a three year documentation about your couple life and the different position of having or not kids, that you defined as an obsession. Why do you think you’ve been obsessed with this idea? It was the difference between you and same age mothers and previous generations, or something else?

Olga Bushkova: You know, I was pretty much always drawn to children. I’m really interested in them. I like to observe how they behave, how their logic functions, their character builds. I like to talk and interact with them. I have been into children psychology books since I was a teenager. And I mean not only popular psychology books, but also Lord of Flies by William Golding or To kill a mockingbird by Harper Lee, Scarecrow by Vladimir Zheleznikov (later made into a brilliant late-Soviet movie Scarecrow by R. Bykov).

For me the idea of having children was always a part of life. It was never discussed in my family. But then I got married and my husband had a different opinion. He was asking tons of questions – why? what for? do you really want it? Thing is: my parents got married when my mother was 20 and I was born when she was 22. I also got married when I was 20 and by 22 I could feel the clocks ticking. My brother was born when my mother was 27. So after I turned 27, the desire to have children became a proper obsession. I turned 27 in 2015, I didn’t have children and I was still working on the dummy of the book. Nearly all my friends had children already. And they grow so fast! And then my friends got a second kid, a third kid. There were more and more children around. The hardest part was to see somebody pregnant. That acted as a constant reminder to me: this woman will have a baby soon and I’m still on a contraceptive pill – the clocks are ticking.

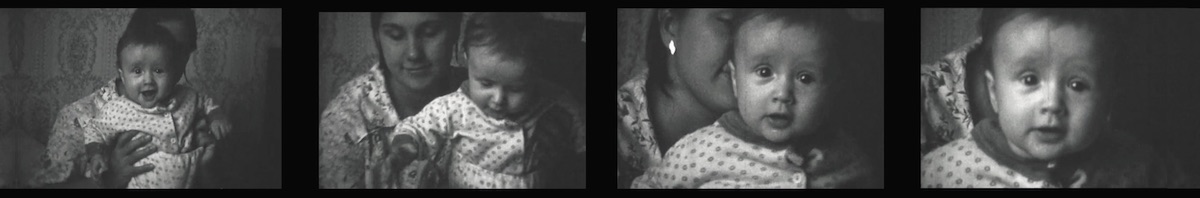

CB: Since 2012 you started putting together images of your friends’ kids, old pictures from yours and your husband childhood, transcripts of your dialogues recorded during the continuous discussions about having children. How this idea of ‘archive’ came out and what did you expected when you started?

