Christopher E. Manning has an MFA from SUNY New Paltz and BFA from Manhattanville College. He is currently the Exhibitions Manager at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, as well as a Professor of Visual Art at Manhattanville College. His work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally, being featured in the New York Times, Queens Chronicle, Aint–Bad Magazine, Polaroid Originals Magazine, Photoklassik International, amongst other publications.

His first monograph, Everything, As Perfect As It Seems, is now available for pre-order from Aint-Bad.

Everything, As Perfect As It Seems

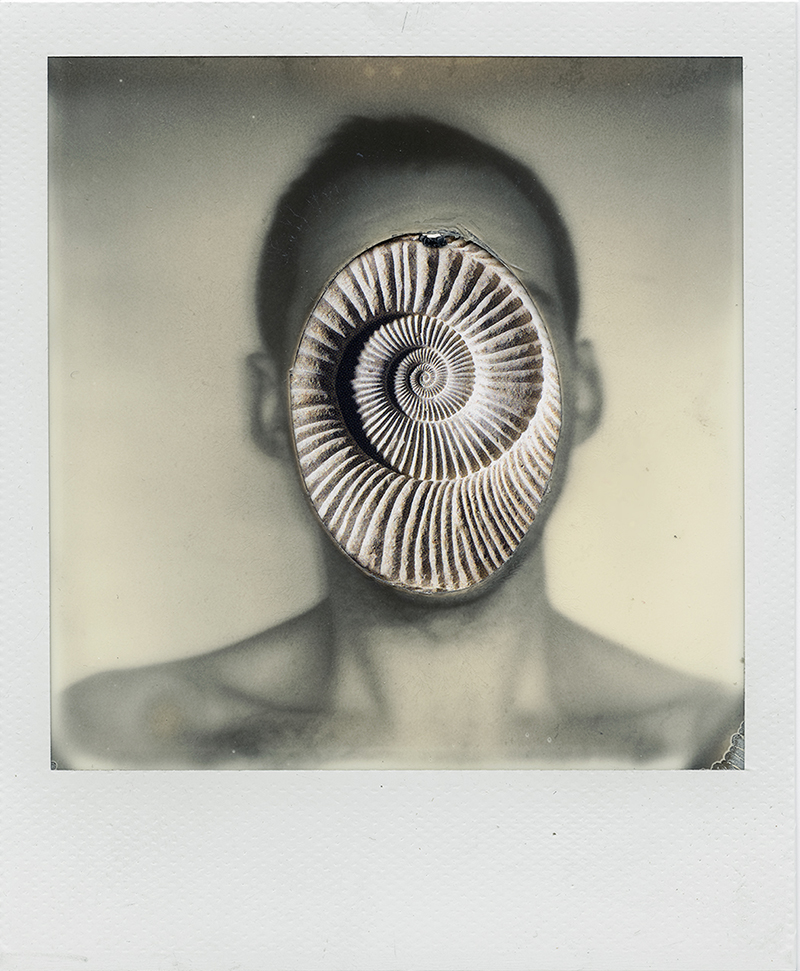

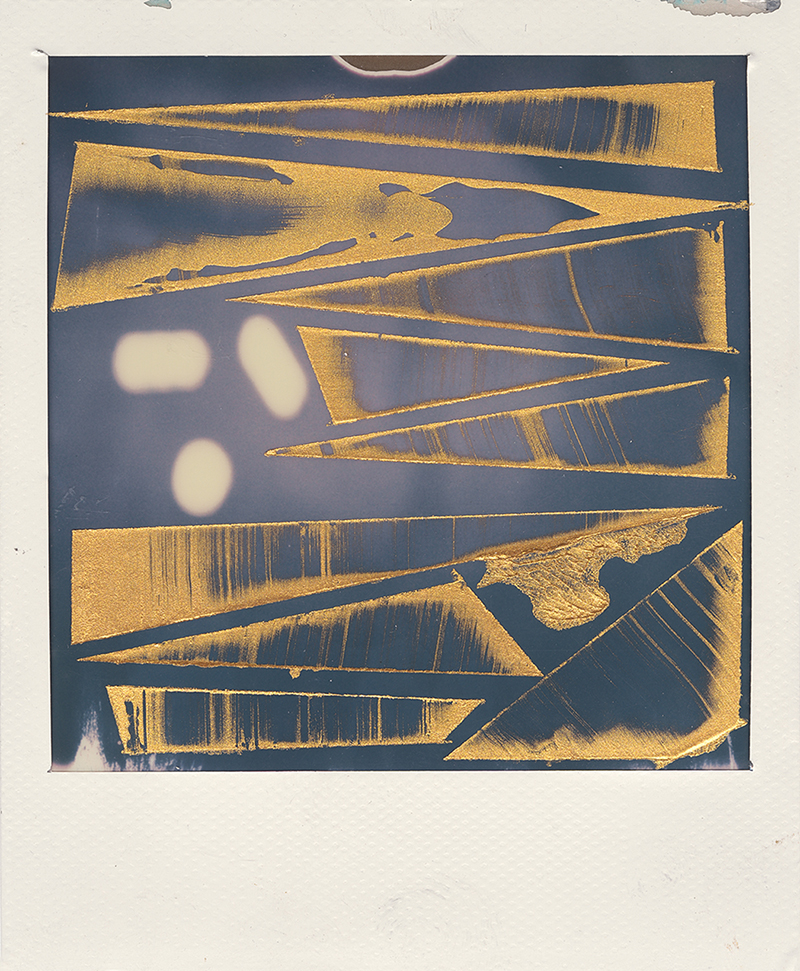

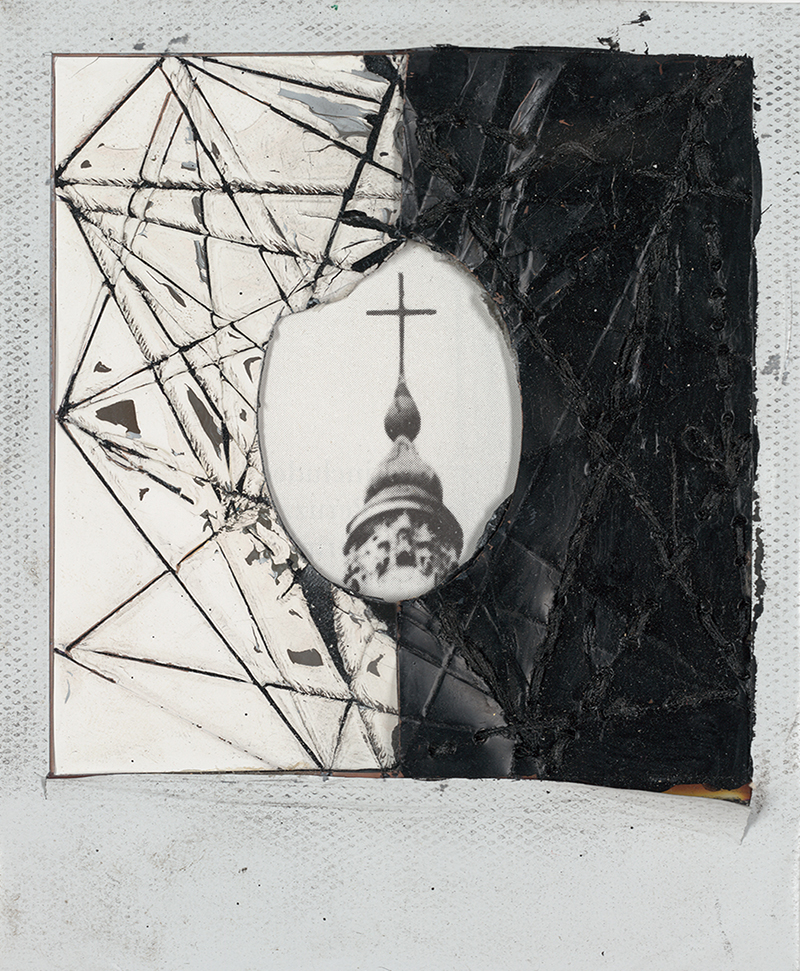

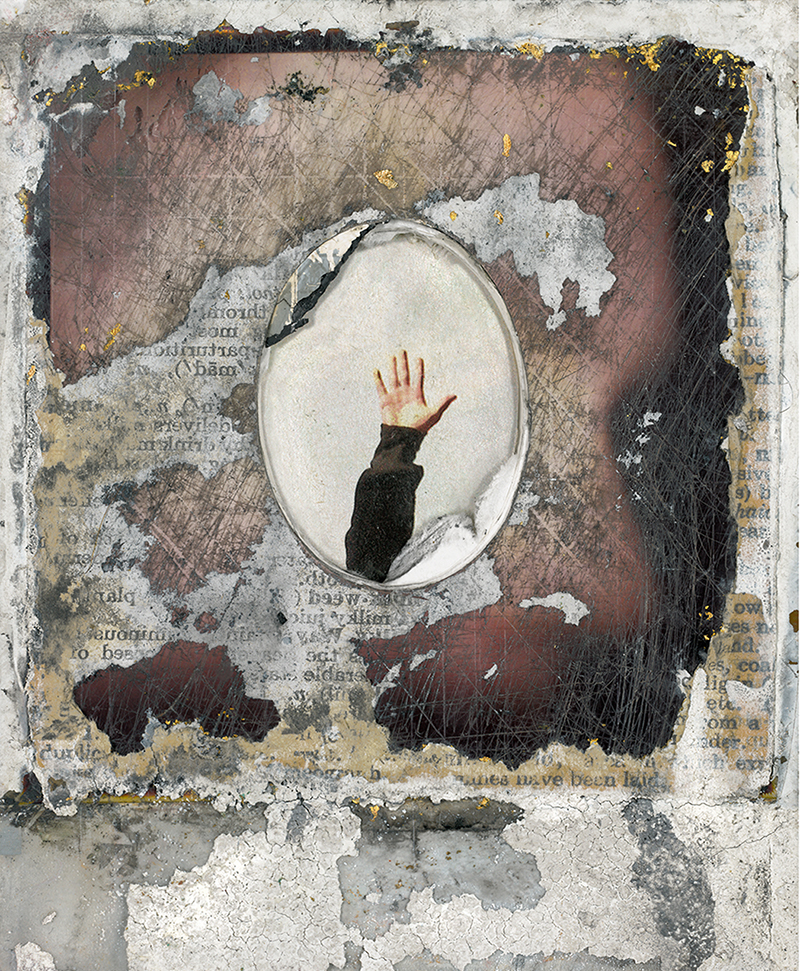

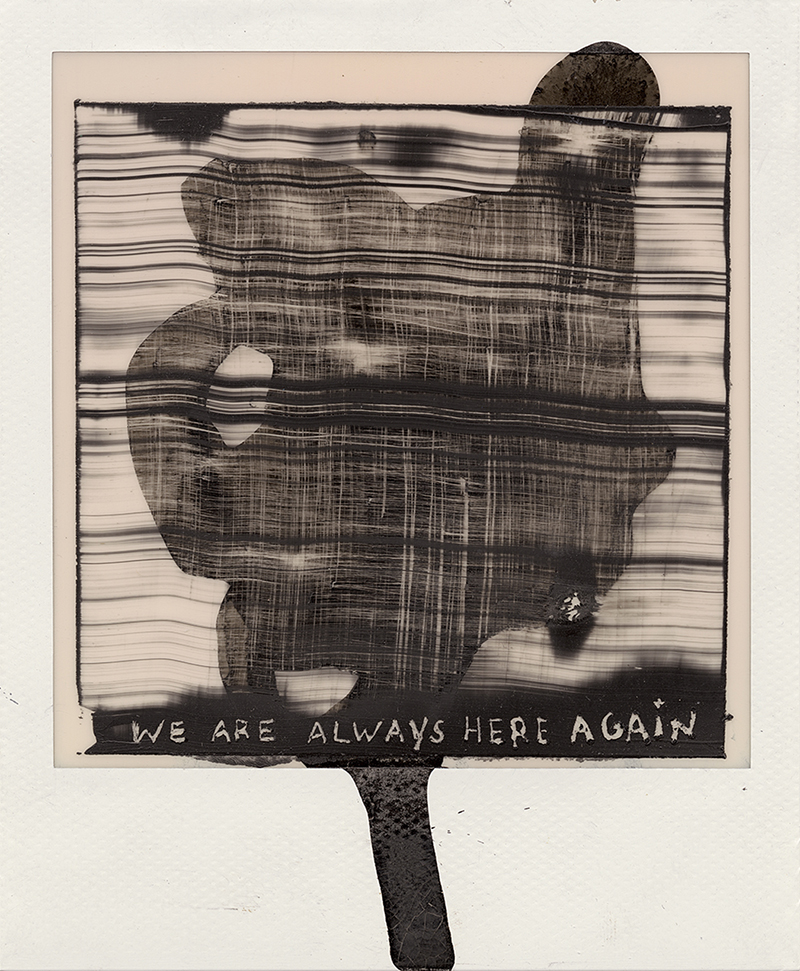

My work largely deals with an excavation of the self, with interest in duality and fragmental storytelling through visual representation, conveying a sense of contemplation and nostalgia, thus allowing the viewer to connect on both a personal and aesthetic level. Set in a state of flux, each work presents a teetering of truths and lies, light versus dark, and all passages between life, death and rebirth. The cumulative narrative comes to represent a portrait of what shapes us, while embodying the deluge of all that was forgotten or surplus to existence.

Kyra Schmidt: Can you start by talking a little bit about your art practice? What led you to this experimental Polaroid series?

