William Glaser is a photographer based in Minneapolis, who just recently joined Aint-Bad as an Assistant Editor and Writer. While William enjoys a wide range of photographic interpretations, his own photographs celebrate regional-specific individuals and objects while exploring possible narratives. Before earning his BFA in photography at The Savannah College of Art and Design, he studied philosophy at Western State Colorado University and The University of Connecticut.

In this interview, I talked to William about his photographic pathway, the evolution of his work, and the contemporary notion of the ‘The New Document’ in relation to his most recent series, My Father, The Cowboy Actor.

Early Work

Early Work

Julia Wilson: Can you talk about the different ways you have experienced photography? How have your theories surrounding the medium evolved?

Will Glaser: I became immersed in photography as a sophomore in college at the University of Connecticut after a brief stint in philosophy at Western State Colorado University. In the beginning, I judged photography by its representation, nothing more. In other words, the “beauty” and subject matter were all that mattered. Photography seemed heroic and straightforward. Eugene Richards putting himself in these incredibly dangerous situations in Dorchester or Nan Goldin’s diary of sex and daily life in New York City…it was a simpler time [laughs]. My photographs, like my age, were underdeveloped (no pun intended) and didn’t have much to say. After I transferred to Savannah College of Art and Design, I started working for the non-profit, Deep Center, that helps show teenagers the power of writing, poetry, etc and how it can positively impact their community. I still believe in the project, the politics behind it, and the program itself, which would be an amazing opportunity for any teenager regardless of their background. I started to realize the “power” I had – whether that be selectively editing work to fit a narrative, setting up scenes, what have you. While this is something that every photographer does to some degree (we can only point our camera in one direction), it came to the forefront of my mind when I had to string together a body of work for a non-profit, as well as build relationships with the teens. Reading their journals, talking to them about their lives…it was clear that I couldn’t “capture” any of that with a camera, and to be quite honest, I don’t know many that can without being incredibly didactic or boring. It was around this time I bought a large format camera and started walking around the town, photographing my neighbors. In many ways, I was under the spell of Jeff Wall and Alec Soth.

Early Work

Early Work

D, from the project Deep

Amira, from the project Deep

Amira, from the project Deep

Tyler, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Tyler, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

After graduation, my expectations of how I thought I could work reshaped rapidly. I worked for The New York Times as a photographer (intern) and realized my heart wasn’t in photojournalism. Immediately after, I worked for Martin Schoeller, a portrait photographer in NYC, as a studio assistant intern. While I learned (almost) everything I know from these two internships, I realized I wasn’t making work I cared about nor did I want the life of a photographer in NYC. Since leaving, my interest in photography has turned inside out. I’ve gone from photographing strangers, to retreating inward and focusing on photographing my father…worlds I never thought to explore. When I do venture outward, I’m much more careful and considerate. I’d like to think I contemplate on more than just the aesthetics of subject matter now.

Sisters, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Sisters, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Date, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Date, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

JW: To continue your thoughts on photojournalism and the impossibility for photography to ever truly embody experience – I’d like to talk about the idea of the staged or fabricated image. How do you feel about the contemporary notion of ‘The New Document’ – something falling between fact and fiction, exposing a greater ‘truth’ beyond bare documentation in the strictest sense?

WG: I aspire to have a position in this in-between. I was constantly torn between these two worlds, fact and fiction, and where photography lived in that spectrum until I eventually accepted Tod Papageorge’s theory that all photographs should be viewed as fictitious in the nature of their being. After reading his book of essays, “Core Curriculum,” I can honestly say I felt liberated from our cultural expectations of what a photograph should do. While some of my photojournalist friends might find this claim to be in the spirit of this post-truth paradigm we’re living in, my most successful photographs, and the work I’m constantly seeking out, is ambiguous, ambitious, and ‘breaks’ the mechanics of the camera. While the every day can spontaneously generate scenarios that we could never begin to imagine, I believe the Photographer, or Director in this case, should be able to move, manipulate, and alter the scene.