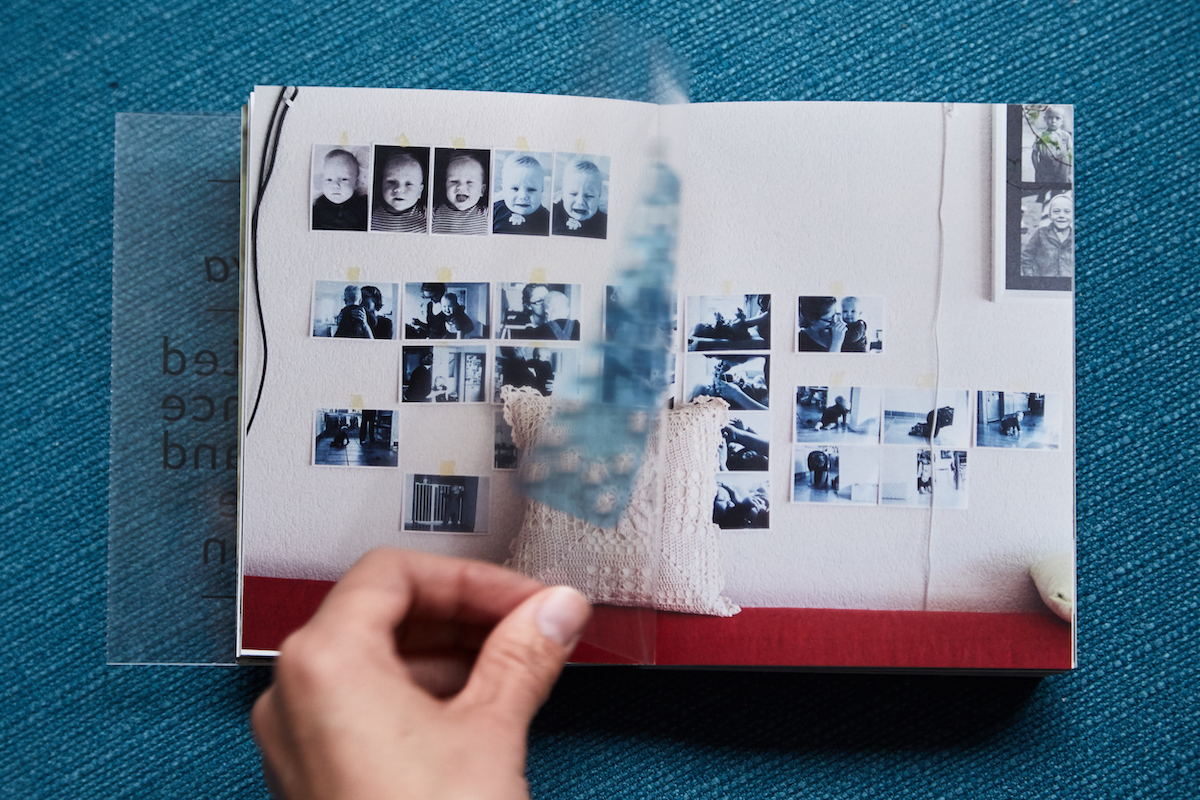

OB: In 2012, following a suggestion by Alex Majoli, I started to collect all materials related to my desire of having children. I wanted to express my attitude, because my husband was making these very rational arguments and I couldn’t counter these arguments in a logical way. I had to find a way to express the irrational part of my desire. To let him feel it. I was constantly photographing my friends, their newborns, their older kids. Gradually, photography became an instrument I used to interact with children, to understand them better. I was printing the pictures and hanging them on walls at our place. Then I was taking a picture off the wall and replacing the with new ones. It was important for me to let my husband feel what I was feeling.

Of course, it was a bit naive to think that he’d want to have a child after looking at other peoples’ kids. But I felt it was worth trying. Also, I got his childhood photographs from his mother and used them on the walls too. So it wasn’t only random kids. He was there too, on that wall, as a small child together with his young parents. I wanted him to see that. We talked a lot. About children, fears, expectations, goals… and it soon became clear that these dialogs had to be documented as well.

