Bay Area artist Feldsott, one of the youngest artists to ever exhibit at SFMOMA in 1975, disappeared from the art world after becoming disillusioned with its corporate demands. After getting caught up in a world of drugs, politics, and uprising in South America, and then studying traditional medicine there for more than 25 years, Feldsott remerged to exhibit again and is opening up about his time creating a prolific body of work in obscurity and how art heals communities.

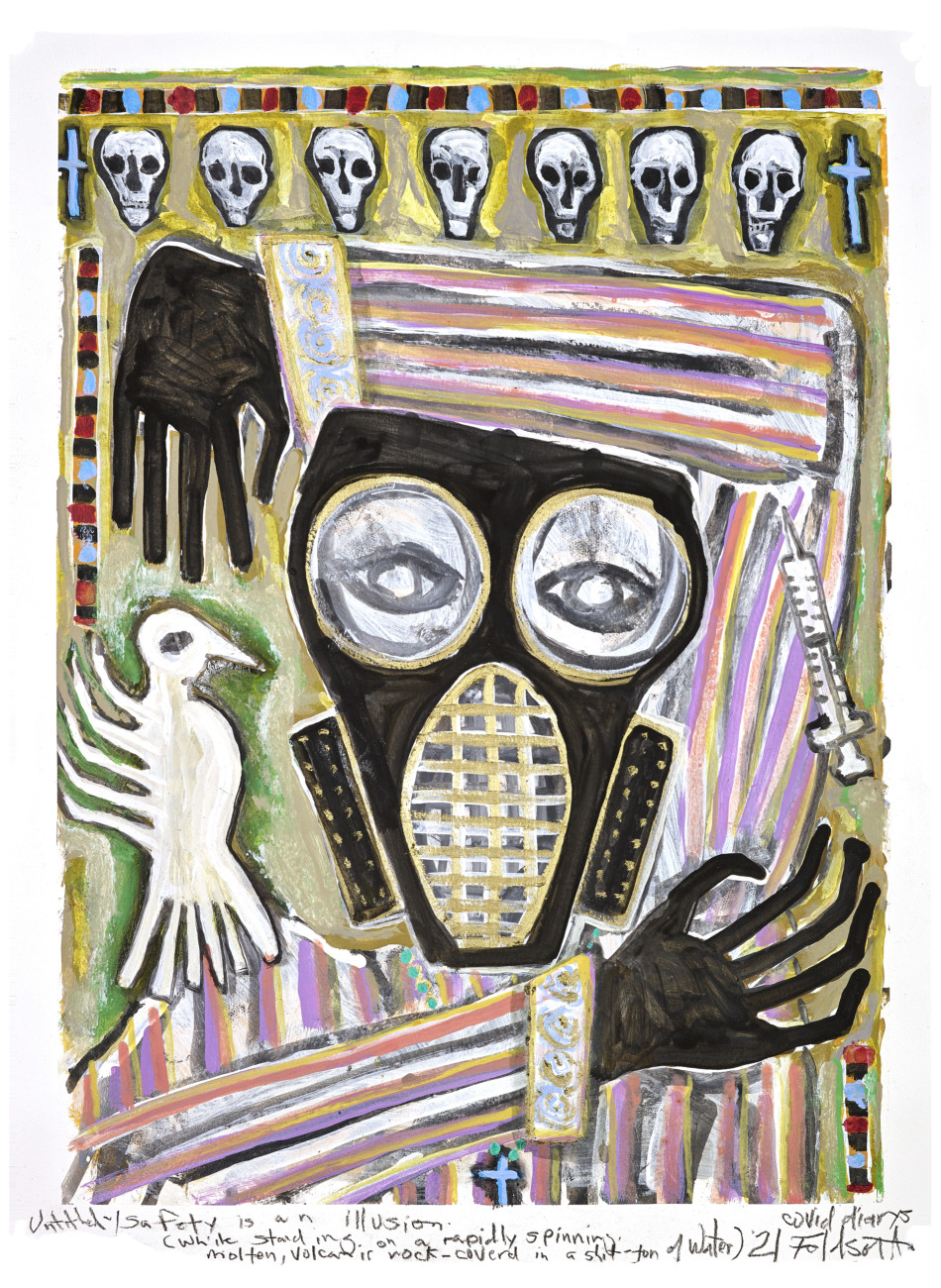

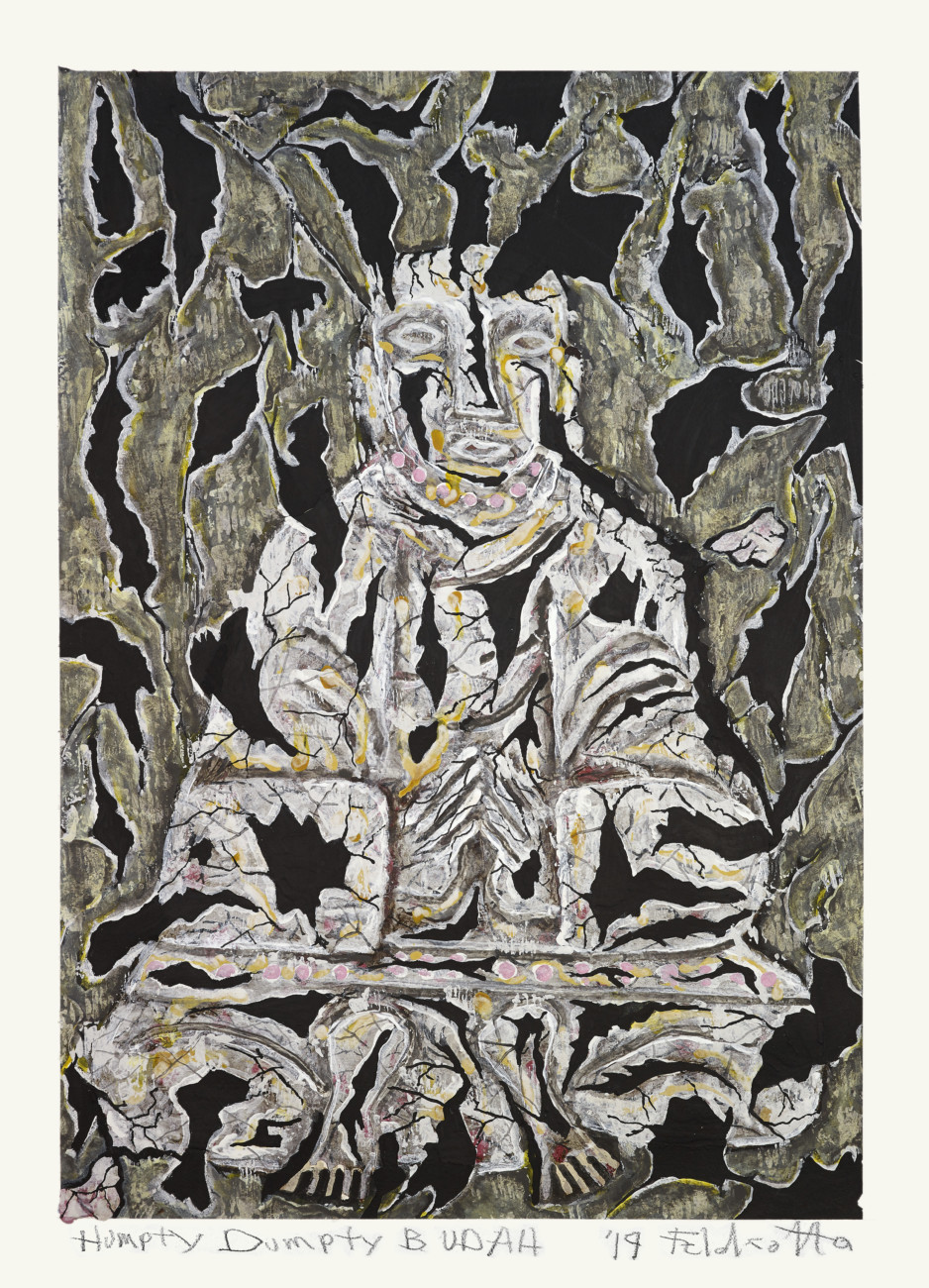

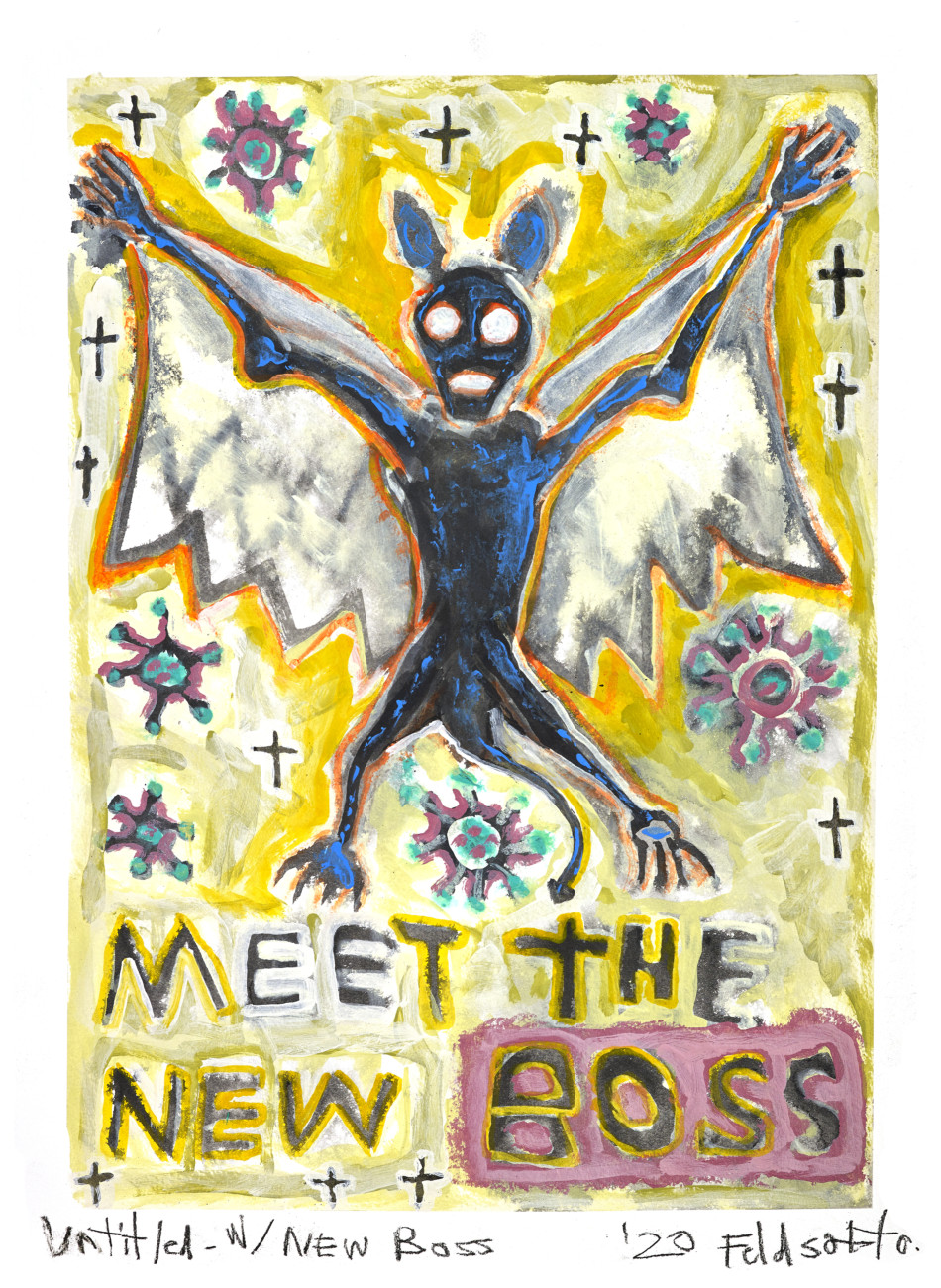

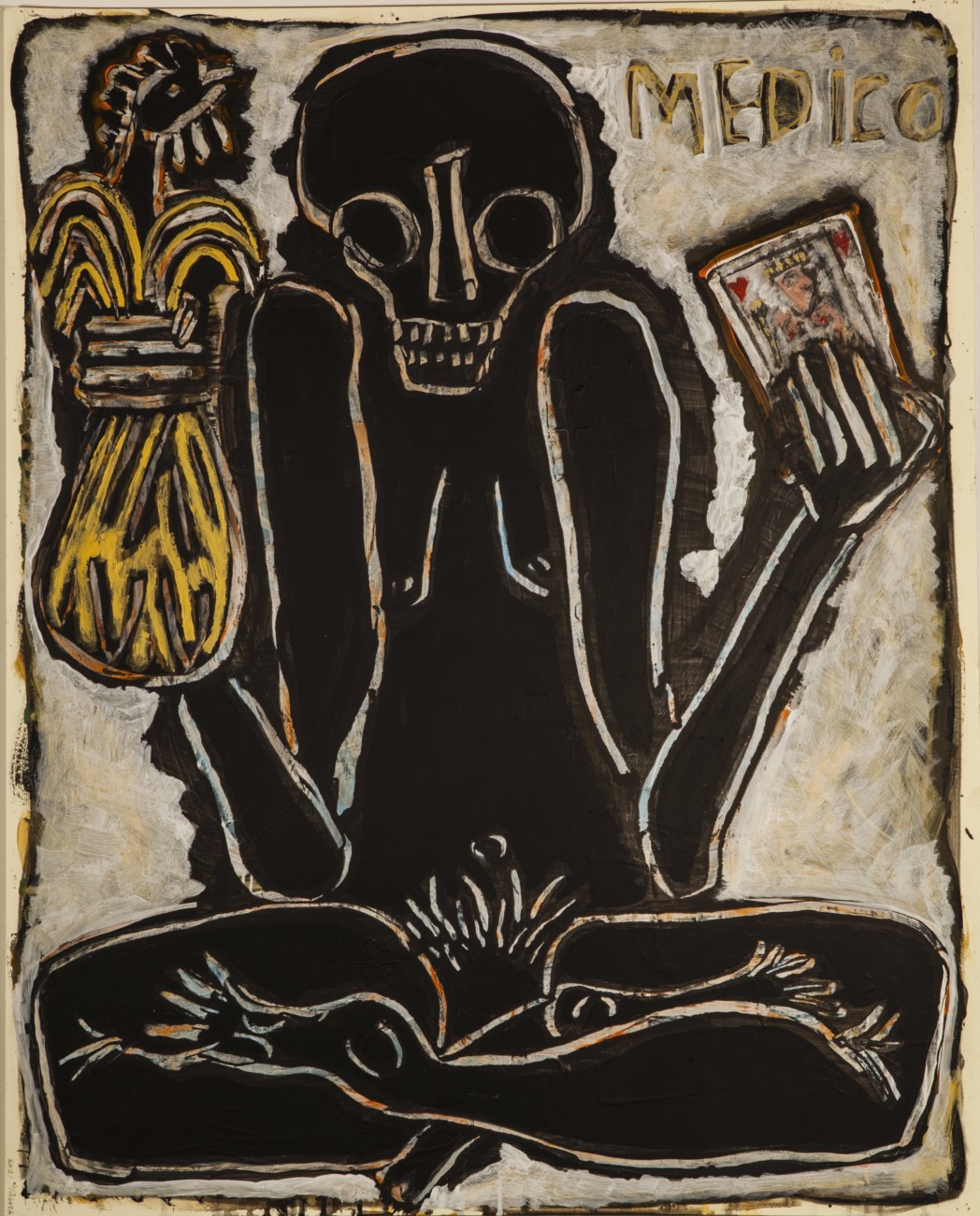

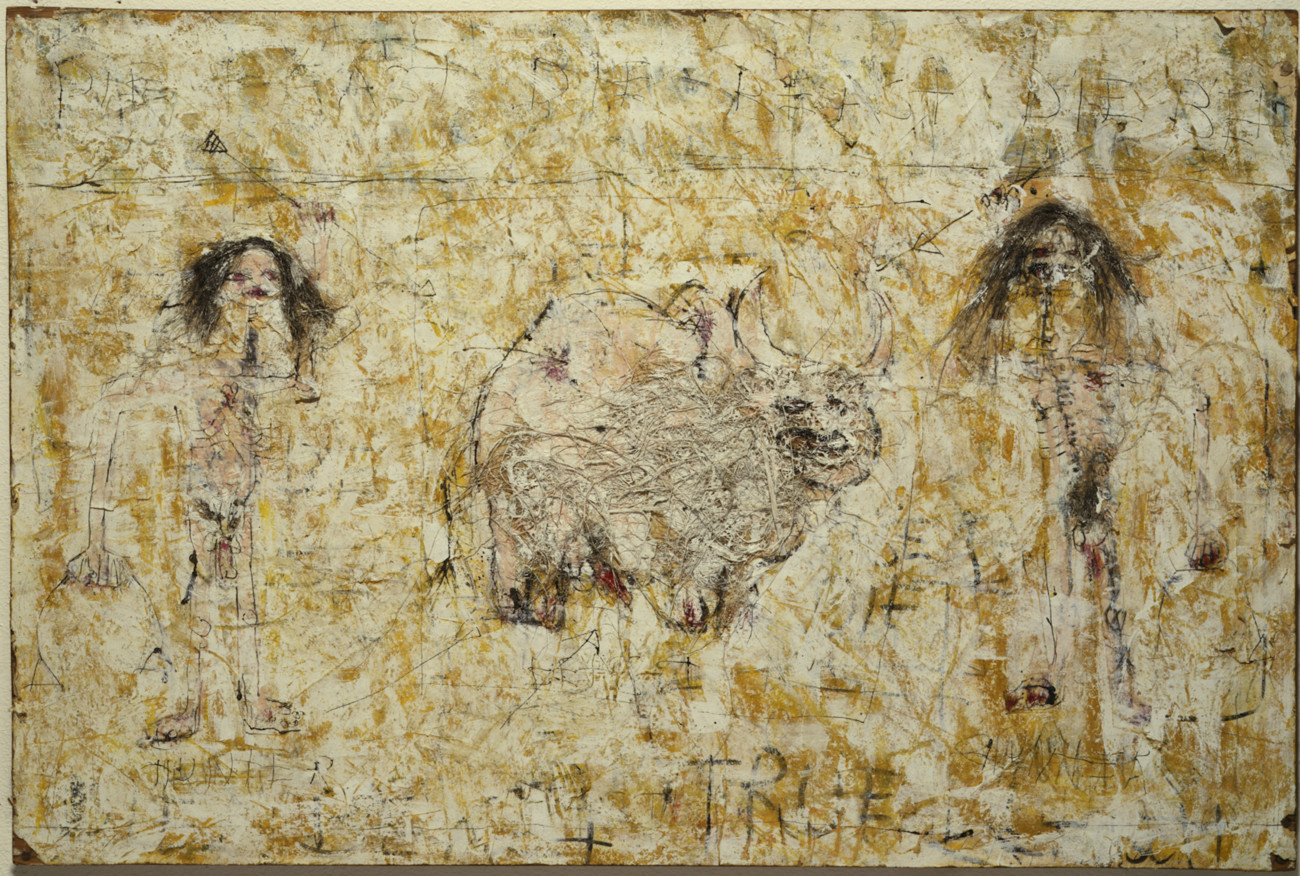

