Shoshannah White is an interdisciplinary artist based in Portland, Maine, though currently spending the year in Roswell, New Mexico. Shoshannah’s practice includes photography, painting, sculpture and public art installation. Her work has been exhibited at institutions including George Eastman House, The Center for Maine Contemporary Art, The Maine Jewish Museum, The Tides Institute Museum of Art. Hew work is included in public and private collections including WM Hunt’s Dancing Bear Collection, Bates College Museum of Art, the Glickman-Lauder Collection at the Portland Museum of Art and at Dickinson College. Her public work is sited throughout Maine and her private commissions are installed across the United States. She has received grants and awards including the Berkshire Taconic Fund, The Kindling Fund through Space Gallery a re-granting program of The Andy Warhol Foundation and through the Maine Arts Commission, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. She has been selected for artist residencies in the United States, the Canadian Maritimes and in Norway, within The Arctic Circle. White has been a guest critic, visiting artist, juror and has taught workshops in a number of specialized photographic and painting techniques. Shoshannah received her BFA from the Savannah College of Art and Design. Her work is represented by Corey Daniels Gallery in Maine, Pilar Graves in Los Angeles, California and Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto.

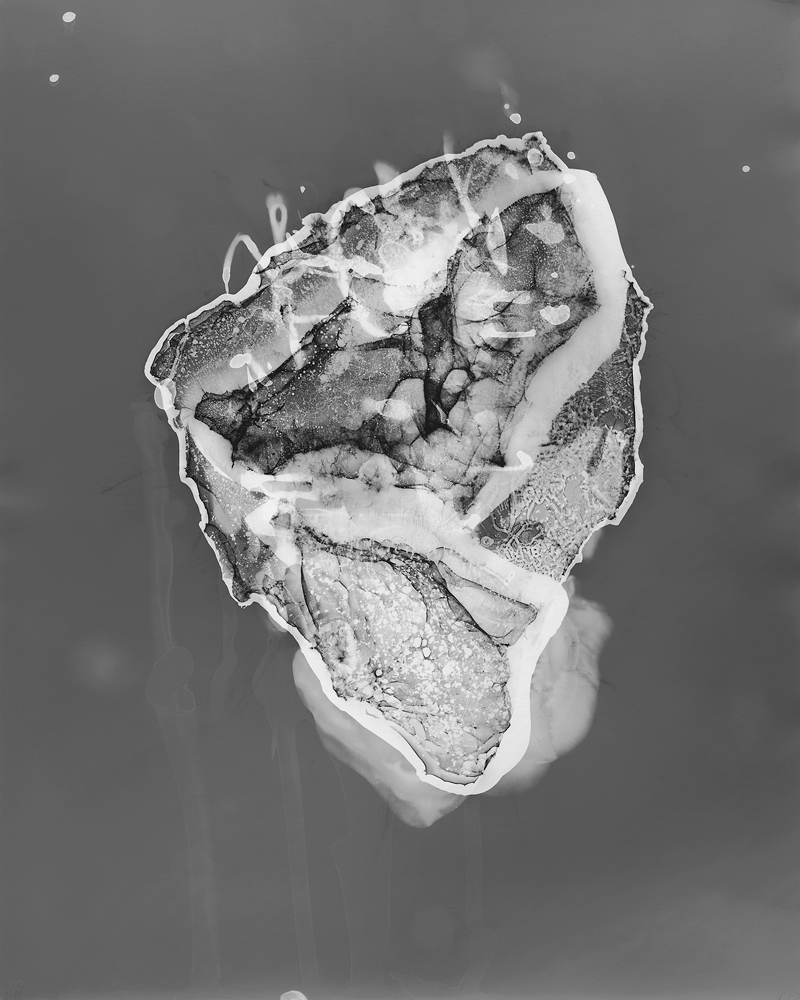

Svalbard Iceberg #12, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

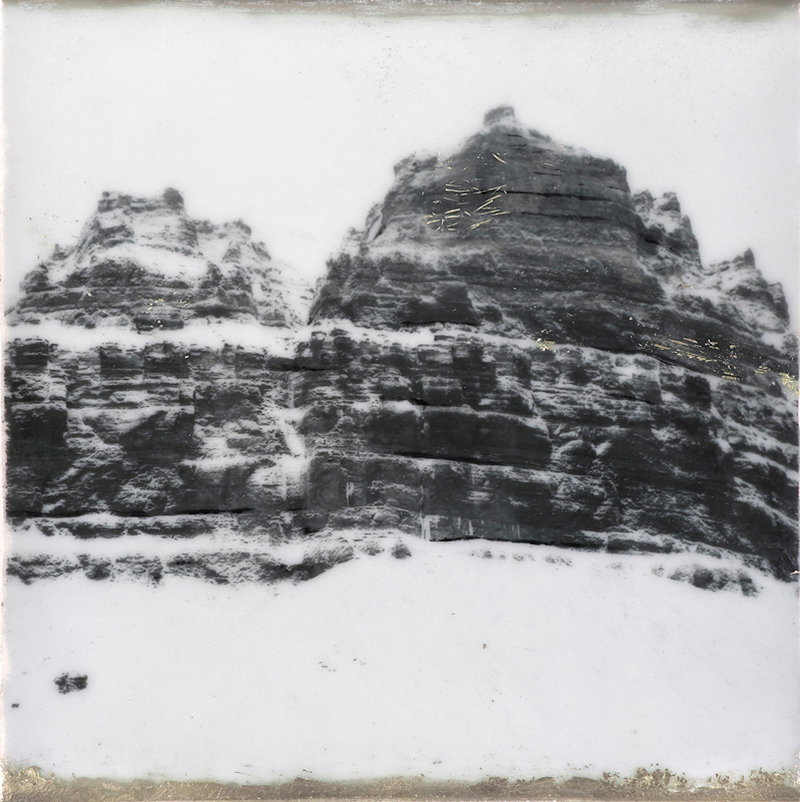

Magdalenafjord, Graveneset Glacier, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