Christopher E Manning: My practice is fairly multi-faceted. I tend to work in whatever medium fits the bill or conceptually applies to that particular moment. The principal mediums within my practice are photography, painting, drawing, collage, printmaking and sculpture in tandem. I work on around 100-150 pieces simultaneously, Polaroids, Mediums (mixed media works on paper), Chandeliers (hanging found object-sculptures) and of course sketchbooks. So my studio has a lot going on, all the time. This tends to work best with the way I think and allows for an even amount of concurrent successes and failures, which trade places depending on the day.

How the Polaroids got started really goes back to my childhood. As an 80’s kid in the U.S., Polaroids were just there – ever present so to say. I’d grab my parent’s camera and take endless pictures of my soccer trophies, action figures, my tuxedo cat Stripey, all facets of my youthful life. I used the camera as a way to document and consequently cement the inhabitants of time around me. This process has followed me throughout my life and work. Having obsessive-compulsive disorder, the repetitive and immediate nature of the instant photograph appeals to me. It’s a ritual, a way to save a memory or a period of life – a habitual moment logged into the Dewey decimal system of the collective unconscious.

Around 2004, this documentation began turning into something else. Polaroid film was abundant and cheap, so I borrowed my parents Polaroid Sun 600 (16 years later I am still “borrowing” it…). Back then I was a real insomniac, so I went out and took pictures of energy sources. These ranged from white electrical outlets on white walls, blurry gold light switches, bursting fluorescent lights in the night sky and self portraits of my own frozen energy. The overall conceptual backbone was rooted in philosophies found in Japanese sumi-e ink paintings, capturing the spirit or essence of the physical moment married to my active psyche. Juxtaposing the internal versus the external, light versus dark – these were early concepts that fascinated me.

After collecting so many moments, I began to see these instants as fragments of tangible memory – a portrait of what has, will, and always form me. But often looking back on a Polaroid, that moment was just the surface. There were feelings, expressions and images that needed to be revealed or reflected upon with additional commentary. Consequently the process led to excavating time, covering a vulnerability/moment needing to be forgotten or amending memory with footnotes.

This idea of physical excavation of an image (adopted from Willem de Kooning’s painting of the same name) started with techniques found in intaglio printmaking. I treated the photo as an etching plate, scratching into the image, covering it with printing ink, and rubbing away the excess ink but instead of printing, I just let the ink dry in the grooves, as inking the plate was my favorite part of the printmaking process anyway. These leftover lines made bare the unseen energy of said captured moment, they were the subtitles I was looking for.

My experiments and the series in general really started there, in my college dorm room, trying to make sense of myself during those nights. Polaroids became the cornerstone to the whole process and largely have influenced all other work in my overall practice.

Kyra Schmidt: Your photographs very much embody an in-between space (more of a sensation of being-in-the-world than the world itself). You cover this in your statement and above, too. They also speak to the liminal self; the blurred lines between who we are, who we want to be, where we’re going.. I could go on and on. Can you speak to the linkage between image, material, and meaning, and how they interrelate?

Christopher E Manning: The in-between is what interests me most. I’ve always been fascinated by myths like Janus, the two faced Roman god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, and endings; the Gnostic god Abraxas in context of Herman Hesse’s Damien, a god in-between the holy and the sinner; and characters like Raskolnikov from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Who we were, what we hide, what we want to expose, who we really are and what we wish we could be. The fluctuating space in between these questions and their ambiguous answers is where I like to dwell.

