Zach Nader is an artist excavating new possibilities in content and aesthetics for existing photographic imagery through the use and misuse of contemporary image editing software. His reworkings of print ads, commercials and other disposable imagery has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including during a month-long nightly video installation on 23 advertisement billboards as part of Time Square Arts’ Midnight Moment. His work has also been previously shown at Culturrcentrum Hasselt, Belgium (currently); Centre Pompidou, Paris, France; Haus der elektronischen Künste, Basel, Switzerland; Eyebeam, New York, NY; Interstate Projects, Brooklyn, NY; and Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, Birmingham, AL, among others. His 3rd solo exhibition at Microscope Gallery “psychic pictures” opens in April 2019. Nader has been an Art & Science Residency at The Pioneer Works Center for Art and Innovation in Brooklyn, NY and has been a featured speaker at ICP-Bard, New York, NY, and Bard at Simon Rock, Great Barrington, MA, among others. Nader was born in Dallas, Texas and currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. He is represented by Microscope Gallery in New York.

Zach Nader

“psychic pictures”

April 5 – May 12, 2019

Opening Friday, April 5, 6-9pm

Microscope Gallery

1329 Willoughby Ave, 2B, Brooklyn NY

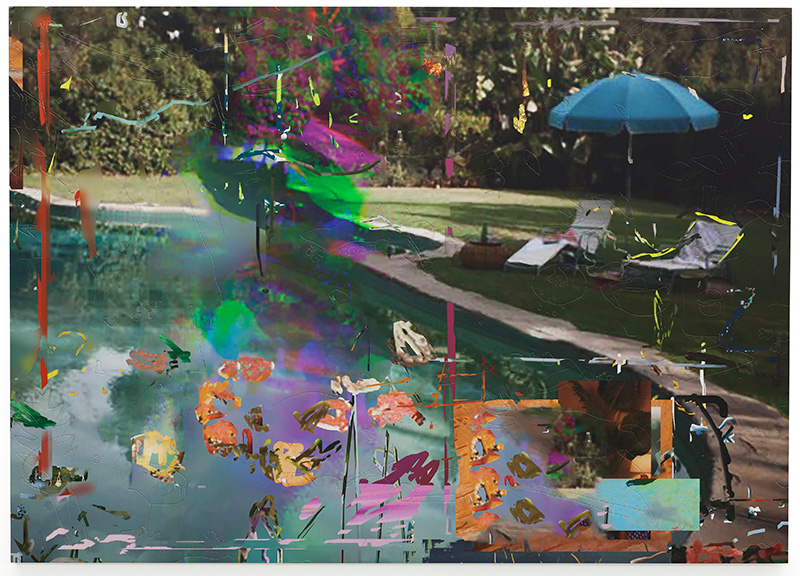

Zach Nader, “stay cool”, 2018, acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40 x 56 inches

Zach Nader, “stay cool”, 2018, acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40 x 56 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

Julia Wilson: Before we begin talking specifically about your work and exhibition, psychic pictures, I’m curious to know how you view/experience/interpret photography in the modern world – as someone who primarily works with/ creates images out of images-found-in-the-world. Usually, when I think about found imagery, I think about the postmodern aesthetic, which could be argued is no aesthetic at all, the rejection of authenticity, and a ‘jokes on you’ mentality. However, when I look at reproductions of your large-scale digital collages, I think about Cy Twombly’s Quattro Stagione even Boticelli’s La Primavera (forgive my grandiosity) but I see something almost-modern semi-representational renaissance-inspired complex imagery, and I find this unexpected combination of appropriation, earnestness, and awkward beauty insanely compelling. I’m curious to know how your relationship with your medium informs your work.

Zach Nader: I cannot imagine using any material other than photographic images as the base of my practice. When I think about humanity’s relationship to photography, I think about Gretchen Bender and Vilém Flusser. In different ways, and in the 1980s, they both pointed at a world programming, and programmed by images. This condition has only grown more palpable with time.

We see this everyday, with memes, advertising, news imagery, and images flowing across social networks. An easy example right now is TikTok, where images quickly spread influence, are remade or remixed, and generate countless versions that then infiltrate other platforms.

I am interested in breaking images open, running interference patterns, and assembling something new out of the parts. If we think of a photograph as projecting a potential future and every surface as a potential screen, an artwork can be an opportunity to see what sorts of stories might be generated.

While “beauty” is not something I explicitly seek, it is often an avenue into engaging with these pictures. A consequence of using advertising images with a high production value and subjecting them to these processes is that the end result does carry some of that shine all the way through. I look for ways to complicate my source material and format it into something new, including materiality and visualities. In the panel works, that means carving to embed images into the wood that engage with the printed marks I make with software.

JW: So we could say, based on my initial inquiry, that I am possibly reading into your images, based on my own background (Classical Greek/Roman studies) and projecting that into your work – which I guess you could say means its “working.” And I think aesthetic beauty creates that access point to create the want to dive deeper, whether or not it’s sought out or important to the work, as you see it. Proust wrote in so many words, that art is like turning light into heat. That is a bastard paraphrase, but I think about that a lot.

You mention above, Flusser, who has also informed much of my study of photography. And he asserts in A Philosophy of Photography, that because photography is reliant on a technological apparatus, its forms will always evolve with it. And so, as technology is rapidly evolving, so is photography – whether that is visually apparent or not in the image itself. So as someone who works with photography, as a medium, and not just for its depicted subject, and someone who chooses to highlight its technological and (maybe lack of) material context, would you argue that there is a unceasingly “photographic” quality in all images, whether its something on TikTok (forgive me I have just learned what this is from you) or a 1900’s Daguerreotype? Where does psychic pictures fall in its balance of medium and content?