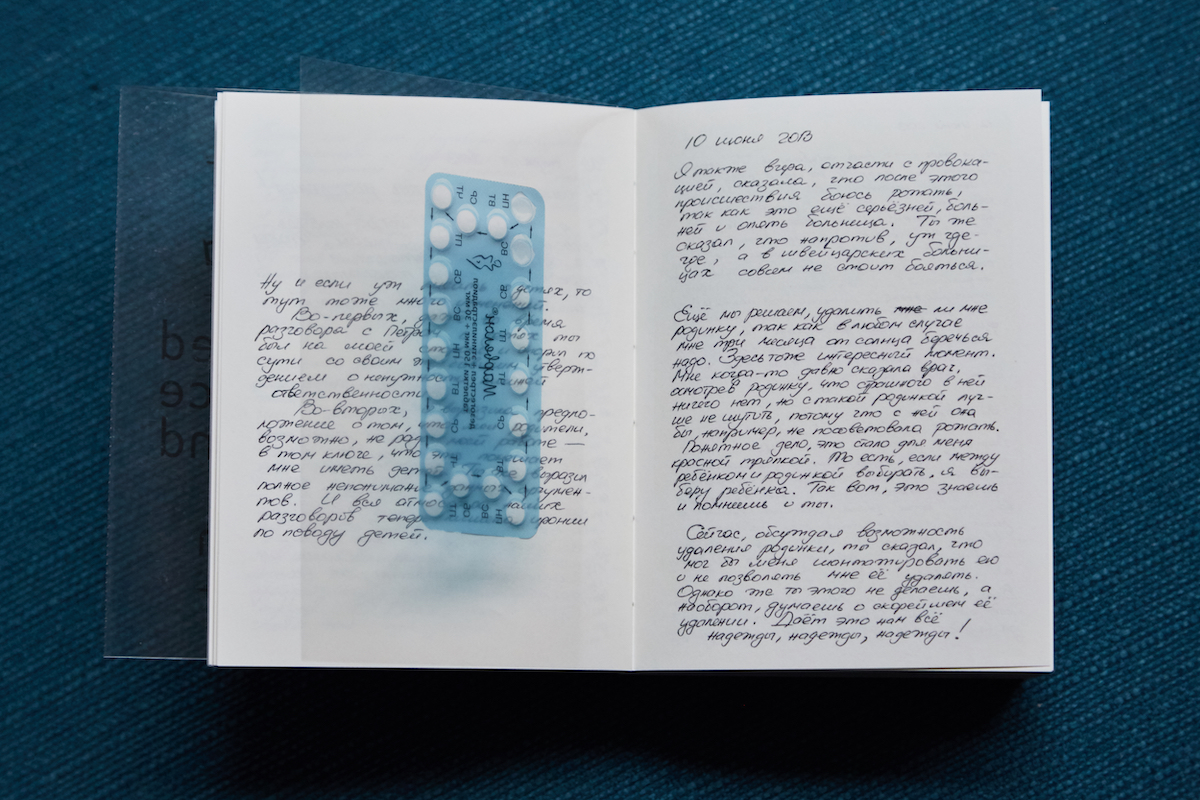

Finally, there were my own thoughts, my personal observations – the hardest thing for me to document, since I can’t photograph my mind. I started to keep a diary. At the beginning I really believed that I would convince my husband. But it didn’t work. Instead we made a playful deal: if I made a decent book out of all the documentation that I was assembling, then he’d have agreed with me to stop taking the contraceptive pill. My husband really wanted me to grow into being an artist, he was ready to take the risk.

CB: Something that made me reflect about your story is when your husband was telling you that if women become mothers they will turn into housewives before establishing themselves professionally. This is, I think, a still delicate argument: to attempt to combine professional and private spheres, or worse, to give up the career for a ‘domestic life’. What is your position, as woman and photographer, about that?

OB: He has indeed always offered rational arguments against the idea. His biggest argument was just that: women run the risk of turning into housewives if they become mothers before establishing themselves professionally. In his case all this is rooted in fear, fear of the unknown. If we get a child, what would happen to our relationships? How would I change? I think he wanted me to develop as an artist, because for him this would be more understandable, known and predictable – he’s a photographer himself. I personally was always sure that I could handle everything: both the child and the professional development. I was sure that having a child is not an obstacle. A child is just a part of the family, and family is not a problem for professional development.

The reality, however, is more complicated. When you get a child, you get a new perspective on practically everything, but you have very little time. Everything goes faster and you feel like you’re in a car without brakes, you can steer left or right, but you can’t stop. What I needed in this kind of moment is self-confidence. The fact that I studied, worked and fulfilled a number of personal ambitions helped me to stay confident that everything will be alright. My parents always worked a lot – before they got kids and after. For me it’s important that a child knows that his parents have other interests in life, and some skills. My mother, for example, worked as a shoe maker. When I was a child I overheard a conversation and realised that my mother was very good at making new experimental models and helping designers to put experimental stuff into production. I remembered how much I was proud of this. I think if a child knows that his mother is good at something, it will help him to be curious in life too. In the end, I’d admit that my husband was right to a certain extent: the timing we eventually chose was right, and it helped me realise two very important projects as an artist, so now I’m happy to be a mother and a photographer.

CB: Another very interesting element is the diaristic part, so intimate and personal but, at the same time, a universal conversation to everybody struggling in their relationships. Did it help to express yourself through the diary, maybe even more directly than with pictures? And do you believe in photography as a therapeutic medium?