Feldsott’s paintings retain their influences from the Beat poets and jazz musicians of the 1970s while also examining the issues of our current moment: from the use of torture to borders to the Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout all of this work, Feldsott’s signature enigmatic, spiritual, and mythologically-charged imagery underscores his “art as medicine” approach to art-making. He will be exhibiting at SUNY at Westbury Amelie A. Wallace Gallery in September.

Emerald Arguelles: Can you discuss your introduction to the arts?

Feldsott: I started making art at a very young age. I was eight or nine years old and felt riveted to creating images and monsters. I didn’t have any context for it or intellectual ideas about it. It was just something that I was doing, and I had been more interested in, as opposed to the other kinds of games that other children were playing. I was becoming more and more internal, and participating in this art-making process was compelling and fascinating. Many years later, through more experience, there was context built around that creative process. It wasn’t until I was in high school that I was introduced to the larger world of art if you can call it that. I became aware that other people participated in and devoted their lives to art. That was the beginning of a more extensive awareness of art as a world and a way of life. That came to me as a teenager. And making art grew from there.

EA: What does art mean to you? Is there a way you define your own work?

F: That’s an incredibly huge question. For me, art acts as a medium or translation between the visible and the invisible world. It’s a conduit for all kinds of experiences to translate and become embodied somehow, whether that’s music or spoken word or dance or visual arts or conceptual art—whatever it is, there’s a translation of what is almost untouchable. Art triggers in us a kind of knowledge or understanding. Art, in its best ways, inspires us and cleans away the cobwebs that dull us and challenge us. It triggers some kind of knowing or understanding that propels us into a wider field of consciousness.

EA: What led to your disappearance from the art world in the late 1970s?

F: When I was younger, I was very focused on the making of art. The art world gave me extraordinary opportunities, and my work was exciting to people. There was a growing collector base that was developing. There was interest in curators from museums. So I was rolling with it, things asymmetrical to somebody my age and starting their art career. But as often happens in that situation, there’s a commodification or commercialization of that process. In other words, becoming known for certain kinds of work or specific outputs lent itself to feeling like other forces were controlling my approach in the studio. So there was a pressure put on me in my studio and on my process to produce work identifiable as mine and in the genre or lineage of whatever it was I was doing at the time.