Polaroids are the initial capturing. Some moments are significant, others very much not, but both retain the same potency as significant. I continuously shoot so there are always a plethora of photos sitting around the studio in various states of completion. Gestation periods vary with each image. I go through phases of really loving an image, completely hating it (sometimes because I love it), throwing it in a drawer, only to unearth the thing a few months or even years later. Typically it comes down to a simple action, “change something”.

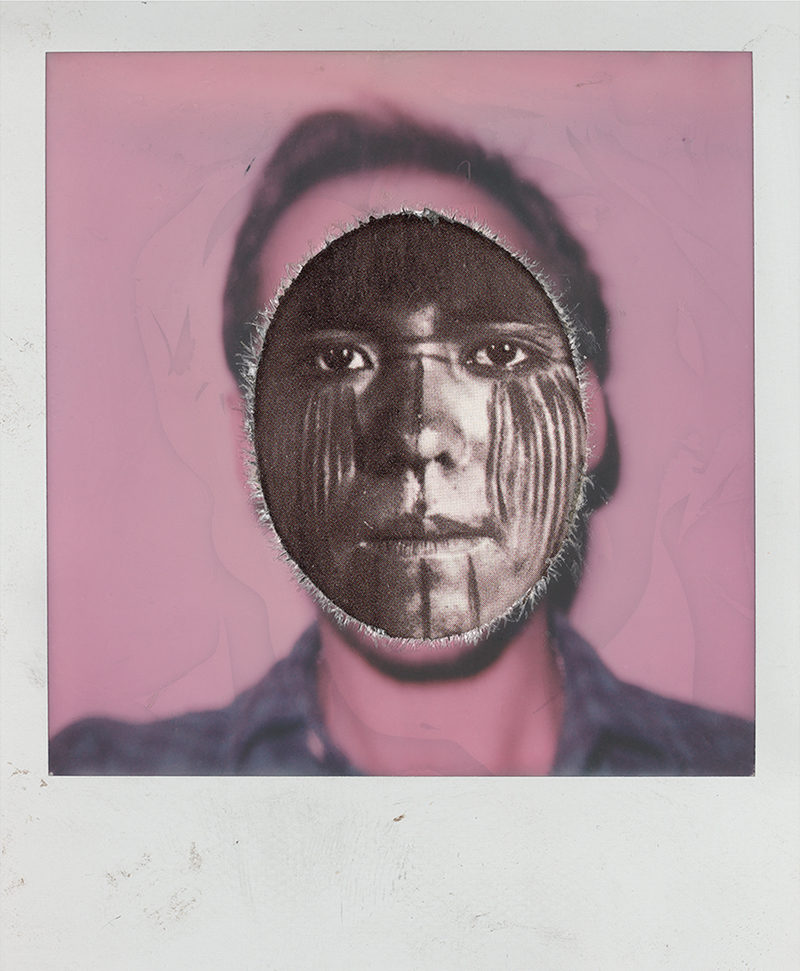

This is achieved through the literal archaeological excavation of an image (think Indiana Jones and the Lost City of Tanis in Raiders of the Lost Ark), which often includes cutting through caustic layers to reveal what is hidden beneath the surface. I often do this through the oval vignette or window you’ll see when I cut through my face or an image. The physical oval is cut using a stone my good friend Bern Richards, who is a Native American White Feather Healer, gave to me, which has forever been my template and in my own spiritual sense is a window to the inner.