OB: It’s true that the book is less about children per se and more a documentation of relationships. It’s about how a couple goes through a fundamental conflict. Everything in protagonists’ relationship becomes important: how they talk, how they try to express things that are hard to express, fear of changes, or an irrational dream. What do they feel? What ways do they find?Writing a diary for me was very hard. I prefer to talk, not to write. When I write, the texts come out naive, almost dreamy. Initially what was tough for me was to re-read myself. It became easier when I “took distance” from the story and started to look at Olga as the protagonist in the book and not the real me. I just accepted that the Olga in the book is naive, stubborn and dreamy. It’s good. She’s consistent.The photos let you feel how obsessed she is. She’s really focused on one thing: children. Even the way she sees them is naive and dreamy.

The text compliments this setting, provides depth to the story – you learn about her thoughts and motivations. Text and pictures in the book are not parallel, they intertwine and build the story together. I think that only text without pictures wouldn’t work. And pictures do not stand well on their own. When you mix them together, things get interesting. I think that photography can be a therapeutic medium, but I see it a bit differently. I use it as an instrument, a tool to understand myself and the world outside. But also – in the context of the book – a practical tool to fulfil my dream and become a mother. In that sense my relationship with photography is more practical than therapeutical.

CB: How I tried to convince my husband to have children has become a book, where every four pages there is a picture of your contraceptive pill package, beating the time. One picture for each pill taken, almost as obsessive as your willing of being mother. Can you tell us something about it? About this beat of time that is always perceivable.

OB: I started to take contraceptive pills before I got married, as a recommendation from my gynaecologist. A pill is an interesting phenomenon: it has an innate quality of rhythm, a countdown. 21+7, 21+7, 21+7. Stopping to take a pill is not an easy decision. To stop taking them means – ok, now I’m starting to make children. My husband didn’t want to leave anything to chance. He asked me every evening, if I had taken my pill. If he forgot to ask in the evening, he’d ask in the morning. If he forgot to ask in the morning he’d send me a message from work. I began to photograph the pills every evening, as a reminder that I took them.

When I included the pills into the first book dummy, they were inserted between the pages and some reviewers complained that they’re too distracting, that they interfere with the other pictures. I realised that this is exactly the point – they have to interfere! Just like they interfered with my desire to become a mother. I wanted to force the reader to do a periodical action: every time he sees a transparency with the pill picture, the reader must turn the page. Just like I was doing an action every evening by taking the pills.

CB: One last question Olga, visually speaking, which are your sources of inspiration? Do you have something in mind for the future that you would like to share with us?

OB: Oh, there are many inspiring things that I can name. When I’m completely stuck, I tend to look at Sophie Calle’s work. I mean, I may be influenced by a number of artists, but she is the one that I feel I truly connected with. For me it’s always important to see how she makes the work, what kind of solutions she finds. For her, photography is not the absolute goal, it’s just an instrument. Also, most of her work is about herself, she doesn’t simply observe, she is also a performer, a researcher. There are also photos made by non-professional photographers that I find inspiring. For example, for the last four years I’m exchanging photos with my father. We send each other a single picture at the same time, each day. For me it was funny to see that my father takes better pictures than I do. Maybe because he doesn’t try to conceptualise and simply enjoys the moment and wants to share it. His pictures are sometimes sad, sometimes joyful. He photographs everywhere: in the hospital, at friends’ place, at work. I enjoy this kind of connection that we have through photography. Then there’s also a book Art as a therapy by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong. It helped me a number of times to get through my down moments – when I felt like shit and I was questioning what art is for and whether I should continue to do photography at all.

As for plans: we have a few collaborative projects in the works with my husband. We postponed them for quite a while because we both were busy with other things, but now, as soon as How I tried to convince my husband to have children gets published, we’ll start working on them again. My husband is a very different kind of photographer than I am: his pictures are like poems, there’s so much love in them. I don’t know how he makes them.

Thank you so much Olga for sharing your time with us!

To view more of Olga Bushkova’s work please visit her website.