Jennifer Bacon was born in Bellevue, Washington in 1987. She received a BFA in Photography from Seattle University in 2017 after transferring from Bellevue College. She currently lives and works in Portland, Oregon as a recent MFA graduate from theVisual Studies program at PNCA. Her exhibitions include, DARKROOM IN USE, a solo show featuring new works that explored the boundaries of the traditional black and white darkroom. Her work has also been exhibited internationally at PH21 Gallery in Budapest, Hungary, with many other selected group exhibitions across the United States, most recently at Lightbox Photographic Gallery in Astoria, OR, Washington State University’s Fine Art Gallery 2 in Pullman, WA, Photographic Center Northwest and Gift Shop Gallery in Seattle, WA, and Blue Sky Gallery, Verum Ultimum Gallery, and the Center for Contemporary Art & Culture in Portland, Oregon, among others. Jennifer is the current artist-in-residence at Leland Iron Works in Oregon City, OR as their featured Emerging Artist of 2019.

Process-based, Ongoing

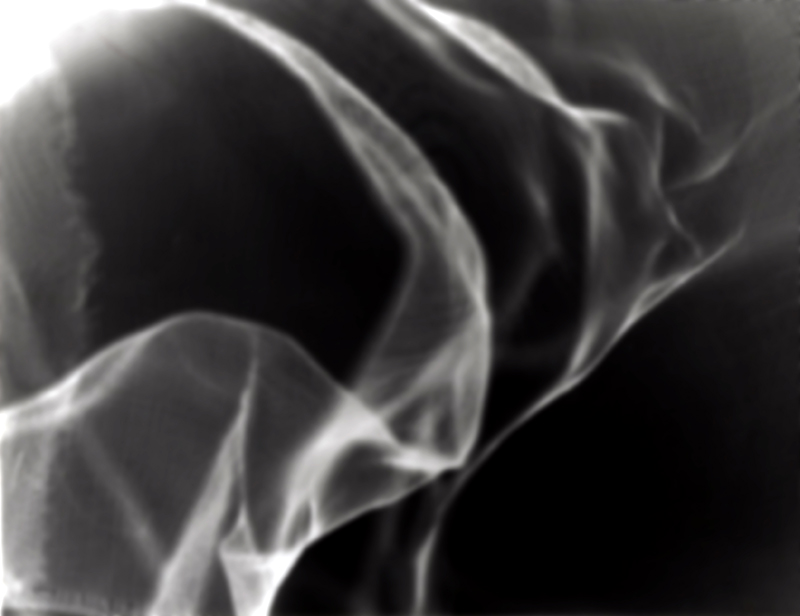

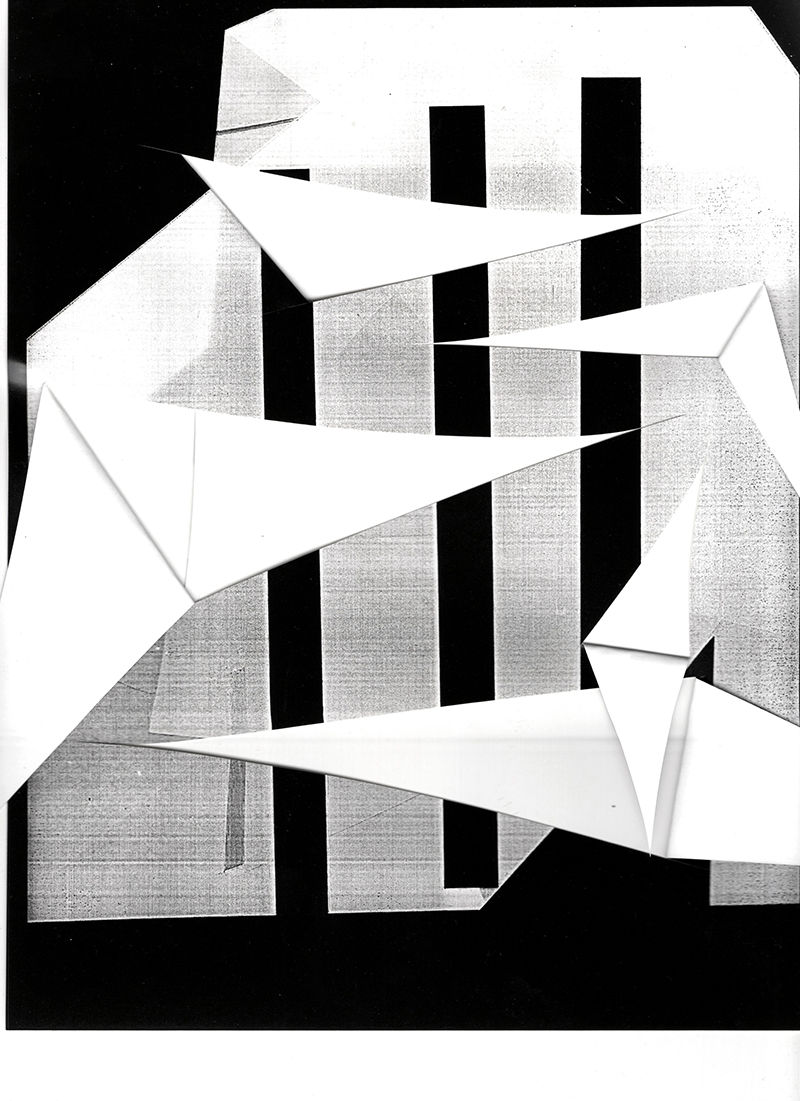

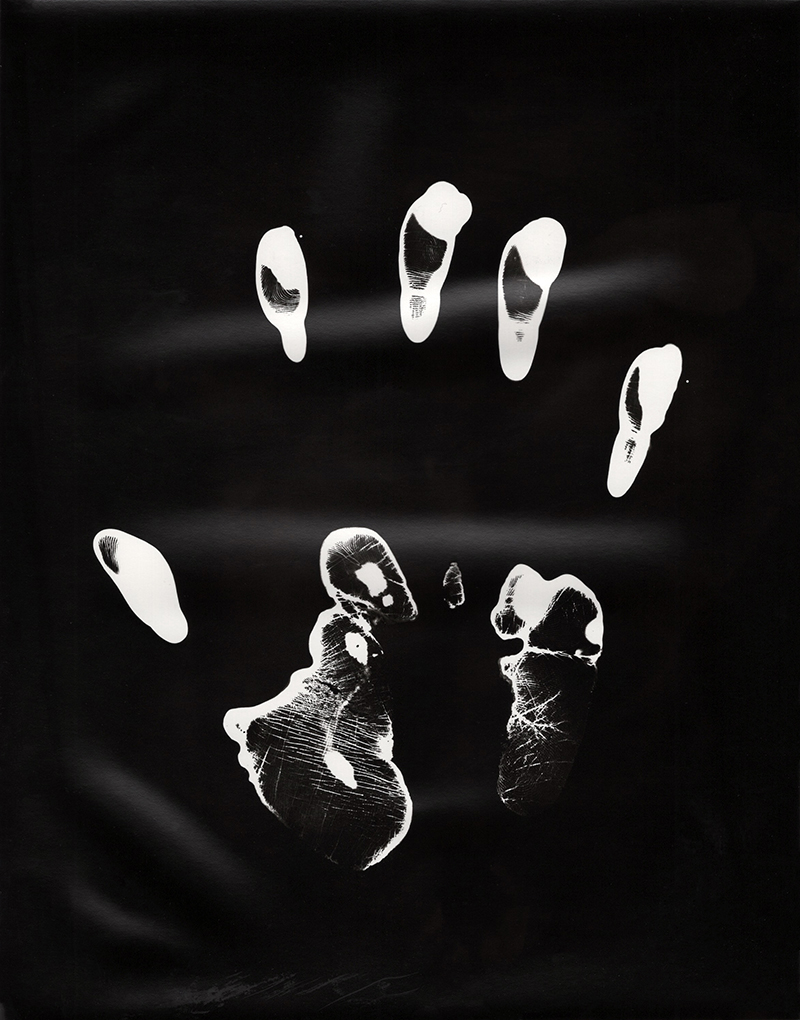

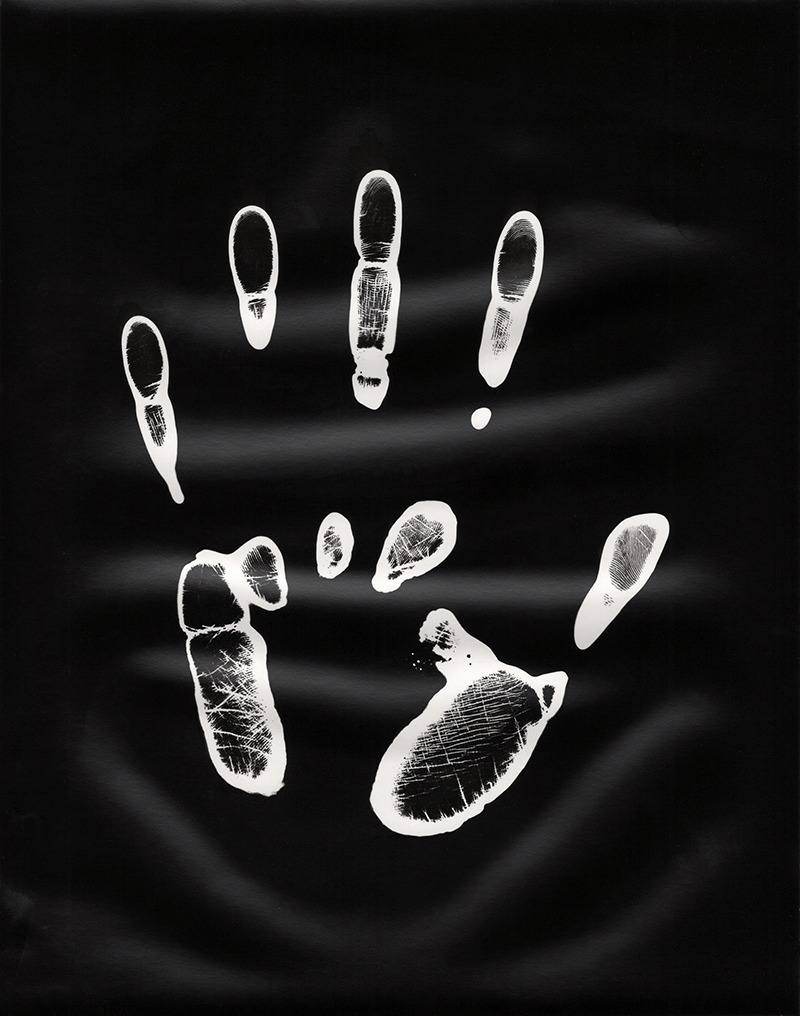

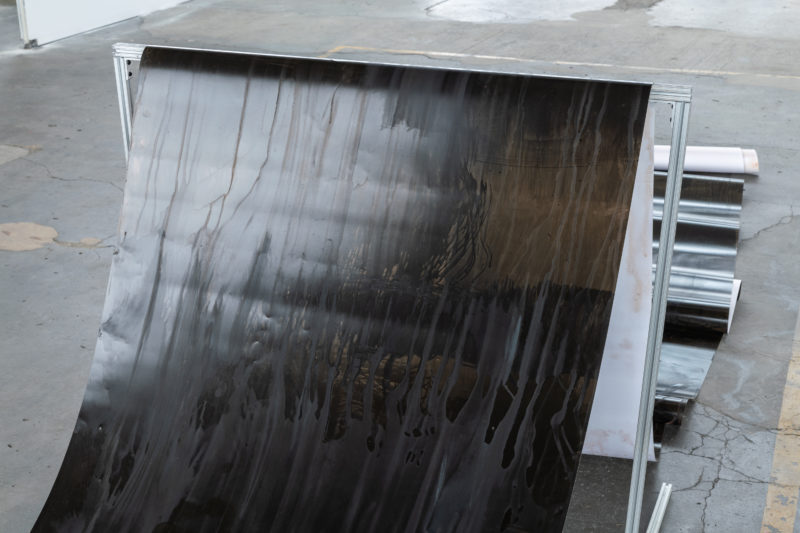

This body of work references the history of the photograph. By utilizing black and white, light-sensitive photographic paper outside of its traditional use in the darkroom, it attempts to subvert and break from the traditional conventions of photography. I have found, akin to several contemporary artists, that the darkroom can be limiting and restrictive for an experimental process. While I have a deep passion to the craftsmanship of black and white photography, this work strives to reveal the possibilities of light sensitive materials in a way that engages wonder, imagination, and phenomena. In the making of this body of work, there were no cameras used, sometimes not even standard processing chemicals; these photographs are photographs of photography. My thought process while making this series of work encourages the viewer to question the absolute essence of what it means to be photographic.