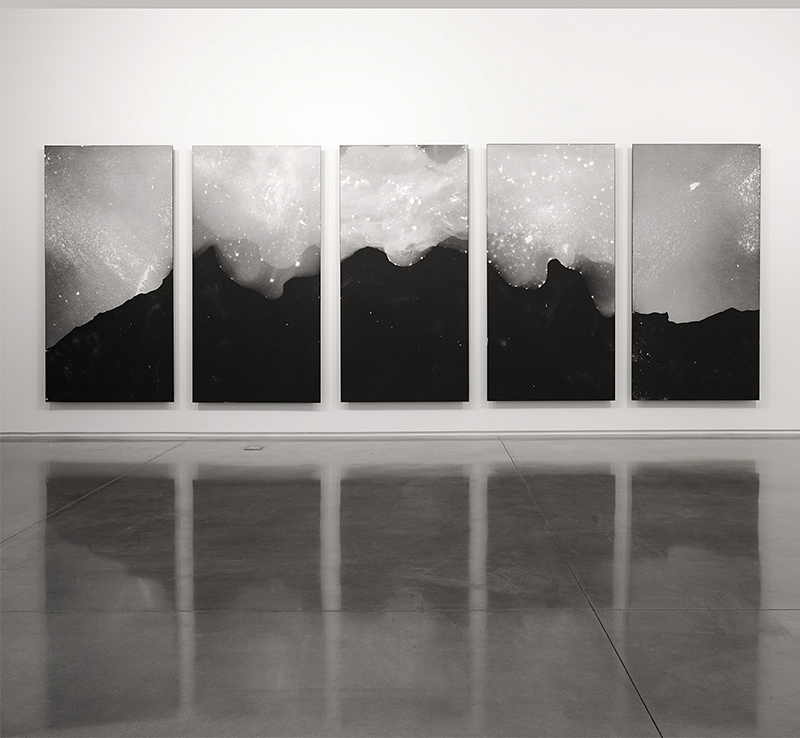

Strata and Temporary Ground

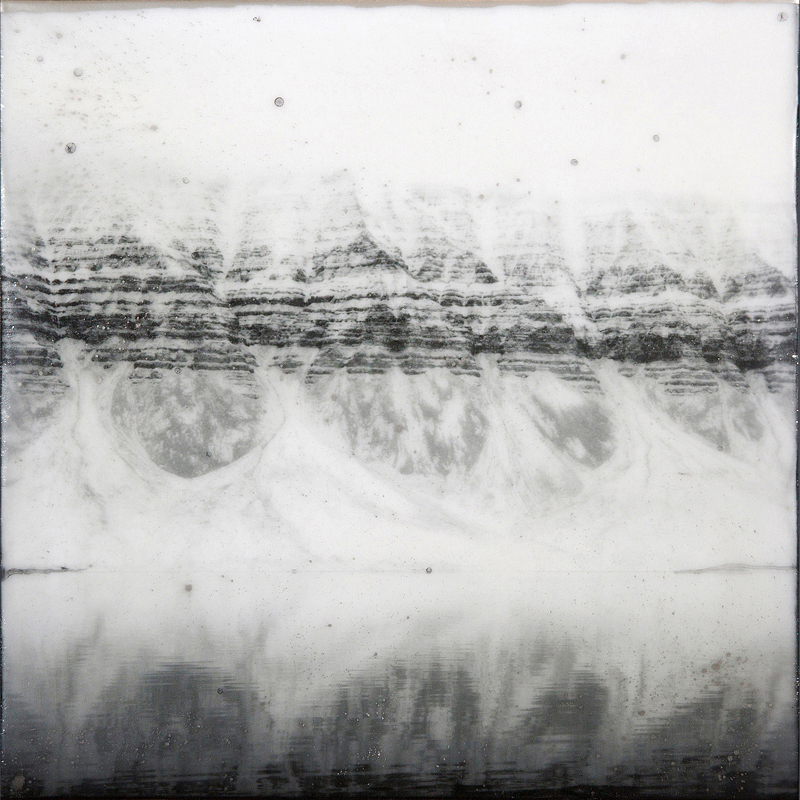

Temporary Ground and Strata are two parts of a project contrasting glacier ice and raw, unprocessed coal: materials formed through compression over time, both with planetary history locked into their dense and layered makeup. Each series pairs Arctic landscape photographs with (cameraless) photogram prints made directly from raw material collected in specific environments to consider both real and fabricated landscape:

TEMPORARY GROUND includes color photographs of Arctic glaciers and underwater icebergs as well as photogram prints of melting glacier ice. Black and white photogram prints were made in Alaska in a temporary darkroom and photographs were captured within the Arctic Circle.