ZN: The way I approach making work makes it difficult to wholly separate out medium from content. I usually seek to collapse boundaries (even if only briefly) and then attempt to build a new structure. I also feel that photographic imagery always has a material context – sometimes my panels, sometimes a phone screen, a piece of paper, a flash drive, a cell phone tower, undersea cables and on and on. For me, that context has a stickiness, it remains part of the content.

I do think that all images that enter the apparatus of the photographic transform and then follow the parameters of the apparatus moving forward. So, anything being imaged through a lens, being scanned, or being created or manipulated through software built out of the fundamental principles of photographic imaging is absorbed into that framework. Flusser understood this so early, that photography would eventually eat everything until there was nothing left outside of it.

In part, that is where my drawing in Photoshop originates. I went to school for photography and made what we can call straightforward pictures of things in the world for some time. Once I understood that a mark made at any point in the vast network of the creation and distribution of photographic imagery is on equal footing with the “primary” image, a whole new set of possibilities opened up. This quickly shifted into treating photographic information as material that could be painted or sculpted with.

Still from “psychic pictures” (2019) by Zach Nader, HD single-channel video, silent, 4 minutes 35 seconds. Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

Still from “psychic pictures” (2019) by Zach Nader, HD single-channel video, silent, 4 minutes 35 seconds. Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

JW: And now that we’ve more than covered “photography about photography,” I believe that there is much more here than that. Excuse the broad question, but where are you in these images? Where do the ideas/compositions originate inside you? Can you reference a specific piece?

ZN: Much like with medium and content, it can be difficult to delineate where I might begin or end in relationship to my work. I think of my practice as image-based experiments and many of my projects begin with me subjecting images I’ve collected to a series of conditions.

I think of the drawing I do in the work for this show as being semi-automatic, in that I am making a mark in conjunction with a scripted software action that folds some of that image material up and makes something out of it. For the compositions that are ultimately made, they build up in a similar way. I partner with myself on those though, making an image, keeping the parts I find relevant over time, and building over the rest. As that repeats, compositions begin to emerge out of my choices and from the lines of the source material. Pieces of the scaffolding, of the journey, remain visible throughout.

To talk about a specific piece, “hot dog holiday’ is a play on a summertime celebration. It is a collision of picnic tables, an American flag, cotton candy, hotel rooms and bottled waters. Chunks of figures, someone eating a hot dog and party banners emerge in the carvings. With all of the work in this show, I’m interested in these idealized spaces and objects as material that can be built up, that might bind to one another. Where the human figure might disappear or emerge, and what might adhere to it, is another primary concern. As we image and disperse ourselves across networks, how do we commingle with the other material whirling around? One thing I think about often is how we might relate to images we already know, how they shape us going forward, and ways to shift that story.

Zach Nader, “hot dog holiday”, 2019, acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40 x 56 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

Zach Nader, “hot dog holiday”, 2019, acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40 x 56 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

JW: I always think its interesting to map my intentions with my work, sit back, and then ultimately see what my work is telling me. More times than not, the work I’ve made from a place lesser known, works in more complex ways than the pieces I’ve hammered into position do – which often fall flat. I find this idea of semi-automation in a similar vein.

To get more concrete, I’d like to talk about the title of this series, psychic pictures? The world ‘psychic’ refers to the mind and soul, the immaterial, and things lying outside of scientific explanation. To my understanding, this seems in contestation with how we consider pictures – something evidentiary, “this happened.” How does this potentially oxymoronic pairing become your work?

ZN: I think of there being a distinction between images and pictures. Images flow across networks, are often subject to automation and can rapidly shift. They are material of which pictures can be made. Pictures are the printed photograph, the painting on the wall, and the image that has momentarily stuck to your screen. Pictures are fixed, however briefly, before spinning of into other variations. Pictures require being present, are encountered by humans, and have the ability to push on us as we push on them.

For psychic, I’m thinking both about the definition you give, and the idea of a person who claims to have the supernatural ability to somehow envision a future. This requires a type of presence too, a give and take. It involves knowing what the viewer desires or needs and pointing them toward a future they may have been unable to imagine.

So, the title is both about the generation of futures, and in turn the loss of other futures, pointing towards the preordained, and looking for ways to undo it. It is about maintaining the ability to dream of alternatives, to set a new course, while using uncertainty as a catalyst to move forward.

JW: Without giving away too much, can you tell me a little about the show itself?

ZN: The title of the show comes from the video, ‘psychic pictures’. It is a kaleidoscopic reimagining of colliding imagery; idyllic fragments of families at home and play spinning off into open ended stories. Additionally, like hot dog holiday, there are more wooden panels that I hand-carve and then print over. I also have other works in which I have printed on outlet covers, smashed aluminum cans and a clock, as well as a few new sculptures I hope everyone can come see in person.

Zach Nader, “outlet #4”, 2019, UV print on steel outlet wall plate, 5 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

‘psychic pictures’ runs from April 5 through May 12, with an opening reception on Friday April 5 from 6-9pm. For additional information please contact the gallery at inquiries@microscopegallery.com

To view more of Zach Nader’s work please visit his website.

For more info on the exhibition, please visit Microscope Gallery’s website.