Nicholas Widener is a photographer based in Chattahoochee Hills, GA. He graduated from Georgia College in 2013 with a BA in Mass Communication and the Savannah College of Art and Design with an MFA in Photography in 2019. Last year Nicholas founded the Film program at his high school alma mater, Woodward Academy. He is presently teaching film studies and coaching cross country and track and field. Work from Both Sides of the Old Road has been featured in group exhibitions at the Chatt Hills Co-Op, Serenbe Art Farm, and Slow Exposures. He exhibited two solo shows premiering work from the book at Woodward Academy and Theatrical Outfit in Atlanta.

“I use photo-genealogy in Both Sides of the Old Road to excavate my familial roots. Combining archival letters, old family photographs, and objects with my own portraits and landscapes, I endeavor to tell the story of my ancestral origins in the Black Belt region of Alabama. My brother, Andrew Widener, is a genealogist at Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in Washington, D.C. He has researched, collected, and identified information and oddities about our family for over a decade. Halfway through this odyssey, I began to ride along with him to the Black Belt where the stories he gathered turned into visual imagery.

William Christenberry’s photographic ruminations on place and time have had a lasting impact on me. He was born in the Black Belt, not far from where I shot most of this work. Other great photographers like Walker Evans and Andrew Moore have tread there, too. The work of eminent Southerners like Sally Mann, William Eggleston, Harper Lee, and Jeff Nichols have had an influence on me and my topophilia for the South.

All in all, I seek to situate and understand my place among the generations that came before and the generations yet to come by searching for the ties that bind them together.”

Sydney Gillum: From viewing your book, “Both Sides of the Old Road,” it becomes clear that family is very important to you. How did that impact the book? What was your inspiration?

Nicholas Widener: At first, when I began accompanying my brother to Alabama on a genealogy trip, I was just shooting. I wasn’t exactly sure what to shoot, but I shot the land I knew was significant to our ancestors. My brother had to explain a lot of the landmarks and history to me. He still does this — I am always trying to keep up with the new information he is learning and relaying. Without family, this book couldn’t exist. Family is in every frame — whether they can be seen or not. The real intent of creating this book was to try to understand our ancestors. And hopefully, preserve their story for our descendants. In “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” the voodoo priestess says, “To understand the living, you gotta commune with the dead.”

SG: What does the title, “Both Sides of the Old Road,” mean to you?

NW: I had a couple of titles for the book before settling on “Both Sides of the Old Road.” None of them had a nice ring to them. This title really spoke to me because it represented property that our ancestors used to live on. It was a place, still is a place, where we can go and know with certainty that our ancestors dwelled there. There’s a spiritual force present when you’re on that land. It speaks to you. In the book, you can see the land on page 77 and then again on pages 102 – 103. The actual phrase comes from an article my brother wrote as he was describing the property. Many of the roads traveled there feel old. Maybe older than they are. That helps me to be able to populate them with my ancestors, though. They feel storied.

SG: I really appreciate your willingness to share your family and experiences with the reader of your book. Why did you deem it important to add the personal touches of handwritten letters, verses, and old family photos? How does it impact the story you’re trying to tell?

NW: There’s a really grand story to tell here about our family. I suspect most folks have a similar story to tell, too. The ephemera of letters, quilts, and archive photos are all paramount to that story. It’s not just mine to tell, so I invited my ancestors into the project. Everything in the book that I did not shoot adds more depth to the story. The book opens with a collage of stories collected in a letter from our Great-Grandmother, a natural storyteller herself. From her letter, the people and places unfold. Verses from her Bible that she deemed important are coupled with my photos. Her handwriting of the hymn “Amazing Grace” is paired with familial quilts, and at the end of the book, my grandfather’s drawing of our family tree is included. These writings and verses, of course, hold more significance to our family, but excluding them would have left the story unfinished.

SG: I loved seeing your work accompanied by your brother’s words. How important was that? Was it hard to work with a sibling? How did the idea of working together come about?

NW: Thank you! In the acknowledgments in the book, my brother references how my parents always encouraged us and said that we would one day collaborate on a project. We didn’t know it would be something like this. But it really is the perfect amalgam of our talents. Before I began this project, Andrew had done most of our genealogical research on this side of the family. As he was talking about it and doing more research, I thought I would go along for the ride out of necessity. I had to have something to shoot for one of my graduate classes. It wasn’t hard-working together at all. We don’t really spar at all. Andrew has always been an encouraging advocate of whatever I was working on. Even though this body of work was my graduate thesis, it couldn’t have existed without the research Andrew did and all his support. Having him co-author the book was the obvious choice. Whether we were conscious of it or not at the time, as soon as I started shooting in Alabama seven years ago, we were partners on this journey.