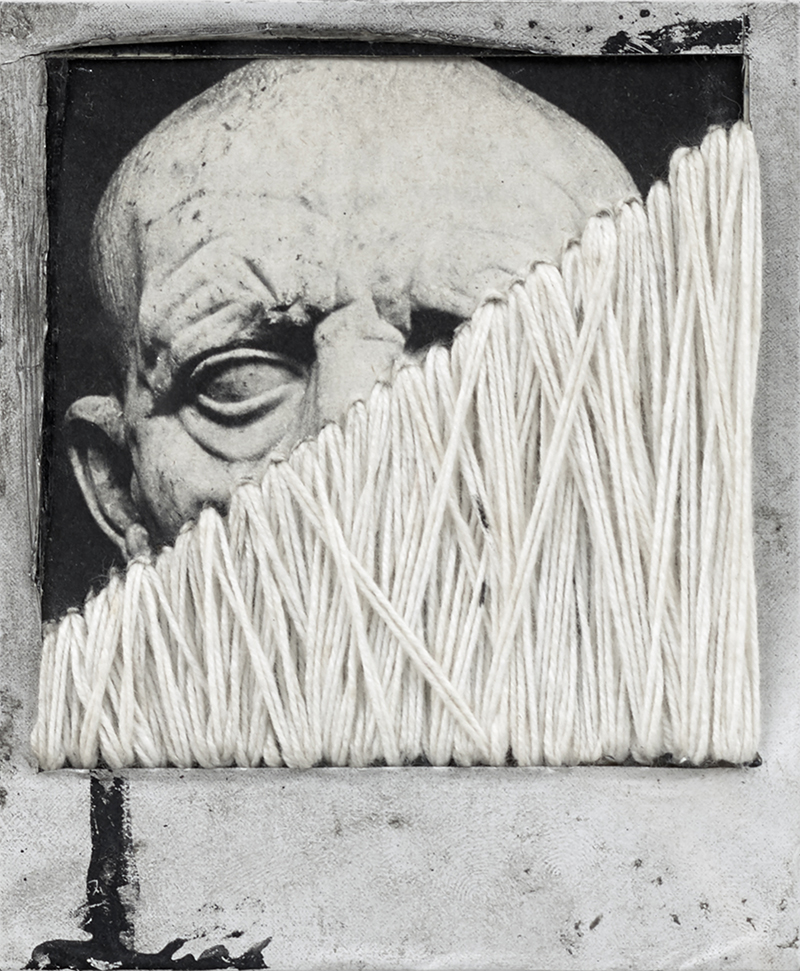

When covering an image, the process is different while the range of media are similar. Thread is used to bind, carefully mending/stitching while obscuring. Acrylic paint or ink covers a landscape to make a once clear view opaque, while bonding the internal world with external. Often I’ll draw on portraits or moments, adding a gestural energy or hand written text.

Works are constantly manipulated. What was once unearthed or covered will down the road (sometimes years later) be completely changed. Fluctuating between successful material to seemingly useless failed works. Still, if it weren’t for errors within my process, I doubt progress would be possible. I thrive on it. Without falter, I don’t believe we would get very far or learn very much. I aim to show these aspects of life concurrently; successes, failures and that grey area in between.

In the end, the image is just the surface – the material added, creation or destruction is dialogue. All actions are a reflection, often over time. The Polaroids are flexible articles of life. All meaning within this equation is a bit of an echo. I most like works that make the least sense to me but yet I can’t change them…sometimes I discover meaning over time, that meditation is peaceful in today’s world.

Kyra Schmidt: There are recurring symbols throughout the book – hands, the sun/circle, various faces – are these purposeful signifiers?

Christopher E Manning: These symbols have become a visual language for me, collaged personal hieroglyphs really. I regularly cut images out of my collection of vintage art history textbooks, 1970’s magazines (great color saturation!), botany handbooks, The New York Times, fashion magazines, National Geographic (70’s to early 90’s), 1800’s etiquette guides, antique books for obscure word combos/titles but the list is endless. These images come to represent the undercurrents of what exists in the subterranean self.

Hands always represent a reach, think about Adam’s reach towards God in the Sistine Chapel but perhaps in my images there’s no God to reach for. It’s an isolated reach without a narrative to communicate response. We reach to escape, we reach for worth, we reach for what we cannot attain and sometimes we still reach for a meaning to it all.

Suns/circles are energy (mentioned previously) and when seen through the lens of a camera, they create a true Mandala when shot right. These mandalas originated back in 2007 when I was a guard at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum (where I’m currently the Exhibitions Manager). Amidst the long quiet days, I was privileged enough to be able to watch a group of Buddhist Monks build a sand mandala over a period of a week. It was a beautiful, slow, agonizingly precise process and in the end, as typical with tradition, they simply swept the mandala away. This had a great impact on me as the entire process was perfectly entropic. So these suns or circles are a search for energy and chaos within the order of a simple frame.

Faces are masks but ones beneath our corporeal surface. Using source primarily ethnographic imagery, I like to make history concurrent with the present. We are both in the past yet in the present simultaneously; time, sex and race become fluid in my images. This may be our current life, other lives lived or energy just still with us. Sometimes it’s who we really see ourselves as. Or perhaps a mask beneath a mask covering the whole thing. Regardless, it becomes an identity, I don’t mean to say literally that the masks I use are me or the appropriation defines me but I have a moment where I feel a kinship and have to act on it.