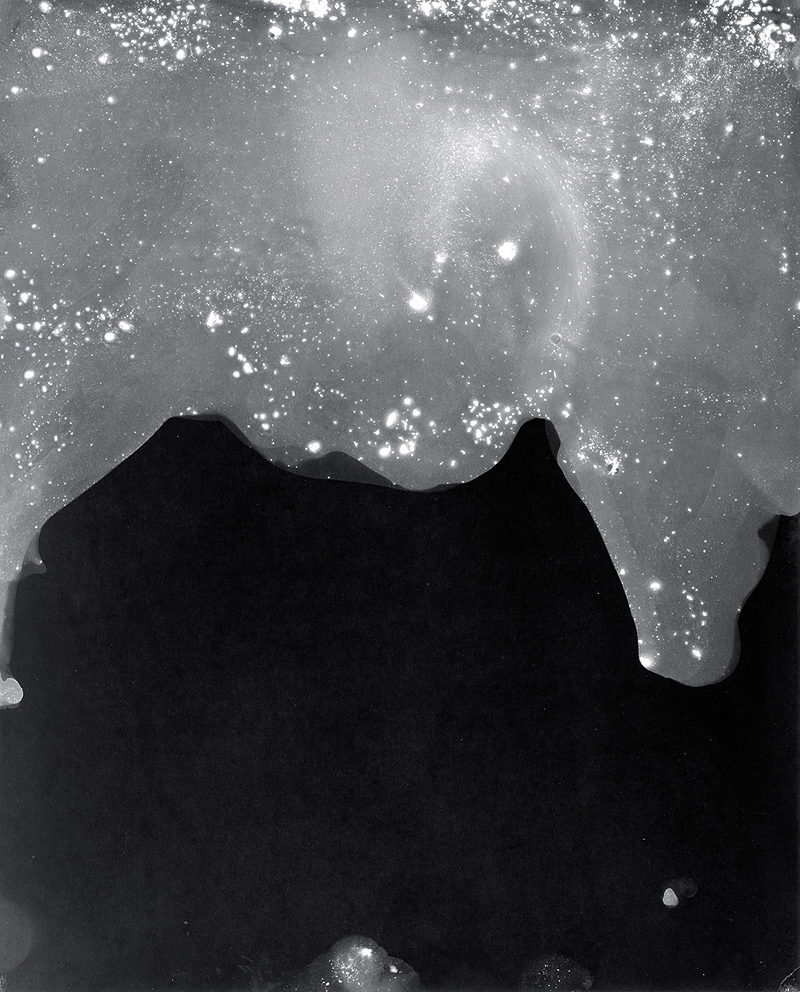

STRATA pairs Arctic mountain landscape photographs with photogram prints made from a slurry of coal dust and melted glacier ice. The photographs were made in Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago within the Arctic Circle with a history of coal mining. Coal was collected from active and inactive coal mines in Pennsylvania.

While the content relates to the environment, the work is very much about our psychological connection/disconnection with the world around us. As a photographer working in multiple media and across disciplines, these images exist in many forms from original framed prints and mixed-media works to multi-part installations as well as an ongoing exterior mural project: CHATTERMARK.

Sveabreen Glacier, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

Svalbard Iceberg #27, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

Temporary Ground, Contact Sheet

Kyra Schmidt: Shoshannah, thank you so much for your time on this. Let us jump right into some questions with regards to your artist statement above:

You’re working in the genre of landscape, yet your images stand apart from the proliferated aesthetics. You are working with photograms, and photographs that appear to be worn or hazy. Can you talk a little about how environmental issues inspire process and aesthetics within your work?

Shoshannah White: Sure, while the subject matter is inspired by science, climate and/or nature, the work is really grounded in aesthetics and a kind of fascination with unseen worlds – whether that is a psychological world found between people, or a physical world like underground root systems or hidden information within glacier ice. Either way, the work is a connector to help me get closer to what’s happening on the planet and an access point to understanding human connection or concerns of the environment more deeply.

My current series considers the Arctic. In one sense I’m making somewhat romantic landscape images, in another I’m photographing a changing and hugely vulnerable environment. At the same time I’m working with raw materials from specific landscapes: in this case, glacier ice and raw unprocessed coal. In pairing landscape photographs with photogram prints, I’m thinking about both real and imagined landscapes. I’m also thinking about the environmental relationship between these two raw materials in that coal fueled the industrial revolution, the results of which are now impacting a major climate event. Further still, I’m interested in the geologic parallels between these two materials: both are formed through a layered compression over time and both hold planetary history – of course in very different ways.