Kyra Schmidt: Your work is about photography itself, its ontic status as an aesthetic and cultural object. As a fellow proponent of photography’s multiple forms I am curious, what this visual narrative (or lack of) offers you?

Jennifer Bacon: For me, it presents the viewer with an opening to reconsider what they have personally deemed photographic. I like to hold up an imaginary 5×7 inch print in my thumb and index finger and ask: “What do you see in this photograph?” It transforms into a magical thing. Each person creates the image in their mind; they see their perceived idea of what a photograph is, what it is made of, what it depicts. When I imagine a photograph as a 5×7 inch print, I see a gloss-surface of my friends and me in grade school, faces overexposed from flash and slightly out of focus. The photograph is about memory, the illusion of perception, and it starts at the base of its materiality as a medium.

By working in the ways that I do, the viewer gets to decide whether this image/object is a photograph or not. I simply bring forth the photograph at its most basic, fundamental level—radiating in its self-referential and material potentialities—opening up the medium to encourage a shift from the traditional consideration of the photographic. I feel that this type of narrative, under the giant umbrella of Photography, allows for multiple interpretations of method and meaning. I find this facet of photography to be very liberating for and in an experimental process.

KS: While connected by the celebration of the experimental process, the visuals you present in this processed-based work are disparate. What is the benefit of working outside the tradition/restrictions of a define series?

JB: Right. This series follows a common thread with only their visual qualities being tangential. At the base of every photo-experiment I start with a “what will this look like?” My process is whole-heartedly fueled by wonder and curiosity. And here, the benefit of working outside a restrictive definitive series is that I am able to introduce many avenues of media, inspirations, and technologies. For example, in the pieces that I call “flatbed photograms,” I’m working with materials that could be used to make traditional photograms in the darkroom (e.g., transparent shipping material and light-sensitive paper scraps), but with the flatbed scanner the process is expedited and easier to share via social media and other digital platforms while also allowing illusionist qualities like depth, shadow, and unexpected highlights to be generated by way of the anatomy of the scanner itself.

KS: Certainly, this way of working—experimentation via wonder and curiosity – enables an open space for each work to take shape. Charlotte Cotton, in Photography is Magic, relates this type of sleight-of-hand—the wonder you speak about in your statement – to close-up magic. To quote her directly:

“Photographic magic opens us to multiple possible meanings of our visual world, and calls upon our collective ways of looking at it; it also offers us ideas of what that visual world might imply about our contemporary condition.”

Do you see a way in which the polysemous image might lend itself to a discussion of culture, society, or politics?

JB: That is an interesting question, certainly I could allow for the series to comment on our contemporary condition that’s been discussed by artists and photographers alike; that of the overwhelming nature of the digital image and its constant encroachment on our everyday lives. I do feel that my work allows for a refresh button, if you will, on the nature of what photography was about from its inception—the science, the wonder, the phenomena of it. Historically, the “proto-photographers” of the late 18th century and into the 19th century were on a quest to expand and enrich photographic possibilities. In a way, I follow this same path of inquiry and discovery while maintaining a practice that is aware of the digital image onslaught, and then engaging in the technological potential that accompanies that.

KS: Your experimentation process is reminiscent of photography’s early practitioners yet in an expanded practice as George Baker has named it. I can recall reading texts about William Henry Fox Talbot referring to the contact print as a writing of light by Nature herself—a beautiful degree of wonder that (maybe) still hangs on to contemporary photographic discourse despite its ubiquity. I feel as if we (photography) are in an in-between state right now, a sort of “catch-all”. I am curious, do you see issues with the way in which contemporary photography is viewed today?

JB: I have a hard time with photography, really. I do feel as if I am in an in-between state within the medium itself, yes. The camera as a visual tool became easier for me to understand after reading Vilem Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography, specifically where he introduces the “apparatus as the seeing machine” born from the Industrial Revolution: “The photographic apparatus lies in wait for photography… Their [the apparatus] intention is not to change the world but to change the meaning of the world.

I mention this because there are no cameras used in this series or in my other recent works. I work with traditional balck and white silver gelatin papers and extend their potential by using flatbed or handheld scanners (which also create ‘camera-less’ images similar to the base idea of the photogram). I think you, Kyra, understand this fissure in the medium, the traditional materials used in non-traditional ways and the complete exclusion of a camera. It feels like the aesthetic of the work is aligned with the “common” view of photography today but it’s not.. Not without the initial acknowledgement of the apparatus’ absence.

