In Conversation with Parker Hill

Parker is an NYC based writer/director who graduated from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Her thesis film, ONE GOOD PITCH, premiered at the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival. Her latest narrative short film HOMING IN (BFI London Film Festival 2017) was screened as MoMA and released on Short of the Week. Her short documentary SANDERSON TO BRACKETTVILLE was released as a Vimeo Staff Pick. Parker is also a published photographer whose work has been featured in several magazines including Kodak’s podcast The Kodakery. Her first photo book, The Doctor’s House, was released by Riot Time in 2018. Parker is currently in post-production on a feature documentary and editing a companion photo series about a group of teenage girls from Texas.

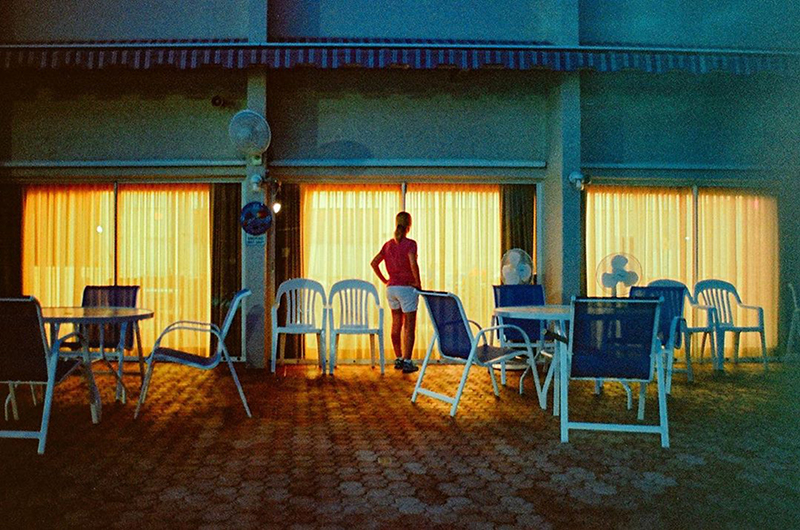

The images are from various photo series by Parker.

MK: When did you start photographing? What were some of the first things you photographed?

PH: A friend of mine showed me Todd Hido’s, House Hunting. So for the first 6 months of making photographs, I almost exclusively shot houses at night. I would drive around the suburbs, I was just obsessed with it. This was November 2015 when I started.

MK: The relationship between your photography and your film, it feels like Homing In was very in line with sort of vision you have photographically. But as artistic media, they’re quite different. They can work towards very different ends. Do you feel like you’re the same artist when you’re making a film and when you photograph? Is the creative satisfaction the same?

PH: When I think about Homing In, a short film I made that was so largely inspired by the series of houses at night I was shooting, absolutely. The same artist made both. At that time, I shot two photo series and made films about both, so taking photos was connected to my interest in filmmaking. The processes for the photos and the film were so different, obviously one is like this meditative hours alone of driving around the suburbs looking for houses, and one is hours spent with a crew of 20 making a film and needing to articulate and express my vision to many people. But I was completely after the same thing with those projects, especially because they were both shot on film. Homing In was so early in my journey as a director. Once I discovered photography, honestly, I was just so focused on the visuals and putting my stamp on that film. I was admittedly perhaps more focused on creating a visual atmosphere more than the story for that film, but I’m proud of it. I made it at a time when I was so insecure about my voice as a filmmaker, that I wanted so badly for the film to look like I, and no one else, directed it. I learned a lot in the process of making Homing In and I’m still learning, and short films are a great space to try things out.

Now that it’s been a few years and I’ve been photographing completely separate from films I’m making, the two have started to mean different things for me. My initial interest in photography was I think, in part, an emotional confidence booster about myself as a film director. Now the two coexist and intersect, but I’m starting to realize that there are certain projects that I’m only interested in as a photo series. I’m starting to learn that there are moments I see that succeed much better as still image, and some moments that succeed more for Motion Picture. I’m currently co-directing a feature documentary and shooting a companion photo book with the film, and it’s been pretty awesome to have captured the same moments for the film and the photograph, and getting to see which works better: either because the moving film has a temporal or rhythmic element or maybe the still frame is just more question-begging.

MK: So you had said a word earlier: atmosphere, That must play a big role in your decision to use analog film. Your subject matter often deals with antiquity and nostalgia and abandoned objects and suburbia. What draws you to that?