My arrogance, self-righteousness, and social and political outrage resulted in feeling taken aback in my youth, and I became angry and resentful. Several events occurred that had to do with both commercial warnings given to me and curatorial censorship decisions made about my work. So, I decided I would continue making art and being involved in my studio, but not in the commercial art world. I stopped participating in shows and trying to sell my work. That retreat went on for almost 20 years. It was amazing because it allowed me to make art in a way: “I answer to nobody.”

EA: What led to the decision to leave the United States?

F: My decision to go to South America had nothing to do with art. I’ve always had to hustle and do odd jobs to earn a living because I wasn’t making a living with my art because I was refusing to show it. During one of these jobs, this guy I was working with said we had to save the rainforest. In the mid-1980s, environmental awareness wasn’t at the level of conversation it is now. But I was struck by this, and I told my wife that I would go with this guy to save the rainforest. It was this absurd Quixotic mission. We arrived in southern Mexico, and I’m sure we seemed like totally unhinged, lunatic gringos. We caused enough disturbance that finally, someone got in touch with us. This social anthropologist at the University of Mexico, Luisa Pare, specialized in working with Indigenous forests and Indigenous communities that live on or near the borders of forest lands. And then one thing led to another. The next thing I know, we’re doing what was at the time this kind of cutting-edge work to empower indigenous communities. These experiences led me to work with various people in Western Amazonia.

You can imagine being such a foreigner in such a different kind of world and cultural ecosystem, and one could feel odd. And yet, at the same time, I felt very peaceful and very much like this was a place that somehow I recognized.

EA: What did you learn during your time in South America?

F: I found myself becoming more and more peaceful there. In other words, there were certain qualities about the way of life there that resonated with me. There was a quietness of mind that I found very restorative.

I realized there were generational wisdom, knowledge, and traditions that these people held. So while I initially thought I was going there to help them, like I was going there to help them save the rainforest, I realized that I was there to get help. It was a complete transformation. Of course, many things happened and many adventures, and many different moments on the journey there, but that realization changed the whole flavor of my purpose there. I was there to restore or reconstitute some internal architecture in me that had been quite damaged and wasn’t functioning properly.

EA: How has traditional medicine influenced your work?

F: The people I met abroad have this wisdom, and these generational traditions, healing traditions, absolutely helped to kind of reformat me. If you look at my work from the early 70s, you can see that the work is very primordial, shamanic, all that stuff. It’s not like I’m intentionally doing that. That’s the organic expression coming out of my hand. I didn’t have any context for it. I’m doing that in the 70s; I’m strung out, struggling in many ways, and I don’t know what to make of it. These people seemed to understand those energies moving in me and help reframe them so that instead of those energies being chaotic and destructive, they became solidified and healthy and resonant. But that process took years—it wasn’t instantaneous.

In the beginning, the art-making was all about me, my expression, and whatever was happening in my studio. As I became older and more integrated, I began to see life from a different perspective. I’m inspired to live a meaningful, supportive, and helpful life for myself and the people around me: my family, extended family, friends, community, whoever. Suddenly, art becomes a tool, and it becomes something that has some other meaning. I would rather be inspired to make art that contributes something that is uplifting or moves people in a way that awakens awareness on some level.

EA: How has painting healed you?

F: For me, making art is an entirely organic process. The art is reflective. It has specific windows into myself, my life, and my struggles. At this point in my life, I would say that art is a spiritual practice of knowing what I know. It brings me into deep communication with myself and contact with the energies around me, which are not just me. Those energies inside myself are in communion.

EA: What are you looking forward to next?

F: I feel grateful that I’m still in a place in my life where I’m able to produce work. I’m still curious, I’m still passionate, and I’m still excited about what’s happening in my studio, which is continually unfolding. I’m always enthusiastic about the next series of paintings that are beginning. All of that is immensely satisfying.

Watching my kids and grandkids evolve in their lives and the projects they’re doing—is the ultimate blessing. To realize that maybe some of these stories and some of these things I’ve experienced have value or meaning to somebody and their journey. Some of this may prove helpful or valuable in some way, small or large. It is a blessing that my life continues to have the purpose and meaning to still engage completely. That’s what I’m grateful for right now.

Over the summer, we’re gearing up for an exhibition at SUNY University in New York. We’re presenting a good selection from the COVID Diaries and paintings from early 2000 up until the present.