Kyra Schmidt: Truly, your studio space sounds like a magical labyrinth.

Christopher E Manning: My studio is in the basement of a lake house about an hour outside NYC. It was a complete bomb when I moved in, musty astroturf on the floor, obvious water damage from Hurricane Sandy, two refrigerators from the 1970’s, a giant truck tire, dust everywhere. But my landlord let me do whatever I wanted down there, so I cleaned up the entire space, built walls, installed lighting, made shelving, constructed workbenches and made sure the space was moisture free. Now after almost three years of being here it does have a certain strange magic to it, plus a nice view of the lake, which I’m not complaining about.

Kyra Schmidt: With so much imagery did you find it difficult to edit and sequence the imagery into book form?

Christopher E Manning: The editing was an extraordinarily difficult process. I’ve never actually counted but a low ball estimate of the amount of Polaroids I have produced would most likely be give or take 1,000 works as of now. Luckily I had some help when editing from my good friend Lizzie Stein, who wrote an essay in the book and has known my work since it’s infancy. My wife Michelle was also essential to the process as she has lived the work with me. Having two people I very much trust helped remove some sentimentality in our selections and allowed for maximum creative criticism without emotions getting involved. My personal community is what forges the work, having them involved in my process is something I’ve come to enjoy and respect.

I keep a very cohesive digital archive. Back in 2009, I was fortunate enough to work as a studio intern for Tom Sachs, during that time there was a hand written note on the office wall that went something along the lines of “nothing leaves the studio without a picture”, I still adhere to this principle. So I uploaded a majority of my archive for Lizzie, we would Facetime and discuss options. One of the benefits of working with someone who has known my work for so long is that we could identify themes, processes and concepts that was important to the evolution of the Polaroids.

One thing I learned from Lizzie, as she had previously produced books with artists in her professional career and now working for The Freer|Sackler at The Smithsonian Institute, was the process of printing out every possible image that I might use to physically storyboard the book. This gave us the ability to quickly manipulate pairs of works to create small dialogues while seeing the book all at once. It was also amazingly satisfying to discard the excess images by cutting them up into scrap paper for my studio when done.

As for the sequencing, I thought of the book as a small show. Typically I install the Polaroids directly to the wall in large grids bursting from corners or small intimate groupings. A few of these installation images are featured in Lizzie’s essay. A language starts to develop in these small formations. I alternate themes depending on individual and collective content but also as events would occur if life were to be displayed simultaneously and perhaps overwhelmingly on a flat plane. Like in movies having your life flash before your eyes.

Given the size of a Polaroid, there is an intimacy to the image, a magnetism pulling the viewer into an experience only one or two people can see at a time. I love this about small works, it is what makes them powerful. So in the book, each spread is set up as if two pieces were hung on a gallery wall and conversation is generated between them. Events and moments alternate but sometimes repeat at random, mirroring what I do with the themes I work with – there is a logic but it’s intentionally not always persistent.

Kyra Schmidt: And your title captures a certain all encompassing beauty too.

Christopher E Manning: My process in general is stated in the title and on the cover of the book. ‘Everything, As Perfect As It Seems’ is written in my handwriting and my Mother’s. Her’s is very precise, Catholic school trained, clear cursive. Mine is dashed, all caps, often a barely legible scrawl. Neither is perfect. What we believe on the surface is perfect, often never is, sometimes it takes an addition of the perceived imperfect to find harmony.

Kyra Schmidt: Lastly.. There are so many Polaroids! Do you have a favorite image within the monograph? Or, is there a particular photograph you feel encompasses the essence of this project?

Christopher E Manning: I try so hard not to have favorites! I find it sticks up my process. But nevertheless it certainly happens.

For the book, I think it’s Self Portrait with Mask (Shell Face). The image features a black and white self portrait with my face cut out revealing an ancient spiraling ammonite shell. This piece presents the contemporary and prehistory simultaneously, beneath everything, we all have the same origins, which are always with us. It also stems from Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and his use of entropy in the work. But I reflect more on the psyche, that through the operations of nature, experience and chance, we all are constantly in a state of transformation. Myself most certainly included.

Kyra Schmidt: Thank you, Christopher, for speaking with me! It has been a wonder to learn about your creative process and the life of these Polaroids.

To view more of Christopher E Manning’s work please visit his website.

And to order a copy of Christopher’s new book, visit the shop!