Also, content and materiality play equal roles in the work which are layered into the physical work as well. For example, if I’m working with an Arctic landscape I might cover it with an emulsion of wax to mimic the snow and sensibility of the environment and incorporate metallic bits which appear and disappear depending on where you’re standing or what angle light is hitting the surface. The translucent medium allows light to travel through the material, which physically and metaphorically separates the viewer from the landscape and the scattered metallic spots reference the dirt and industrial particulate which is currently landing on the ice and snow, darkening the surface and speeding up melt due to increased heat absorption.

KS: Your process is wonderful. In a sense, you are making physical sensations of experience with disparate materials. The beauty (or tragedy?) of it is that such experiences with and within the land aren’t necessarily quantifiable. Do you ever find yourself frustrated with the disconnection between photography and real, lived moment?

SW: Thank you, I love that description. If I understand your question, I think the answer is really both yes and no. With my work being so process-oriented I often find myself in a landscape, making photographs of what seems to be a pristine moment. Of course there is no pristine environment on earth today and so I’m capturing the beauty of a highly compromised circumstance. I work a lot with the idea hidden or obscured information. Spending time in the Arctic began with an impulse to be in a part of the world so impacted by humans but with very little visual evidence. At some point, it became clear to me that I had to augment the implication of a pristine landscape with something empirical, data-based and tactile. This is when I started making the cameraless prints. It’s important for me to make direct contact with the landscape, physically handle the raw materials and capture that connection through touch and direct exposure to photographic materials. Taken together, I’m able to appreciate the grandeur while also connecting with the components that make up the landscape. So, really, I’m grateful that the medium of photography gives me an access point to be in the moment and experience these very special places while considering our collective impact and future outcomes.

Barry Glacier Ice #5, Gelatin silver photogram

Beloit Glacier Ice, Gelatin silver photogram

KS: In your artist statement, you mention this idea of a connection/disconnection between (us) and our world. As I imagine many artists struggle with the gaps between experience, sensation, information, meaning and reception, I must ask: What would be the character of this relationship for you? Is it distressing?