PH: I’m not exactly sure there’s one thing that draws me to older things. Maybe some of it has to do with my family history and growing up hearing stories about my moms family and their community up in the Catskills, New York. She grew up a part of this whole world of the Catskills, and I’ve seen so many pictures and heard story after story about what it was like in the 60s and 70s. From famous comedians performing up there, to athletes training, to 4th of July bathing suit contests, that whole resort hotel world has just always been a part of my life, even though it ended before I was old enough to see it. So I think I just associate some of these older things (the color palette, the textures, wallpapers) with the glory days of the Catskills and maybe I’m fascinated for a world or community that I’m never quite going to be a part of. Maybe it’s because I don’t really feel part of a community right now, so I’m yearning for these older times. I’m not sure. I do think I was interested in the American suburb because I never lived there. I like old things because I’m not really sure what my things are. I don’t know Marc!

MK: As a filmmaker, you’re expected to come to your work with very clear ideas and well-articulated plans because as a medium, it requires so much cost, an army of people to whom you must communicate your vision. In photography, you can step back and not have to intellectualize it so much in the process of making. You can use it as a way of revealing more to yourself about what your intentions are.

PH: Absolutely. Photography has kind of taught me what I’m interested in. I’ve been compelled to shoot stuff, then afterward I’m like oh I guess I’m fascinated with something here. Unlike filmmaking, the barrier to entry is much lower with photography, not only with a crew, money, and planning but also with the perfect idea. Photography allows more freedom for me, I don’t have to know why I want to shoot something but I can just be compelled, and think/regroup and reflect afterward. I feel like I don’t have to defend my interest or my ideas as much, compared to filmmaking at least. I can just go and make the thing and then let it speak for itself and people get it. I also love that photography allows for a process of refining that filmmaking doesn’t. I can go and shoot, look at the pictures, learn from them, and then go back out and shoot differently. It’s just a different process of creativity. When making a short film, spending all this money, with a 25 person crew, you have this pressure to get everything you need in like 2 or 3 days. Yes, you can refine the film in the edit, but the filming often doesn’t allow you to learn from your footage and try again on the same project.

The relationship between photographer-me and film director-me is going to keep growing. It’s not that one process is better or worse than the other, it’s that certain products can come out of one and certain products can come out of the other.

MK: Being someone so concerned with the visual, is collaborating with another artist giving them some of the artistic license? Do you feel like you’re losing any ownership over your work when you collaborate with a Cinematographer? Or has it been nice to have another head in it with you?

PH: I mean, in general, as a director, I’m still growing. It’s been a process (and I’m still getting better at the process) of letting go. I think for a while I was directing from a place of insecurity, working with talented people that had made far more work than me, so I was so concerned about my voice not being at the forefront of the work. What that means in terms of letting go is being a little relentless about how I want the work to look. I’ve been told I’m specific… But in all honesty, with the more I’ve made, the less worried I am about making sure my voice will be recognizable. It’s going to happen, so I should probably worry more about the story and overall vision for a project than almost purely focusing on the cinematography. Now, I think about working with a cinematographer more as a challenge for true collaboration. I know what it would look like if I took a photo of the scene, but what would it look like if we (me and a DP) shot this together? I think it’s an exciting challenge to try and figure that second one out because it forces you to go beyond your initial instinct and create together. I don’t want a DP to be a conduit for how I would shoot something, rather how can I use their set of tools and my set of tools to be fruitful together?

MK: Why did you never want to become a cinematographer?

PH: I didn’t even know I was interested in this until after film school! Two things I would say to that question, One: I became very good friends with a cinematographer, he introduced me to photography and it clicked, but I don’t know, I feel like if I became very good friends with a writer I would have two feature scripts finished by now. Two: taking pictures is easier than f-ing writing. The real homework for me is writing. The day I picked up a 35mm camera is the day I closed Final Draft on my computer for a few months. It doesn’t mean I should be a DP, it means I should do my homework!

MK: You made a film about Jason Lee making work for his series and book, A Plain View. Did the experience of seeing him work influence your practice?

PH: Seeing Jason photograph definitely made an impression on me. At that time, I hadn’t even been to the state of Texas yet, I hadn’t been on cross country trips yet. Which now, that landscape is such a huge part of my work. So it was exciting to just get to be on the road down there, and try and capture this America I wanted to see. We were with him for the West Texas leg of his book, so very desolate, almost frozen in time.