It is both this omnipresence of photographic technologies, and lack thereof, that complicates the ways in which contemporary photography is viewed today. I spent a lot of my time in graduate school making cameraless photographs that were didactic, even cynical sometimes. I gradually became more and more frustrated in this pedagogical approach to reach the viewer that I finally (with the help of mentors) let go of this need I felt I owed to the medium and to my audience. This brings me back to ideas mentioned before: the material is presented a deceptively elementary state as a way for the viewer to make of it as they will. Yes, the magic of the medium!

KS: Literarily, philosophically, and visually, what/who inspires your work?

JB: Honestly, my work is fueled by frustration. This is a frustration I feel with a seemingly exponential passion… similar to the passion I feel for the medium of photography. As a budding photographer, I demanded the best of my darkroom printing skills and knowledge by way of utilizing traditional techniques with a modernist approach to process. But to what end? What is a Photographer? What is a Photograph? The more I searched for the answers to these questions and those similar (like many artists and photographers) the more I was driven to go beyond the boundaries of photography, beyond the perforated edges of photo-sensitive paper, beyond the limitations of traditional and digital photography.

Later on in my arts education I was introduced to a questionably ironic poet in The Hatred of Poetry. Ben Lerner presented poetry in a way that I was able to insert Photograph into Poem and Photography into Poetry. This book offered a pivotal transition point for me and my work that really enabled me to let go of the restrictive limitations of traditional procedures in pictorial practices that I had been striving to obtain. Rather than making meaning, contriving a narrative with representational photographs, I started to think about them ontologically, fundamentally. Fueled by research starting with Concrete Photography by Gottfriend Jäger, I began making photographs that were inspired by the photograph itself, photographs of photography, based solely in materiality and process.

KS: Yes, I am in fact familiar with Gottfriend Jager’s text! And of course, I share this same frustration with you. In a world where everyone is or can be a photographer, what distinguishes the Art? This is sort of a rhetorical question.. I certainly don’t have an answer for it! What is a photograph anymore amongst the creolization of contemporary art practice? Where is the line drawn or do we even need one?

JB: No line needed, be free! That is what an experimental process is all about, in any medium.

KS: Well stated. Still.. I am wondering.. what do you hope to find for yourself and your work beyond this invisible boundary of photography? Within your art practice, what would you say you are searching for—aesthetically, philosophically, or even phenomenologically?

JB: The boundary of photography is such a weird thing, an idea first introduced to me through the work of Alison Rossiter. Her work lingering on this boundary between photography and painting—The New York Times claimed that the way in which she dips and pours developer onto expired, found photo-sensitive papers is akin to the way painters stain canvas creating abstract compositions. At the time I became completely infatuated with Rossiter’s work; the process, the simplicity of it, and the quick, commendable, and wide-spread recognition. I thought to myself, It’s too easy. Overtime coming to understand that it’s not only about Rossiter as a photographer but more about the process and the paper (material) itself—the exposure of the break down of its chemical properties, the torrent of time, the maximization of material…

That being said, I would say that I am searching for a glow, an embossed glow, on the edge of this weird membraned bubble I imagine as Photography. The edges are where the materials are most pressured, where I think is the most possibility for uncovering “new” potentialities. It’s exciting! It excites me to think of all the possible avenues of experimentation that are yet to be pressured out of that invisible boundary within photography and Art as a whole. Plainly, with my art practice I am searching for overlooked simplicities of the medium.

KS: Jen, this has been such an enlightening conversation! You have given me so much to think about. To wrap things up before we wind too deep into this tangent.. What is in store for you right now. What is up next for you and/or work?

JB: Thank you for this opportunity to reflect on and discuss my work and photography at large. It is truly a humbling experience to share my time with you and those who may read this. Now? Freshly on the other side of graduate school? I am participating in an artist talk and exhibition at Pacific Northwest College of Art’s new Glass Building this winter to conclude my time as Emerging Artist of Leland Iron Works Residency of Oregon City, OR. For now though, I will continue a studio practice, submitting content to shows and residencies across the country, and continue to share ideas with you and others on social media platforms like Instagram:

(@jenrbacon). Thank you again!

Image by Mario Gallucci (@mariogalluccistudio)

Image by Mario Gallucci (@mariogalluccistudio)

To view more of Jen Bacon’s work please visit her website.