In 1987, in search of the “American Dream”, Karolina Karlic’s family immigrated from communist Poland to Detroit MI- where her father began work in the auto industry. From this uprooted childhood, her practice concentrates on the human effects of social upheaval.

We asked our friend Matt Szal to have a conversation with Karlic about the

inspiration behind her most recent book, Elementarz, the future of her project, and thoughts on her recent Guggenheim Fellowship.

Hello Karolina, how have you been doing?

I’ve been doing well, I recently went to Detroit and then to North Dakota to work on my

current oil boom project. I have been so busy recently that I decided to take a trip

to the desert with some friends to get away for a few days. Now I’m back in Los

Angeles.

That sounds great. How is Detroit’s art scene nowadays?

Its good. It was definitely better at one point when the auto industry was booming.

But it’s tough now. Now there is a lot of pre-censoring that happens. Even for artists stemming from Detroit, like myself. People are very protective of what they have, having been taught to hold onto what might be easily exploited, misrepresented or stolen from them. I guess it might be similar to Texas and being a “Texan artist”, whatever that means? (laughing) I assume both share an interesting sense of pride that is very unique to the insiders– similar to the pride of Detroiters. Detroit curators are aware of this pre-censoring and have starting to invite more international artists through various forms of participation, but with valid caution. The media, for instance, is not helping Detroit’s progress. Shame on them.

Yeah, I know, it’s hard being labeled a Texas artist.

Yeah, geographical labels do not open the discourse that should be there, in fact a lot

of times it shuts it down. Detroit definitely raised me, certain perceptions emerge

from that. I say where I am currently working and living defines each series of work.

You lived in Detroit but you are originally from Poland, right?

Yes, I was born in Poland. My dad taught mechanical engineering, which initially brought

us to the States. We first moved to a trailer park on the Mississippi River. During that first year my mom was about ready to kill my dad. We then moved to Detroit where my dad started work as an engineer.

The Great Migration, is actually a large part of the concept of Elementarz, the migration of African Americans from the south to the ‘rust belt’ (Detroit and Chicago) for work as a response to the growth of the American auto industry in the 90s.

So you’re working in Los Angeles currently. It doesn’t seem like you are making a

lot of work there, rather traveling all over to produce your work?

Right now there are a lot of continual small projects that I am working on. Almost

like “test runs” or dabblings. They aren’t yet truly evolved or as fully formed as my other, more developed, projects. I find that when make pictures you really never know what kind of pictures you are going to make until you go and make mistakes, hate them, and respond to what you have made.

That leads me to what you said in a previous interview about the historical reading and planning you do before you begin your work. What kind of context would you put this series in?

I see Robert Frank’s “The Americans” and the idea of the American road trip as a huge contextual influence. Frank received a Guggenheim Fellowship award in 1955 to travel across the United States and photograph “society”. What most don’t acknowledge is Frank’s keen interest in and more specifically his desire to go to Detroit and make pictures there. Now here we have this Swiss born, Jewish man, set out to make work about Detroit and America, and he was suppose to be objective? Well, this upset a lot of people, you know? He wasn’t an American but [he] was making a solid observation about Americans. He shows this very interesting birth of the American auto industry and I am capturing its shift, collapse and its ending. It is this constant doubling, the back and forth migration, the rise and fall, that I see threading through my work historically.

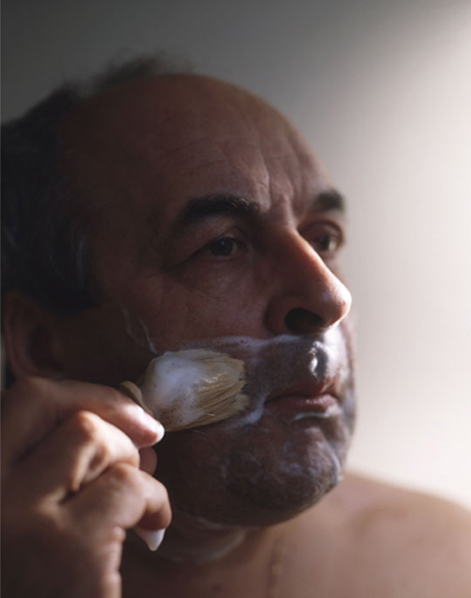

That’s interesting, how do the photographs of your dad shaving or domestic scenes play into this idea?

Most of the images have this air of nostalgia around “things that we make”, specifically, cars. Regardless of whether it’s an Impala from the 70s or a Ford Model-T.

The photograph of the light fixture has three parts really: the old, antique base, the 25-30 year old fixture and the new spirally eco-friendly light bulb. It is about coming

full circle with an old European background into whatever we have become today. The Michael Jackson image is also representative to coming full circle with his death as the only marker of time in Elementarz. We have MJ, the Motown–Jackson Five child star, rising…and falling, taken by the society in which built his fame, ultimately ending in headlines “Michael Jackson was a lonely man.”

And the shaving photographs?

There are five chapters in my book. The second is the all about the engineer- my father. Shaving is a moment of preparation for the day. To look proper for work or making oneself presentable for anything one might aspire to prepare for. There is no better way to show the vulnerability of a grown man. In the book, the first chapter covers human nostalgia, ideologies, and promises. The second focuses on the working man, my father as the subject. The third, the ironic return to a homeland, Poland, for work. The fourth chapter is about apologies and distances to manage in relationships. Lastly, chapter five is the evidence of the economic, industrial collapse.

Robert Frank’s The Americans, this project–Elementarz, and your Sierra Leone project are all in book format. Do you think that these images can stand alone or is it necessary to view these images in this format for what you are trying to communicate?

I think the book format insists that viewers have the option to really study the work in it’s format. It is definitely not a fast read. Each piece is a standalone

image obviously, yet they are in this context of a book, a body, a collection of photographs. Why do I point the camera where I point it? It has everything

to do with what happened in that place, 30 years ago, that day, what might occur, and what will never occur.

The book currently exists as a limited edition of 20 editioned artist books, self produced, printed and bound with hard covers. I am currently in the hopes of finding the right publisher for the work.

Well I guess that brings me to your Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, how do you think it has changed your work and practice? Has it changed how people view your work?

I don’t feel I work any differently or that people like me any more or less. If anything it has just opened up a lot of doors for me and allowed for my work to develop

further.

Well I know it is very prestigious, can you speak to anything specifically?

I can’t speak on anything that is not in writing yet, but it definitely has opened discussions with other professionals like curators, academics and institutes. In this digital, instagram-saturated world it is hard to get lost in the sea if no one knows what it is you are making or working on. I think of it like sports, you have to win some tournaments, play on all the fields, win some – lose some before anyone will take you seriously. Dedication is truth. I am honored that I have the support that I do from the Guggenheim Fellowship.

What do you think of instagram? Do you have an account?

You know what I don’t have one actually. I think it’s great though. A lot of photographers will say that they hate it and it makes it more challenging to separate them. I think it’s great though that anyone can pick up a camera or video camera and shoot anything. It’s not like I put a ton of copyright stuff all over my work. I mean, why be so pretentious or protective of something that is intended to share?

(laughs) A bit idealistic I guess.

We agree, thank you Karolina.

Karolina Karlic is living and working in Los Angeles. She is currently working on a new project that is focused around the North Dakota oil boom. See more of her work at karolinakarlic.com

For book inquiries, contact Karolina directly. Each book comes with a signed 8×10” print from the book.

Matt Szal is artist/art historian from Fort Worth, Texas.