SW: Do I find it distressing – well again the answer is both yes and no. I’m trying to describe this space that we’re all part of and also distinct from.

The sense of connection/disconnection is a repeating theme in my work. Through both content and materiality I’m interested in this space between us and our experience of the world – whether that be psychological, theoretical or even physical. We’re connected and also disconnected digitally, emotionally, physically and I’m not sure how to navigate it. We are pretty stratified as a culture yet layered and complex. With my work I’m trying to get closer to the questions, to people, specific environments, geologic events. I’m interested in this idea that although things are constantly changing, there’s a kind of basic code of nature/life that is constant and repeating and I try to reflect that in content and form.

The relationship for me is broad. In a portrait I might be describing the space between people in that we can communicate through language: words or otherwise, but we will never know exactly what someone else is experiencing. Still we’re drawn or repelled magnetically to and from one another as separate entities.

In my current Arctic series, most of us know the ice-cap is melting and sea levels are rising but it’s removed from our daily experience. Anchored next to a melting glacier, it’s impossible to ignore the sound of the ice breaking, the swell caused by giant pieces falling into the water and watch the broken bits float out to sea. It’s not cool to talk about emotion and art, but for me, I need to be moved in order to make work. Working directly in specific landscapes, I can slow down and have an experience. Whether that’s tangible and data-driven like in the case of a photogram made from glacier ice, or abstract in the sense of photographs that might capture a particular sensibility or resonance of the environment.

Blackstone Glacier Ice, Six gelatin silver photogram prints

Coal Landscape, Five Panel Mural Installation

Strata, Contact Sheet

Coraholmen, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

Longyearbyen, Coal Mountain, Photograph with wax, oil paint, metallics

KS: It seems to me that there is a movement of contemporary photographers (let’s stick to the landscape genre for now) adopting a hands-on approach to image-making whether it be via cameraless imagery, stitching, cutting, etc. Perhaps it’s a liberal, anti-modernist approach to representation. Why it is important for you to work in this manner?

SW: Yes, there’s a wonderful resurgence of hand-made and cameraless photographs – many employing historical processes and techniques. I think, possibly with so much of our lives being lived digitally, there’s an impulse to work physically. For me, I grew up in a family filled with artists and psychotherapists and so I had early training in understanding the world both visually and conceptually. It was also a critical time in the environmental movement and this too is threaded into my psyche – all of which shows up in my work today. I have early childhood memories of being in the darkroom, watching an image emerge from a blank piece of paper under that hypnotic, red light. So, there’s a sense of play and discovery that goes along with analog photography which feels like part of my DNA.

There’s an energy connected with handling materials in addition to looking at them. I’m a physical learner and so I follow my curiosity, showing up in specific environments and making work in direct contact with the raw materials of the landscape. The melting of the ice onto the paper left its mark, made a physical impression, or the coal scratches the emulsion, stains the paper. Learning how qualities of the ice or coal rendered photographically was a discovery process for me. The initial curiosity acts as an opening to an embedded narrative in and around the material – helping to familiarize myself with the environment itself and also underlying issues related to place. This is all mixed up with that crazy magic of light, chemistry and materiality of working in a darkroom.

KS: With your own artwork, and with your public project CHATTERMARK, you are less interested in a didactic, political agenda and more interested in a relationship grounded in care, attention, and appreciation a spiritual tie to the land. For me, your artwork opens-up a world where one can lose themselves ⎼ a space where the mind and eye can travel elsewhere. And yet they are potent environmental statements. In what ways do you see contemporary artists can facilitate social or environmental change?