I had been following Jason on Instagram and he was writing about the work he was shooting with A Plain View and I reached out. He introduced me to 4×5 and large format photography. He took me to his printer, where he makes these like 4 by 5-foot prints of his work and it just woke me up to this whole other side of picture taking: shooting to print. It woke me up. I’m an analog photographer, working pretty much exclusively on film. I realized the way I wanted my images to look, or the tendencies I’d have for color were so specific to the one lab I had been using; the one scanner at that one lab, and it just kind of blew my mind that I was exposing based on the scans of the lab I used. It just woke me up in terms of a whole other way to shoot and shooting to print. Is this a worthy image? Does this need to be printed? Is printing this photo the best way to look at that photo? When I started taking pictures I posted them on Instagram. The whole Jason adventure was a wake-up call: I gotta make books. I gotta print these pictures.

MK: Does it make you sad that many more people see your work on Instagram rather than in print?

PH: No, it doesn’t make me sad. They’re only seeing that work that’s for Instagram. I’m increasingly viewing it as separate works: photos for print and photos for ‘the gram’. I shoot a ton and I post a ton, but with this new project, we’re not posting anything from the book until we’re near launch. So anything I’m posting aren’t the selects, they’re not even related to the selects. I just view them as different forums.

MK: You had mentioned before how Jason introduced you to 4×5 film. Many of your photos are shot on 35mm. But recently, you’ve been shooting with medium format and 4×5. What does film bring to the table that digital can’t? Has working with larger film formats changed your working process or the photos you take?

PH: As far as film, I’m just an analog person all the way. When I started taking pictures I was making them on film, so it’s the same for me, my interest in photography and film. With the recent project I’m working on, there are light constraints, so this one has been half digital and half film. It’s been an interesting process because once I have a digital camera in my hand I’m like snap snap snap, and I have to go through 2000 photos instead of 200. But it’s working for this project, following subjects that largely exist at night, so it works for us. But I just like what film offers: everything from your attention, your focus, to the mistakes, flares, the colors! There are images you just can’t get digitally, and that’s exciting. Jason got me into shooting more medium and large format. It’s a different way of shooting, shooting to print. The exposures per roll have changed what I shoot as well, you have to be even more discerning than on 35mm. I like that.

MK: Riot Time is about to release a book of yours that contains a lot of archival material. Can you speak to selecting and sequencing photographs that are not your own?

PH: It was thrilling, going through someone else’s archive felt like hunting. A similar feeling is when I’m on the road and hunting for a photo. I mean, the book is made up of my stepfather’s late father’s photos. I went to photograph his mom’s house and she was moving and I discovered a bunch of these slides. I went home and scanned a couple and just so happens that the first five or ten I scanned were amazing. It was like mining for gold. It was almost as exciting as shooting. The more I looked, the more I started to understand. It was a process of learning what this guy was interested in, what his tastes were. I never met him, but I know what he looked at.

MK: Do you feel analog film connected you two?

PH: Absolutely. He was shooting in the 60’s and 70’s on Kodachrome and Ektachrome slide film. He shot on film stock I can’t shoot on anymore. He captured colors I can’t capture, not only because of the Kodachrome chemistry being gone but also cars were painted different colors back then, people dressed differently. The color palette of his time is gone. I felt connected because I scanned them; because I have this personal experience of literally digging and holding them up and being like, “Oh my gosh, I can’t wait to see what this one looks like!” Even though I didn’t author any of the images it felt like I got to participate. There was still a pride of authorship, I mean I selected the photos. But if five other editors worked with these photos, it would be five different books.

MK: Are there any photo books you’ve been returning to for inspiration recently?

PH: For the series that I’m currently working on I’ve just been searching for the middle ground between staged and not staged; photos of girlhood. So I’ve been looking a lot at Melissa Ann Pinney’s Regarding Emma, Lauren Greenfield’s Girl Culture, and Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures. I recently discovered this exhibition called Another Girl Another Planet, it was organized by Gregory Crewdson in 1999, featuring 13 female photographers from Kurland to Malarie Marder. So much good stuff in there, big recommend!

To view more of Parker Hill’s work please visit their website.