Doug Fogelson studied at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Columbia College Chicago. His photographic works are included in collections at The J. Paul Getty Center, The Museum of Contemporary Photography, The Cleveland Clinic, and have been exhibited at the Chicago Cultural Center, Walker Art Center, Marlborough Chelsea, Museum Belvedere, Netherlands, the 69th Street Station on the CTA Red Line in Chicago and via various public/private collections. Doug is represented by Sasha Wolf Projects in NYC and Linda Warren Projects in Chicago.

Chemical Alterations

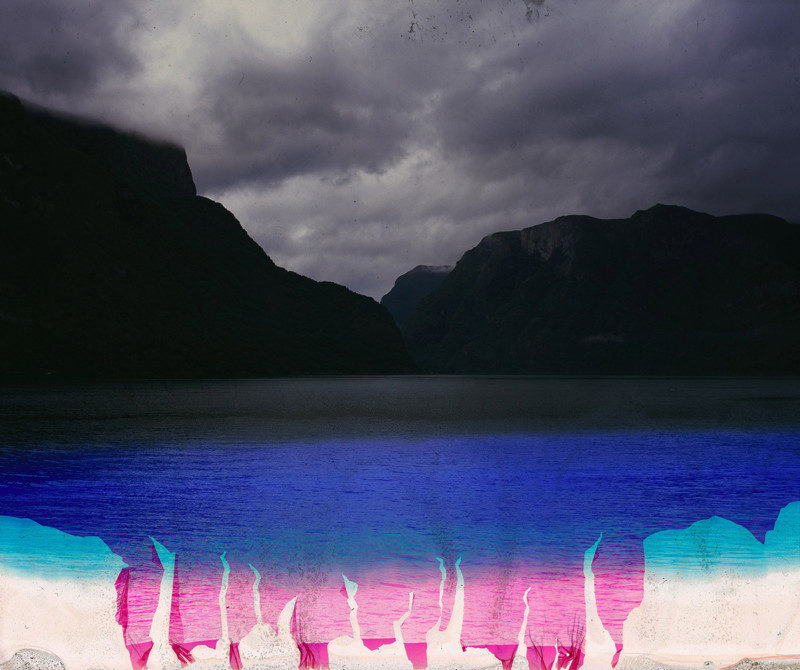

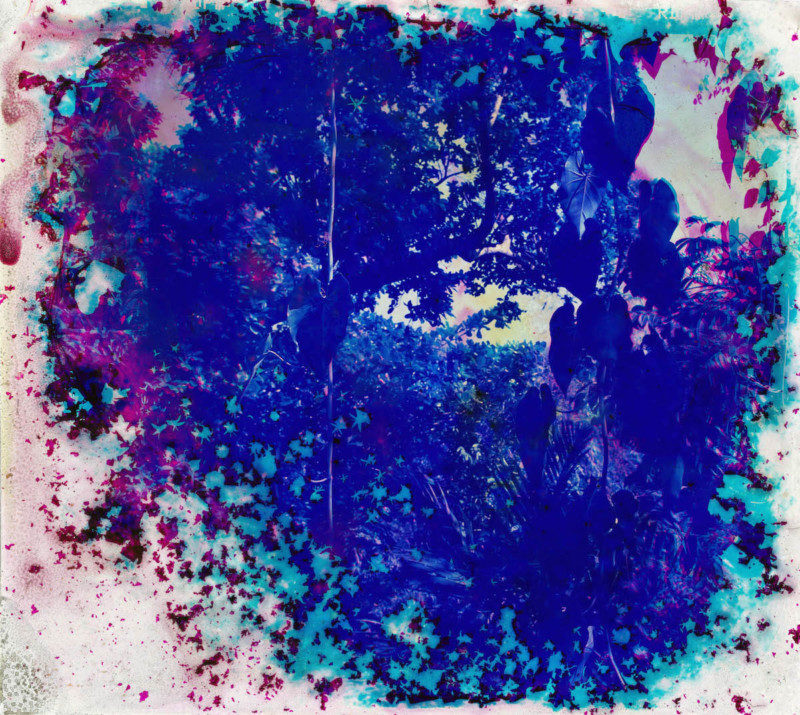

Chemical Alterations is both a series and process that engages with nature and the impacts of climate change. I photograph landscapes in biologically diverse regions and then use common industrial chemicals to alter the surface of the resulting imagery. This has the effect of draining colors from the dye coupler in the film and physically melts away each layer of emulsion down to the plastic base. In destruction new things are created–which we can see better once the film is drum scanned and enlarged. Salt crystals, bubbles, dust or other marks and patterns can get fixed into images during the process. There is a tension, as well as actual slippage, between representation and abstraction in the final imagery.

I photograph near my home-base and also seek out specific natural areas abroad. When out in the field I will often expose multiple frames (partially over each other along the film roll) which connect the changing scenes by allowing them to visually bleed through each other. Multiplication of time and space on the picture plane also leaves vertical bands of exposures and signals the inherent human-mechanical interaction.

My work is a way of coming to terms with ecocide. It is an action I can take to stimulate reflection upon and bear witness to our legacy in the current era of declining biodiversity.

Hey Doug, can you speak about your creative process from a technical point of view, and how it relates to a greater conversation about the environment?

My process for the Chemical Alterations work is done in two distinct places, one in the “field” and the other in the studio. Out in the landscape, I am making photographs on medium format film and often use a method of overlapping exposures to connect the frames/scenes in space and time. I try to get out into places that have different ecosystems from my home, which is gritty industrial Chicago. Once back in the studio with the film, I soak, spray, scratch, and generally destroy the full-color images using industrial and household chemicals. This has the effect of melting the layers of emulsion and dye couplers. When the destruction happens new things are created. My altered film is then drum scanned and printed for limited editions.