Savannah Bible Rehab Center Cafeteria, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Savannah Bible Rehab Center Cafeteria, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

JW: Outside of a photojournalistic setting, do you believe that the photographer owes it to the viewer to present staged or intentionally fabricated work within that context?

WG: When you go to a movie theater, you know you’re watching roughly 120 minutes cut and edited from hundreds of hours of footage…Yet we all get excited, angry, upset, etc. when these scenes unfold before us. Do we care that it’s just light on a screen and actors paid to perform? We purposely suspend our notion of reality and place. Now, how does that compare when the Coen Brothers state in the beginning of Fargo, “This is a true story”? Do we take the Director(s) at their word? How does that change our perception of the story? As soon as you bring these words and concepts like truth and deception to the table, you’re playing a different game. Photojournalists are always walking a tightrope [and not many can handle that burden of responsibility], but not acknowledging that the nature of photography is a fractured moment, similar to a movie frame, is dangerous and immature. All photography discloses and conceals, and shouldn’t be taken at face value.

Ray, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

Ray, from the series As I Venture Toward The Sun

JW: As I understand, for your most recent and ongoing project, My Father, The Cowboy Actor, you lived with and photographed your father in Flagstaff, AZ for about two months. Did your approach to photography shift when photographing something so isolated and close to yourself?

WG: I go into most projects with a list of sorts: objects, motions, interactions, scenes…it’s a kind of preparation that you might consider before you start a shoot, or a storyboard for a film script. However, this project is like none other I’ve done before, nor did I want to just photograph my Father continuously. I decided to put the camera away for the first few days, and ended up photographing heavily during the second half of the month. Often this was recreating, staging, or anticipating a moment that would occur everyday at a certain time, whether that be Charles (my father) slowly sauntering out of bed, cigars in the evening, or our afternoon hikes. I’m not a Photojournalist; I’m an Artist using photography as a means to an end…and this end is one that’s purely selfish: to make an object of my Father and spend time with him. In essence, the photographs are a document of this event that would occur whether or not I was present, so like many photographers utilizing a documentary style, it’s a world betwixt and between several styles of working. How “real” or “true” the photographs are is irrelevant.

Charles, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Charles, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

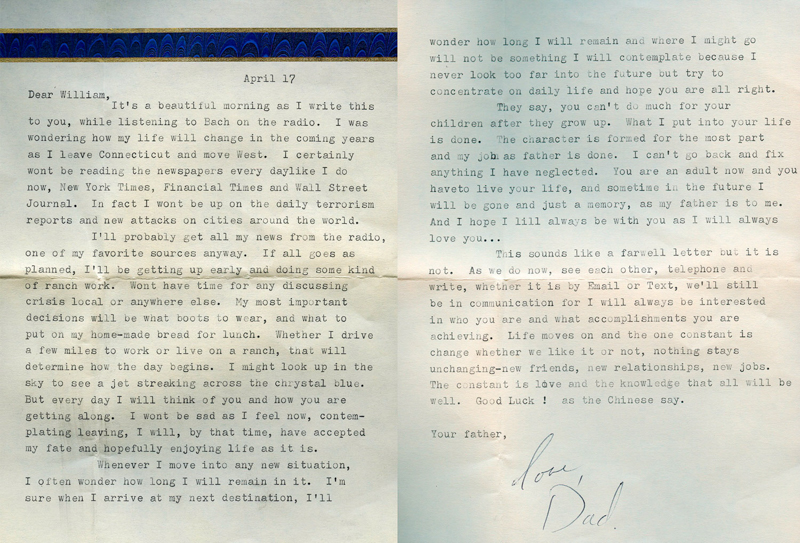

Letter from April, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Letter from April, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

The Town, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

The Town, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Getting Up, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Getting Up, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Surveying the Barn, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

Surveying the Barn, from the series My Father, The Cowboy Actor

To view more of William Glaser’s work please visit his website.