SG: Did you have artistic influences while working on this book?

NW: My biggest influences on this book were some of the obvious preeminent Southern photographers like William Christenberry, William Eggleston, and Sally Mann. Christenberry was born in Alabama, just a county North of where most of the photos were shot. His style and themes of the South and the passage of time were very influential. Eggleston’s book “Election Eve” about the night before Jimmy Carter was elected president, is a wonderful Southern Odyssey. I have always admired his shooting style. I made 15 trips to the Black Belt with a revolving cast of family members, so I draw a lot of comparisons to Eggelston’s trip within my work. Mann’s landscapes are what really resonate with me. She understands how the land can speak. Her work really helped me cultivate my topophilia for the landscape of the South. I was also influenced by Andrew Moore, Kurt Simonson, Sara Marcel, Chuck Heard, and Sarah Christianson.

SG: Is there a specific image that stands out to you the most? Can you tell us the story behind it?

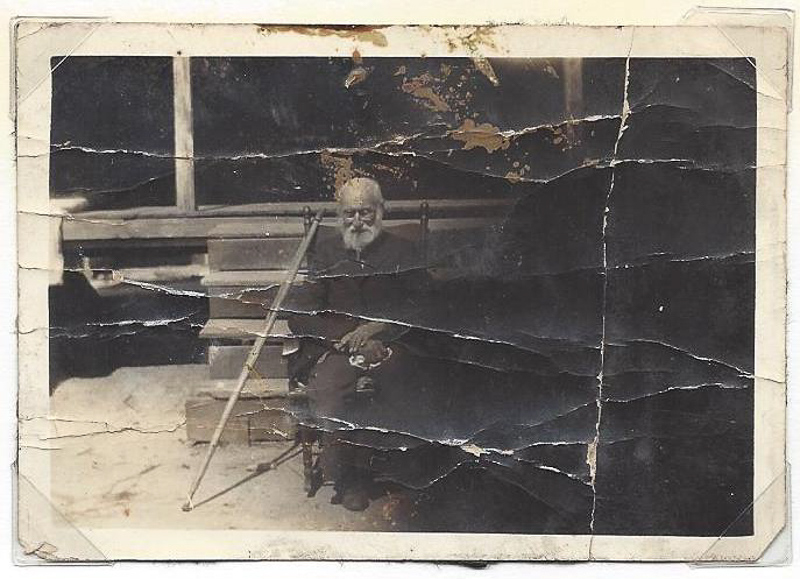

NW: It’s difficult to pick that one special image! But I’ve always been drawn to the portrait of my grandfather on page 25. As I photographed him, my grandfather patiently stood there in the derelict shell of the house he was born in. As with every portrait I shoot, I have to shoot until I have that spark, knowing I got the shot. I am proud of a lot of the landscapes in the book. Especially the footprint in the mud on page 41. It really was a serendipitous moment because that photo was shot on my ancestor’s land. And it was not my footprint. It really was tough narrowing this book down to what you see. I even created another mockup of a book during the editing process. But the portraits tend to have the most interesting stories because they are very personal. Another favorite portrait of mine is Cousin Barbara on page 49. This was actually the first portrait I took for the series. Barbara is outside of the McKinley Baptist Church, which my fifth-great-grandfather John Talbert pastored in the 1860s. She is one of only two living members of the church.

SG: If you had to explain your book to a prospective reader, what would you say?

NW: I am not sure where I first saw the word “photogenealogy,” but after I did, I knew that’s what I was doing. This book is the marriage of photography and genealogy. My brother and I are trying to explore our roots through genealogy and expound upon them through photography. We have also often used the phrase fraternal odyssey to describe our travels into the lands of our ancestors. So, essentially, the book is a photogenealogical, fraternal odyssey into the Black Belt of Alabama. I’m not sure if that’s too wordy or not, but that’s how I see it. I also believe this book is a way for us to make a place for ourselves in our family history, somewhere amongst the generations that came before and the generations yet to come. We are looking for all the ties that bind us together.

SG: Are there any last things you would like readers to know about you or your book?

NW: This body of work and book took a lot of time and exhaustive efforts to create. But it is such a joy to have it finished. My brother and I talk a lot about having this book done for posterity, and that’s really important to us. We really draw so many connections to how some of our relatives also told stories. After we finished it, we finally saw it in print; it was such a humbling moment. After my grandfather, to whom the book is dedicated, saw it and said he was proud of us, I knew all the effort was worthwhile. We had a book signing at the end of May, and a lot of family and friends showed up and supported us. Despite the book being published for anyone to see, it still feels so intimate; I feel as if every time we sell a book, we are giving out a family album.

If you’re interested in Nicholas Widener’s book please head over and check it out!

To view more of Nicholas Widener’s work please view his website.