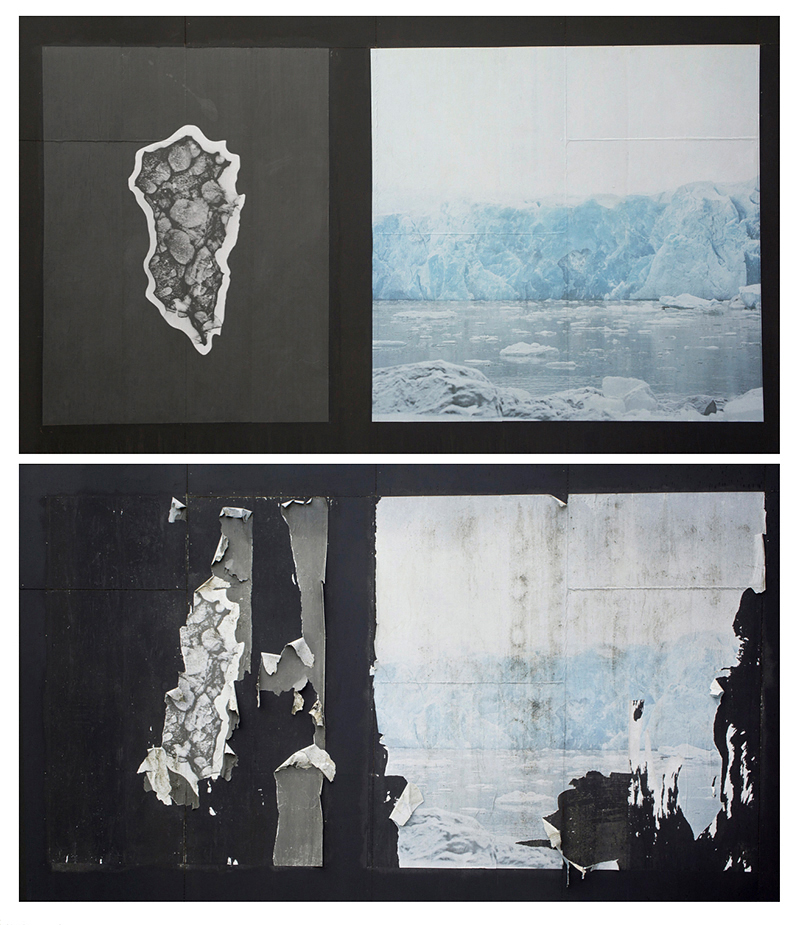

SW: Thank you, that’s a wonderful description and also I love that the work has been transportive for you. To briefly explain the project, CHATTERMARK, it’s a mural initiative bringing images of the Arctic and melting glacier ice to the streets. Images are printed at mural scale, adhered to public, exterior walls and deteriorate with time and weather. Each installation points to a digital platform featuring varying perspectives on the environment. The website is a landing site and portal to work by fellow artists as well as scientists, musicians, psychotherapists, etc.

For me, it’s important this project is less informative and more poetic. There are so many ways to enter a dialogue about the climate. The issues themselves are completely overwhelming and everyone is coping in their own way. I can’t speak for other artists but for me, this work is an entry point to try and better understand the components of a larger conversation. By sharing my work and the work of others on the website, it’s a way to start a dialogue and begin to sift through what’s happening. For me, I enter through sensibility or by tying into something I can relate to on a deeper level. It’s only at that point I can begin exploring and asking questions. With this project I’m inviting people into that process. I don’t have any grand notions that the work is changing the world but my hope is that some wisp of connection can ripple out a bit. We all know there is imminent danger of rising temperatures and sea levels, and also, we can’t keep that top of mind all the time. By unexpectedly coming across an image of a glacier on the way to work or to a meeting, it gently brings the idea of the natural environment back into the rush of the everyday – with imagery of the natural world experienced out of context and within the in-between moments. Artists come to the conversation through a channel which activates different pressure points than statistics or data. I think both are hugely important and exist in very different ways in our consciousness.

Astral #9, Coal and Glacier Water, Gelatin silver photogram

Landscape Single, Coal and Glacier Water, Gelatin silver photogram

Wormhole, Coal and Glacier Water, Cliche verre

KS: Very well stated. Working with social or politically charged imagery can be tricky, but I think it is the little ripples of affect that we have to hope for. Can you tell us what you are working on now? Or what is up next for you this year?

SW: I’m currently very lucky to be spending a year in New Mexico away from my beloved home state of Maine. I’m learning about the desert, mining and a whole new set of raw materials and new work is developing. I’m also working on a book project to include both the glacier ice and coal work. And finally, I’m continuing work on CHATTERMARK.

Forecast Exhibition, Hanging Diptych Mural Installation

Shoshannah installing a piece for her project CHATTERMARK

from the project CHATTERMARK

CHATTERMARK public installation, 9 months apart

To view more of Shoshannah White’s work please visit her website.