As a reflection of what humanity and globalization are doing to the earth, these images provide a sort of photographic illustration for ecocide. We too scrape, cut, soak, and abuse the planet as we deem fit to procure resources for survival, pleasure, or profit. Lately, I have been “melting” images of lakes and oceans below the horizon line so the water turns unnatural colors and dissolves where the emulsion crumbles away. To me, this can suggest things like pollution, sea level rise, water temperature increases, invasive species, and the hydrologic cycle. I’m using wet processes that are hard to control so the results vary and there is often a total loss of the original. New forms or details created by altering the physical surface of an image also reflect the tenacity of life, which should be a part of the conversation.

This is one way to come to terms with what I know is the defining issue of our lives. I have evolved into a dystopian pragmatist, meaning I have little faith in our collective ability to (willingly) enact helpful change on a scale that will matter. Not that we shouldn’t try. These images help me connect with the forces of change.

Was there an early occurrence or event that spurred you towards environmentalism? How did these feelings transition into a dedicated artistic practice?

Yes, I think there was something early worth mentioning. When I was three years old we moved from the city to a rural zone near a town called Libertyville, IL. I spent a lot of time outdoors there and felt a strong connection with the non-human life in the backyard, etc. About four years later we moved back to the city and then I subsequently lived in various urban, suburban, and rural areas. Interacting with nature while learning about the human degradation of the land, air, and sea bolstered my nagging feelings about the “elephant in the room” of Climate Change. Back then environmentalism was regarded as something left over from the hippy ‘60’s and not a looming apocalypse, it was not front page news.

My early work also focused on the human-nature balance. Perhaps this is due to living within the grid of a city, which provides a stark contrast with the organic-yet equally competitive-quality of more organic natural spaces. I found myself making photographs of the city through holes I scraped in pastoral prints of mid-western landscapes and making other tactile/sculptural photo-based works. It was important to touch the process rather than creating straightforward indexical tableaux, this feeling remains strong today.

When I see your images, I also contemplate the work of Anna Atkins and early nature photographers. How do you think contemporary photography has changed our perceptions of nature?

Anna Atkins was a serious scientist in the field of Botany and her photographic works (direct impressions of fauna specimens via cyanotype) were reference materials for continued study. The fact that they are historical aesthetic gems in the field of photography is secondary to her more pressing primary focus. That said, I have always loved her cyanotypes and feel a kinship with her because I also like to make direct impressions of objects including flora and fauna (as color photograms). There is a tactile aspect to the process of making impressions, where an object briefly touches the recording material, and the visual aspect signifies that time signature as memento mori (or the remembrance of death).

Contemporary photography is mostly useful to help highlight ironies of the human-nature balance in the current epoch. Seeing images of calving or melting glaciers as art, or well-composed aerial views of oil fields, quarries, highways, landfills… perhaps a burning forest or post-hurricane landscape, can document, highlight, or reveal important things. However, I would like to see more contemporary work that connects us with nature at purely elemental or base-level emotions.

I think your work is compassionate and altruistic towards nature, yet these feelings are explored through harmful chemicals. Can you speak about this juxtaposition and its redemptive quality?

One of the best parts of my process is the way that destructive measures yield generative results. They are very small, such as salt crystals forming or little pieces of dust and hair that get fused to the film when the chemicals dry. I love to zoom-in on a high-resolution scan of a tiny section of film and see the resilient grains still holding on to a scene from some far away landscape right next to the slippage of the emulsion in entropy. I get this “dust in the wind” Carl Sagan, “We are made of starstuff,” kind of feeling. What this suggests to me is that although we may be screwing up the planet today, ultimately, the longer game will be won by non-human life forms and the regeneration will continue. The more I bring the images toward oblivion the closer I get to some evidence of life as it currently is, does this make sense? We live in our own bath of chemicals and synthetics, pesticides and antibiotics, our reality is also in flux between representation and abstraction, I see this art as connected to that inquiry.

What sustainable practices have you adopted into your photography?

Well, photography is not the “cleanest” medium in that regard- especially when you need an analog physical object to work with. How I justify this is by comparing the action of making, and all the materials used to do so, with the output of something general such as a small apartment building or even a few minutes of the waste stream from some commonplace industry. In terms of scale the waste stream from art, including all photography, is tiny when compared with mainstream pollution. That said I reuse many things in my studio… I do fly to different landscapes and this is probably the largest carbon footprint of my practice.

We are amidst a turbulent political climate, and it’s frustrating to see the inherent lack of change or emphasis on environmental policies. How has this negligence impacted your art-making?

Not to be perverse, but it is fueling a part of my intention. The worsening ecological situation gives my work relevance beyond a commentary on the ephemeral nature of nature- it speaks to the frightening lack of values we humans have toward self-preservation and sustaining future generations. Part of the job of art is to help define a cultural identity. I see art making as an expression of the highest aspects of what it means to be human after one’s survival needs are met. That said I am certainly tired of the stories civilization or the media are telling us today and doing this is one way I have of telling new stories about our current disharmony with the nature sustaining us.

How does your photography practice give you hope for a more ecologically sustainable future?

It doesn’t. Sorry to end on this note but I have little faith in people to stop running on the treadmill of infinite growth models or technological fixes. I do have a conviction that if by some magic, our human world were to shut down then the earth would repair itself much faster than anyone might predict. This thought gives me some peace.

To see more of Doug’s work, please visit his website.